A colleague just argued that “karate” came from the Pēchin class of Okinawa. I think this is a oversimplification, and it is also one of those stories based on guesswork and premature conclusions.

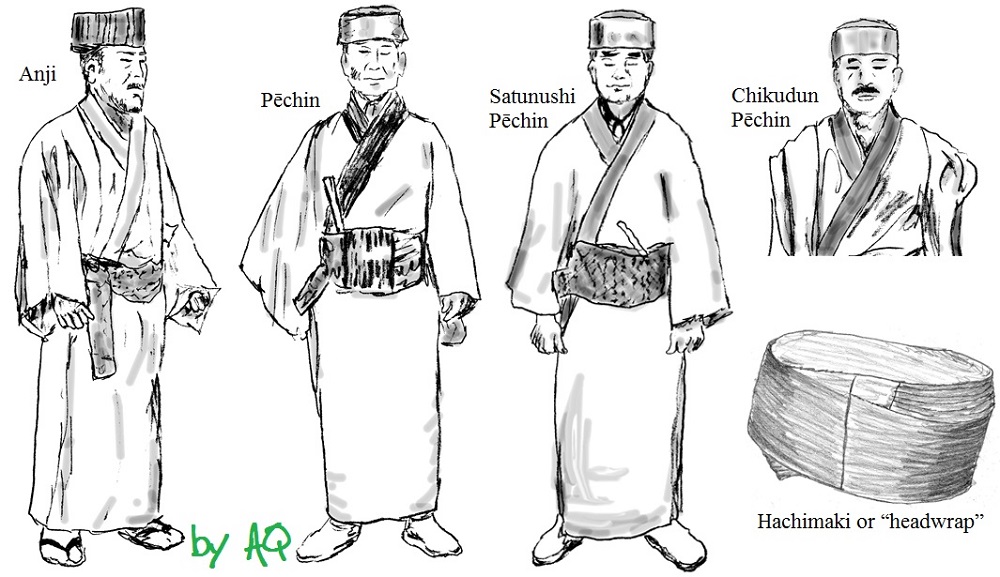

According to censuses of 1873 and 1880 there were 296 households of Pēchin class at that time, and 20,759 households of Satonushi Pēchin and Chikudun Pēchin class. That’s a total of 21,055 households at one time around the mid-1870s which you could count among a “Pēchin class.”

How many “Pēchin-ranked” persons do you know who taught karate?

How many percent of the total of 21,055 households is that?

Do these numbers provide you with a statistically meaningful value that supports the conclusion that “karate was handed down by the Pēchin class”?

Of course not. Rather, the existing data of the “martial arts Pēchin” are obviously outliers on the extreme boundaries of a Gaussian curve.

As a side note, one characteristic of the royal administration of Ryukyū kingdom was to promote as many people as possible to rank. This at least is something that is traditionally found in modern karate as well. However the claim that karate came from the Pēchin class is difficult to prove.

So how many Pechin taught martial art? Let’s calculate! And while doing so, let’s add the primary sources and their year of publication to the data set.

Next, it should be noted that from among nine ranks, the Pechin class occupied minor rank 7 through to major rank 3, which is a huge field. If someone did martial arts was more related to the actual duty they held, and probably to personal preferences.

Well, there are various martial arts techniques that are decidedly NOT from the Pechin class. For instance, in Matayoshi Kobudo, there is Jitodee-mochi. This refers to a s-called Jitodai, a rural official who was not among those who held any court rank, Pechin or else.

Chinen Sanra (Yamanni)? Nope. He is also known as Chinen Usume already in the 1910s, with Usume referring to an older person from the class commoners.

Kinjo Ufuchiku? Nope, commoner.

Sakugawa Kanga? Well, even if this legendary warrior of an early 20th century theater play actually existed, Sakugawa no Kon and Shirotaru no Kon was handed down among commoners (Tawada 1973). They were probably folk heros.

How about Itosu? Well, yes, he held a court rank, but the “karate” handed down by him was newly created around the beginning of the 20th century, transformed as a physical education meant to drill young men in preparation for conscription and probably had little in common with the rural dances that Funakoshi referred to as “not-yet developed karate,” which argumentum e contrario means that karate – at least partially – is “rural dances further developed.” And rural people were not of Pechin rank.

I did an Ngram search, which shows when phrases have occurred in a corpus of books. The term Pechin in karate context apeared only with the popular books of Mark B. and Patrick M., so rather recently and in the larger context of retrospective karate invention, and from there radiated outward to other publications and websites.

In the Okinawan karate circles similar examples are found, such as can be seen in Taira Shinken’s phantastic story of Hama Higa Pechin, which is another example of the old tradition of mixing martial art references into actual historical events, of which there are numerous examples, mostly from the 1950s and onward. One of the most representative is the postwar story of Sakugawa and Matsumura, in which a ordinary meridian chart was sold as an atemi chart handed down from legendary Sakugawa to half-legendary Matsumura.

© 2022, Andreas Quast. All rights reserved.