Recently I wrote about the 9-foot-staff as used in Okinawan bōjutsu. While sources are scarce and fragmentary, there are a number of traditions using a 9-foot-staff. In written sources it appears first in the 1960s. However, when looking at the curricula and weapons used in extant schools, there are a few individual traditions who study the techniques of the 9-foot-staff, so it might be assumed that it has been used in the earlier 20th century. If this is the case, there might have been older traditions. The reasoning for the use of this kind of long staff is seen in the bajōbō, i.e., a fencing pole the length of a horse, or otherwise a staff of a length of ca. 3 m (OKKJ 2008: 317) and tradition has it that it was used on horseback in “the old days” (Akamine 1997).

“Never let the truth get in the way of a good story.”

― Mark Twain

So, how about actual spearmanship in Ryūkyū?

We find a clue in the written instructions by Aka Chokushiki (1721–1784), a royal official in the rank of a Pēchin in 18th century Okinawa. Aka himself has studied Jigen-ryū for many years under his teacher Kuba Pēchin Chiji. Moreover, Aka’s paternal great-grandfather Chokukō also has practiced Jigen-ryū swordmanship as well a sōjutsu (spear techniques) and naginatajutsu (halberd techniques) of the Ten-ryū, scrolls of secret traditions (densho) of which were handed down as a family heirloom.

Assuming a cautious estimate of one generation spanning approximately twenty to twenty-five years, then Aka’s great-grandfather Chokukō must have been born somewhere between 1646 and 1661. In other words, even after the Satsuma invasion of 1609, such Japanese martial arts were intermittently handed down to Ryūkyū. According to this, Japanese-style swordmanship, spear and naginata were practiced in Okinawa already during the second half of the 17th century, and handed down among certain government officials.

Still in the middle of the 18th century, minister Sai On (1682–1761) noted as follows:

“It is desirable to get all samurai instructed in the methods of the spear (yari), the glaive (naginata), and the bow and arrow.”

Naturally, the instructors for such kinds of weapons and martial arts would have been from Satsuma or otherwise would have been trained there. This matter is closely related to the Satsuma Resident Commissioner in Naha and therefore to the various liaison officials from Naha, known under names such as Omono Gusuku, Yamato Yokome, Oyōgu Atari, Okariya Mamori, etc. The methods of training used were logically and undoubtedly heavily influenced by Satsuma martial arts.

Read all about it in “Okinawan Samurai.”

As a member of a senior samurē family, Motobu Chōki had a rare insight into warrior traditions of Okinawa. In his 1932 work, Motobu mentions the spear as a martial art in Ryūkyū.

Nishinda Uēkata […] was the ancestor of today’s Nishinda in Shuri Gibo. It is said that, in addition to karate, he was also skilled with the spear.

‘Guan Yu’ Sadoyama, as his name implies, was the owner of a beautiful beard. He was said to have resembled Guan Yu of old China, who indeed looked like Sadoyama. He is said to have been skilled in karate and in addition to having been a master of the spear.

As an early modern era martial artist of the same generation as the venerable elder Itosu, Tomigusuku Uēkata was a master of the Koi-ryū. At present, his favorite disciple Izena Chōboku is still alive. Tomigusuku also distinguished himself in spearmanship and it is said that people valued his horsemanship over his karate. Particularly, with his specialty being spearmenship on horseback, when Tomigusuku mounted his marvelous 182 cm tall chestnut-colored horse and seized his spear, any enemy – how formidable he might have been – flinched.

Like this, there was spearmanship on foot, and spearmanship on horseback. It is important to note tough that in Japan as well as in Okinawa, only senior samurē family members could ride a horse. A commoner could not ride a horse.

The above should be sufficient here to establish the historicity of spearmanship in Okinawa. While various Japanese schools of spear and naginata might have been instructed in Okinawa between the 17th and 19th centuries, and while there might even have been indigenous Ryūkyūan methods, the only concrete hint is the mention of spear and naginata of the Ten-ryū.

What kind of martial art was the Ten-ryū?

