Dear Ryukyu Bugei community,

As I reflect on the journey we’ve shared since the inception of this blog in March 2011, I am filled with gratitude and pride. Over the past thirteen years, Ryukyu Bugei has grown into a vibrant platform, where I’ve had the pleasure of sharing nearly 800 articles on the rich techniques and culture of Okinawan Karate and Kobudo. Together, we’ve reached and connected with martial arts enthusiasts from all corners of the globe.

Your engagement, whether through reading, liking, sharing, or commenting, has been the lifeblood of this blog. Each interaction has fueled my passion and dedication to bringing you high-quality research and the latest updates on Okinawan martial arts. It has truly been an incredible ride, and I am deeply thankful for your unwavering support.

As we embrace change and move forward, I am excited to announce that Ryukyu Bugei will be transitioning on Patreon. This move will allow me to continue offering you top-notch content in a more interactive and rewarding environment. On Patreon, I will be able to engage more directly with you, my loyal supporters, and provide exclusive content, in-depth research, and the latest news on Okinawan martial arts.

I invite you to join me on this new platform. By becoming a patron or member, you will gain access to a wealth of new content and have the opportunity to support the continuation of our shared passion for Okinawan martial arts. Your support will help sustain my work and ensure that Ryukyu Bugei continues to thrive.

Thank you for being part of this incredible journey. I look forward to welcoming you on Patreon, where together, we will explore new horizons and continue to celebrate the rich heritage of Okinawan martial arts.

Happy trails and see you on Patreon!

Warm regards,

Andreas

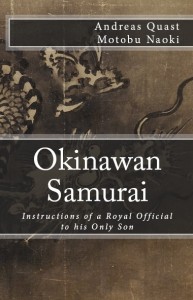

Troubled about the future of his only son and heir, a royal government official of the Ryukyu Kingdom wrote down his ‘Instructions’ as a code of practice for all affairs. Written in flowing, elegant Japanese, he refers to a wide spectrum of artistic accomplishments that the royal government officials were ought to study in those days, such as court etiquette, literature and poetry, music, calligraphy, the tea ceremony and so on.

Troubled about the future of his only son and heir, a royal government official of the Ryukyu Kingdom wrote down his ‘Instructions’ as a code of practice for all affairs. Written in flowing, elegant Japanese, he refers to a wide spectrum of artistic accomplishments that the royal government officials were ought to study in those days, such as court etiquette, literature and poetry, music, calligraphy, the tea ceremony and so on.

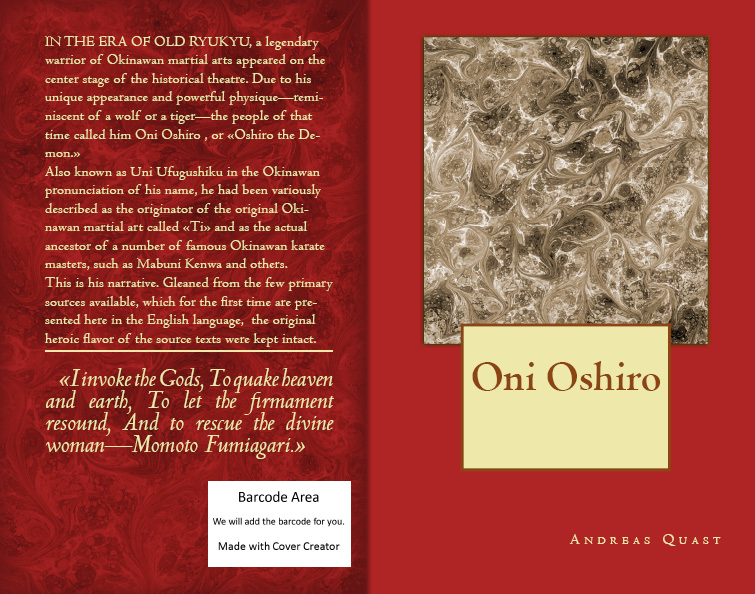

In the era of Old Ryukyu, a legendary warrior of Okinawan martial arts appeared on the center stage of the historical theatre. Due to his unique appearance and powerful physique—reminiscent of a wolf or a tiger—the people of that time called him Oni Ōshiro, or «Ōshiro the Demon.»

In the era of Old Ryukyu, a legendary warrior of Okinawan martial arts appeared on the center stage of the historical theatre. Due to his unique appearance and powerful physique—reminiscent of a wolf or a tiger—the people of that time called him Oni Ōshiro, or «Ōshiro the Demon.»