Yesterday, I received note about a rare bō kata of Okinawa. It is almost unknown in both name and technique, let alone its history. Almost.

Names

The name of the kata is Kuwae no Kon, and it is also known as Torisashi Umē no Kon. Let’s take a look at the names one after the other. Kuwae is an Okinawan family name. The suffixed phrase “no kon” is the phrase regularly used for almost all Okinawan bō kata, with only a few exceptions to this rule. Torisashi refers to catching birds using a birdlime-covered pole, or otherwise to the birdcatcher himself. Finally, Umē was used to address the member of a noble family.

From the above it can be said that Kuwae no Kon means “The bō techniques of Kuwae,” and Torisashi Umē no Kon means “The bō techniques of His Excellency, the birdcatcher.”

Tradition

In the Okinawa Karate Kobudō Encyclopedia (2008), no information is found about Kuwae no Kon or Torisashi Umē no Kon. However, the following information exists. However, the following information exists from a Japanese book. The page was shared by Walt Young.

Kuwae no Kon (a.k.a. Torisashi Umē no Kon)

Kuwae was a master of bōjutsu to the extent that he could thrust flying birds, so it is said that the people were in awe of him, calling him Birdcatcher Umē (Umē was an affectionate nickname for a warrior [bushi]).

Path of Tradition

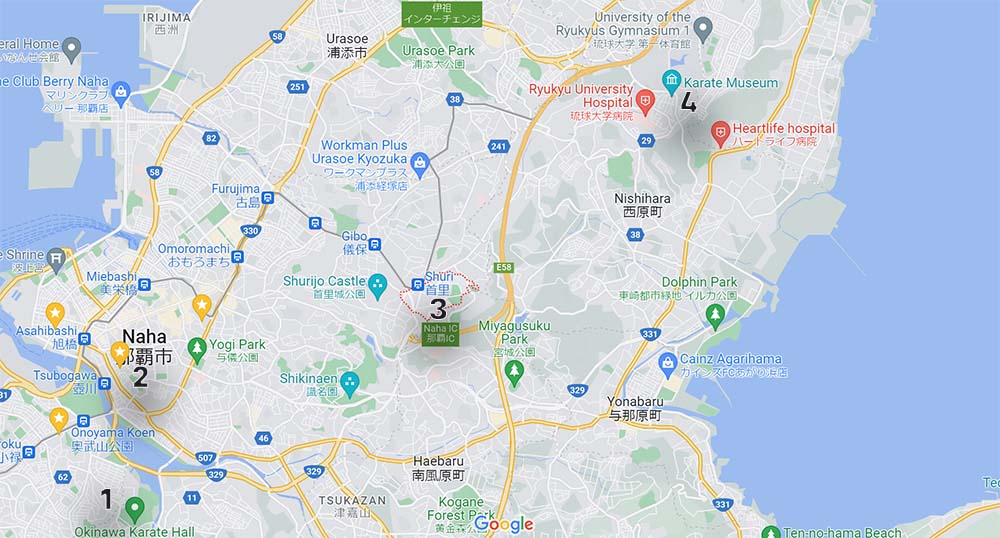

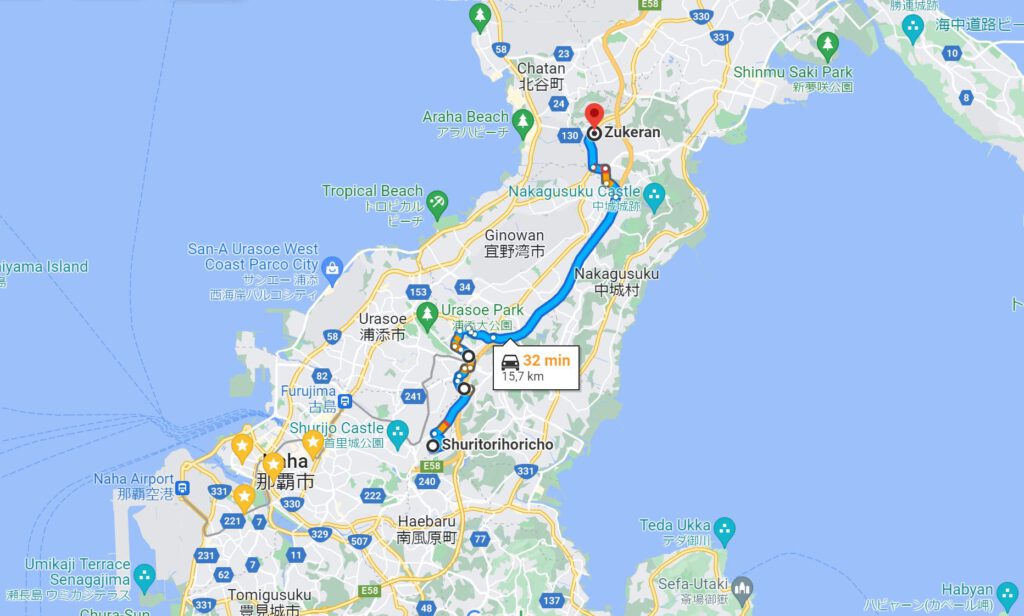

- Umē-gwā, the second son of the Kuwae Dunchi from Shuri Torihori

- → Zukeran village section in Kitanakagusuku (Yogi Seikō, Nakasone Chōho)

- → Ōshiro Seira (instructed by Yogi Seikō in 1928)

- → Kina Masanobu

According to the above, Umē-gwā was the nickname of the second son of the Kuwae Dunchi from Shuri Torihori. ,

From this Umē-gwā, the bō techniques reached Yogi Seikō and Nakasone Chōho in the Zukeran village section of Kitanakagusuku.

