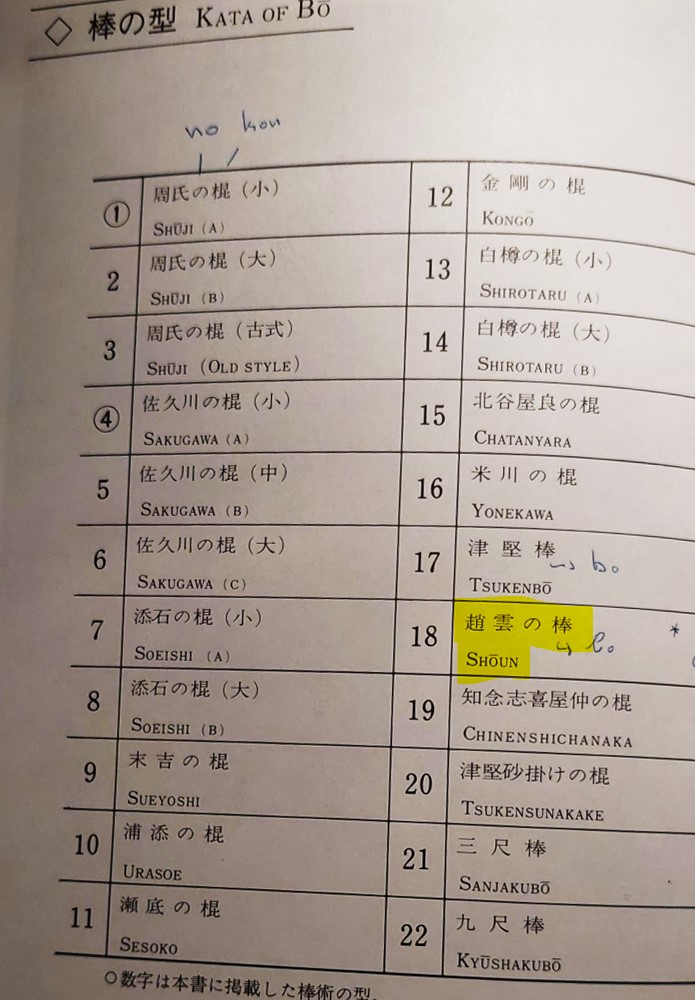

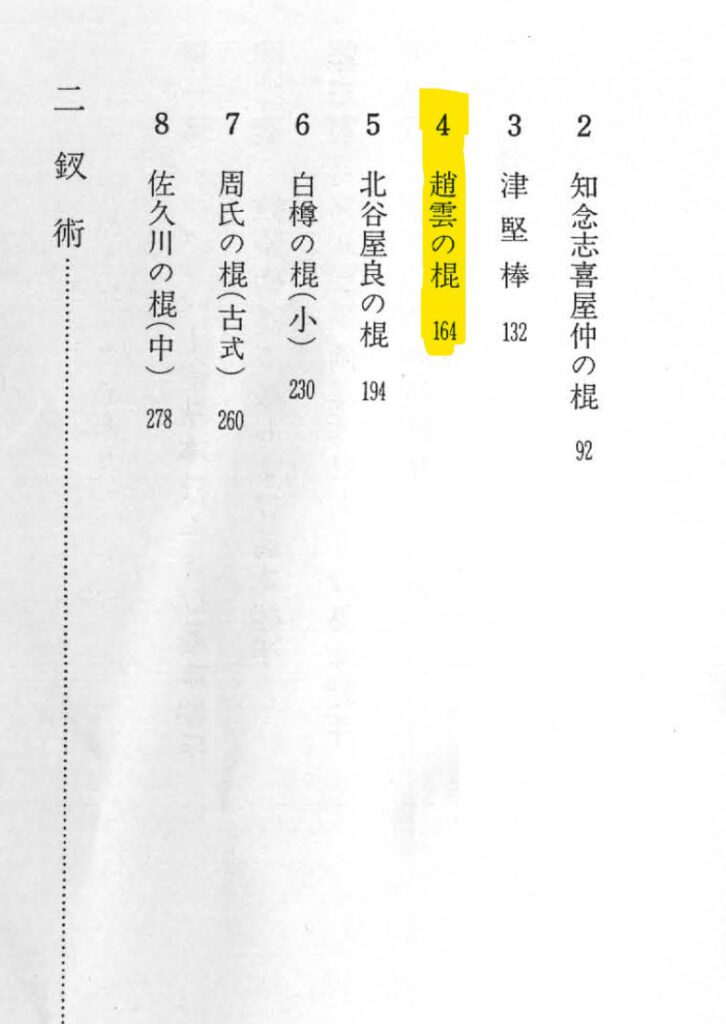

There was a discussion on social media about the spelling of a kata. In the Taira lineage, the kata is generally known as Chōun no Kon. However, in a bilangual work of 1987, there is the description of “Chōun no Bō” in Japanese characters, transcribed as “Shōun.”

For this reason, people have come to believe that the correct name of the kata is “Shōun no Bō.” This is a mistake probably made by the editor. To to time pressure and other contraints, when writing and publishing books, it is rarely the case that no typo is found in it.

There’s nothing to blame and short article is justs for those who wondered about it. First, the character Chō in question cannot be read as Shō, as can be seen in the dictionary entry below. It can be read only as Chō, Jō, or Kyō.

Second, why is it read as Chō, and not as Jō, or Kyō. This is because Chōun is a Japanese reading of a Chinese person’s name, namely that of Zhao Yun, a military general who lived in the late 2nd to early 3rd century of our time. In Japanese, his name is pronounced Chō Un, from which the kata name Chōun derives. Of course, Zhao Yun was a master of the spear.

Third, in the book above, the Japanese characters say “Chōun no Bō,” but this is a mistake as well, as can be seen in volume 3 of the compendium by the same author, which clearly says “Chōun no Kon,” and this is also the way it is written in all other schools that use this kata.

As described above, the correct name of the kata is Chōun no Kon.

Zhao Yun

Choun no Kon

By the way, this historical reference to Zhao Yun is interesting in that it uses the name of a person who lived in antiquity. It is impossible that this person handed down techniques over generations which reached Okinawa in form of this kata. Rather, using his name for the kata was obviously a historical reference by the creator in Okinawa. That is, the kata was created and named in reference to a military man of the past, whose Chinese name is Zhao Yun, which is read Chōun in Japanese, and without any actual personal transmission of techniques from that person.

This is the first example of bō kata in which it is clearly impossible to claim a personal tradition. Since it is a rare and high level kata only known by a few people, and since most people do not study very deeply, it seems that nobody ever noticed this fact. But with this being the case, it is easily imaginable and that other kata also were simple references to a historical or semi-legendary person.

How about kata such as Kūsankū? Is Kūsankū really a kata taught by a military officer by the same name who came to Okinawa in the middle of the 18th century? It is difficult to believe, and impossible to either proof or disprove.

How about Sakugawa no Kon? That Sakugawa was the “hidden warrior” of an early 20th century theater play, so again, what was first, the chicken or the egg?

In short, kata names might be historical references without an actual personal transmission of technique. Also, kata might have been created by some experts of martial choreography, just as you write a song, or develop a dance, or a theater play.

In today’s interpretations of Okinawa karate and kobudō, there is no place for such a theory. For non-Okinawans and non-Japanese, it has to be a highly effective and brutal form of self-preservation. For Okinawans, it has to be a link to their own past, a beacon in their search of identity and pride.

However this may really be, it is also true that the dōjō itself is a stage.

© 2023, Andreas Quast. All rights reserved.