Then, in 1928, Yogi Seikō taught the bō techniques to Ōshiro Seira, from where it reached Kina Masanobu.

Performances of the Kata

Let’s take a look at the performance of the kata. The first video is a performance by Kina Masanobu. who is mentioned in the above description of the tradition. While unrelated to this bō kata, Masanobu Kina is also the nephew of Kina Shōsei, who is known as a master of saijutsu in the tradition of Kinjō Ufuchiku.

Note that the movie starts with the bō on the left-side of the body. Then the film color changes and the bō position changes to right handed. At the end the kata ends with the bō on the right side. Then the film color changes again, and the bō is on the left side again. In short, at the beginning and at the end, there were other parts inserted into the movie. Don’t get confused by this.

Another performance is by Robert Teller Sensei, who had learned the kata from Kina Masanobu. You can watch it here.

The hand change

https://youtu.be/uY05psKhX4A?t=83While there are many details that could be pointed out about the techniques of this kata, there is a signature technique characteristic of this kata which is rather unique in its context. The method of this hand change itself however is also found in Chōun no Kon and Chatan Yara no Kon of Taira lineage, as well as Soeishi no Kon of Matayoshi lineage in a slightly different fashion and context.

Here’s how its done (in principle). This might have even provided the name for the kata, or it might be a hint of the special technique utilized by Kuwae to catch birds in flight, namely to place the bō on the forearm to create a stable aiming and launching device. (For animal welfare reasons, and for reasons of law, I strongly discourage anyone from attempting such a technique on live birds).

It should be noted that such stories are found elsewhere in martial arts, such as that of Sasaki Kojirō, who is said to have developed a technique of killing a bird in mid-flight (called tsubame-gaeshi). However, Sasaki himself might have been a fictional character.

Breakdown of Techniques

I have written down the individual techniques of the kata as good as possible. The number of techniques largely depends on how and what you count. In this simple assessment here, there are 37 techniques, however, it is a simplified counting.

| Nr. | Technique | Stance | Notes |

| Standing bow | Musubi-dachi | Stand straight, bō at the right side of the body. Bow. | |

| Starting position | Musubi-dachi | Raise bō slightly with the right hand and grab it with the left hand, with the left forearm in front and above of the forehead. | |

| 1 | Middle block | Right forward stance | From Musubi-dachi, step back with the left foot. |

| 2 | Middle posture | Right Nekoashi | With the bō as it is, place your right foot 45° to the left, and assume the middle posture towards the left front at 45° |

| 3 | Front strike | Left forward stance | Change the grip, place the right foot a little to the right, and step forward with the left foot. |

| 4 | Low block | Left forward stance | With the stance as it is. |

| 5 | Front strike | Left forward stance | With the stance as it is. |

| 6 | Middle block | Left forward stance | With the stance as it is. |

| 7 | Nuki-zuki | Left forward stance | With the stance as it is. |

| 8 | Low block (rear hand) | Left forward stance | Prepare a little, slide a little forward with a low block with the rear hand. |

| 9 | Front strike | Right forward stance | Change the grip, and step forward with the right foot. |

| 10 | Low block | Right forward stance | With the stance as it is. |

| 11 | Front strike | Right forward stance | With the stance as it is. |

| 12 | Middle block | Right forward stance | With the stance as it is. |

| 13 | Nuki-zuki | Right forward stance | With the stance as it is. |

| 14 | Front strike | Left forward stance | Change the grip, and step forward with the left foot. |

| 15 | Front strike | Right forward stance | Change the grip, and step forward with the right foot. |

| 16 | Front strike | Right forward stance | Look over your left shoulder, turn around 180° counterclockwise, step forward with the right foot, and strike to the front. |

| 17 | Front strike | Left forward stance | Change the grip, and step forward with the left foot. |

| 18 | Front strike | Right forward stance | Change the grip, and step forward with the right foot. |

| 19 | Front strike | Left forward stance | Change the grip, and step forward with the left foot. |

| 20 | Low block | Left forward stance | With the stance as it is. |

| 21 | Front strike | Left forward stance | With the stance as it is. |

| 22 | Middle block | Left forward stance | With the stance as it is. |

| 23 | Nuki-zuki | Left forward stance | With the stance as it is. |

| 24 | Low front strike | Right forward stance | Change the grip, and step forward with the right foot. |

| 25 | Front strike (right side) | Musubi-dachi | Look over your left shoulder, turn around 180° counterclockwise, pull back the left foot to the right foot, and strike down to upper level on your right side. |

| 26 | Sliding thrust | Nekoashi (sort of) | Loosen left hand, place left forearm and hand horizontally in front of your body to support the bō, step forward with left foot, and thrust to the front, suing the left hand as a support. |

| 27 | Front strike | Right forward stance | Rotate bō backwards, let go right hand, catch with left hand, add right hand, shuffle feet and place right forward, and strike to the front. |

| 28 | Low block | Right forward stance | With the stance as it is. |

| 29 | Low block kamae | Tai-sabaki | Quick shuffle of right foot back to left foot, left foot back. |

| 30 | Front strike | Right forward stance | With the stance as it is. |

| 31 | Middle block | Right forward stance | With the stance as it is. |

| 32 | Nuki-zuki | Right forward stance | With the stance as it is. |

| 33 | Front strike | Left forward stance | Change the grip, and step forward with the left foot. |

| 34 | Front strike | Right forward stance | Change the grip, and step forward with the right foot. |

| 35 | sliding thrust to lower level | Shiko | Look over your left shoulder, turn around 180° counterclockwise, slide forward in shiko and perform a sliding thrust to the lower level |

| 36 | Thrust to upper level | Right forward stance | Step forward with the right foot. |

| 37 | Yōi no kamae | Left forward stance | Turn around 180° counterclockwise, and assume Yōi no kamae. |

| Yōi no kamae | Musubi | Pull right foot forward into Musubi-dachi. | |

| End | Musubi | Place left arm at the left side of the body. | |

| Standing bow | Musubi |

Dunchi

The Kuwae Dunchi might be the same family as that of Kuwae Ryōsei (1856–1926), who was a disciple of Matsumura Sōkon. According to Okinawa Karate Kobudō Jiten (2008), Kuwae Ryōsei was born in Shuri Torihori, the same place mentioned in case of “Umē-gwā, the second son of the Kuwae Dunchi from Shuri Torihori.” Therefore, there might have been a family relation between them.

Dunchi is an honorific title referring to the families of Uēkata rank who hold the position of Estate Steward General (sō-jitō) among the Ryūkyū samurē. In a broader sense, it is also used for the families of Assistant Estate Stewards (waki-jitō). In the hierarchy positioned under the Udun, which belong to royalty, the Dunchi are families of high social standing. Together with the Udun, this social stratum was called Udun-dunchi. In reference to their jurisdiction over a territory under the royal government administration, they were also called daimyō-gata.

The tradition of this kata states that Umē was an affectionate nickname for a warrior (bushi), so it doesn’t seem to abide to the naming standards of Udun and Dunchi families. In short, in this case, it Umē was not used to designate a member of royalty. It should be noted that rural commoners might not have known these naming conventions and so Umē might have simply been used to show a particular respect.

The context of how this tradition took place is also unknown, but it might have been related to an administrative relation between Kuwae Dunchi and Zukeran village section in Kitanakagusuku from the times of the Ryūkyū Kingdom. In order to figure out family relations as well as territorial relations, I have looked up the genealogies of Shuri (in: Okinawa no Rekishi Jōhō [Historical Information on Okinawa], Vol. 5 Shuri-kei kafu). Unfortunately, the Kuwae family does not have an individual entry. Therefore, I couldn’t verify whether Zukeran village section in Kitanakagusuku was an administrative territory of the Kuwae Dunchi.

The tradition might also have been related to traditional village events, or to activities of the Young Men’s Corps, or to coincidence. In any case, these are just guesses and nothing is known for sure except that the tradition states that Yogi Seikō and Nakasone Chōho learned it. Since Yogi Seikō taught it to Ōshiro Seira in 1928, Yogi himself might have learned it anytime from the second part of the 19th century to the early 20th century.

Moreover, although the tradition states the Kuwae Dunchi as the origin, and uses a name related to royalty (Umē) for the protagonist, the family registers of Okinawa (Uji-shū) also show other Kuwae families from Shuri which were not of the Dunchi class, but lower samurē. In short, the person Umē-gwā might have actually been from the Kuwae Dunchi, or not.

As is typical for Okinawan martial arts, there is no source and no date for the information, and it is probably oral tradition written down at a later point in time. It is unknown by whom and when the story of the kata was handed down, and how the persons obtained the information. In the end, in Okinawa karate, most traditions enjoy the benefit of the doubt, which renders any tradition at least possible.

I hope that more study will be done on the tradition of this kata in the future and to verify more details on the persons involved.

Other usages of Torisashi

I would like to note here that the Motobu Udundī uses a torisashi, or bird catching stick, as a weapon. For instance, it is used against naginata. It is interesting to note that Motobu Chōyū was nicknamed Umē and was the person who handed down Motobu Udundī.

It is a mere coincidence and I know nothing about the technique, but my small practice bamboo actually in size and all looks like the torisashi as used in Motobu Udundī.

© 2022, Andreas Quast. All rights reserved.