As described earlier, the spearmanship (sōjutsu) and halberd/glaive (naginatajutsu) of the Ten-ryū was trained in Okinawa already in the 17th century. The Ten-ryū is the school of Saitō Denkibō (1550–1587). He is said to have been a student of Tsukahara Bokuden (1489–1571), famous for using the lid of a pot for fighting, which is a similar idea as in the tinbē of Okinawa, isn’t it?

Although the Ten-ryū included various martial arts such as sword (kenjutsu), spear (sōjutsu), halberd (naginatajutsu), chained sickle (kusarigamajutsu), staff (bōjutsu), throwing blades (shurikenjutsu), and the jūjutsu-varieties of torite and kogusoku, the contents differ according to lineage. The founder Saitō Denkibō was born in Ite in the Makabe district of Hitachi province (today’s Sakuragawa City in Ibaraki prefecture). According to legend, he first studied Shintō-ryū under Tsukahara Bokuden (1489–1571). In 1581, while Saitō Denkibō retired for prayer to the Tsurugaoka Hachiman Shrine in Kamakura, he was awarded a “scroll from heaven bearing the exquisite skills of the sword written on it,” and called his style Ten-ryū, or “School from Heaven.”

However, there are a number of different legends about this school’s establishment and its spread. Saitō’s disciple Ijichi Shigeaki handed down Ten-ryū in Ōsumi, which bordered on Satsuma and Hyuga provinces. This lineage was called Muyama Ten-ryū. It was handed down generation after generation by the Ijichi family as vassals of the Tarumizu Shimazu House, one of the four top-ranking Shimazu retainers. The Ryūkyūan embassy in Kagoshima was located close to the mansion of this Tarumizu Shimazu House. Most importantly, when looking at Ryūkyūan history, there is a large amount of persons by the name of Ijichi who were sent to Ryūkyū as officials by the Shimazu House.

The Tarumizu region was also famous for its poetry circles. These Tarumizu poetry circles were of the Asukai-ryū. Suekawa Shūzan compiled the Nami no Shitakusa, an anthology of poetry from the Tarumizu region around 1786, while living a secluded life in Tarumizu Nishiyama. Others who lived during this era was Nikaidō Yoemon Takayuki, one of the students of Hino Sukeki, as well as disciples of Karasumaru Mitsumoto and others.

Besides the Satsuma domain, during the Edo period (1603–1868) Ten-ryū was handed down to several other regions, such as the Tanba Kameyama domain, Tendai domain, Akita domain, Aizu domain, Mito domain, Hikone domain, Akō domain, and the Nakatsu domain. Schools that branched off of the Ten-ryū are Shinten-ryū, Shimazaki Shinten-ryū, Shinten-ryū, and Kako-ryū, among others.

However, from among the schools that descended from the Ten-ryū, today only the Tendō-ryū is still extant. While the instruction in Tendō-ryū is often centered on the glaive (naginatajutsu), it uses various weapons, namely swordsmanship (kenjutsu), glaive (naginata), chained sickle (kusarigama), staff (jōjutsu), short sword (kodachi), two short swords (nitō), and knife (tantō).

In short, it is impossible to know how the spear and naginata techniques of the Ten-ryū looked during the 16th to 19th century on Okinawa, and whether or not it has any resemblence to today’s 9-foot-staff as used in Okinawan bōjutsu.

To get an idea of the use of the spear in Japan during that era, you may turn to the Hōzōin-ryū sōjutsu, which was established in the 16th century. Other than the 9-foot-staff of Okinawa, the Hōzōin-ryū uses a cross-shaped spearhead (jumonji-yari) which offers a larger technical variety in application. This is expressed by the description, “a spear when thrust, a glaive when cut, and a sickle when pulled.”

As shown above, Japanese spear techniques (sōjutsu) were practiced in Okinawa in the 17th through to the 19th centuries. It may be assumed that they still existed among certain royal government officials or samurē families in the 19th century and might even have been handed down to the 20th century in individual cases. However, details of a continuation from the latter 19th to the early 20th century remain unclear.

These spear techniques were used on foot. Contrary to this, some Okinawan traditions established a connection with the spear used on horseback. While there was no real cavalry in early-modern Ryūkyū, spearmanship on horseback existed among the aristoracy, as described by Motobu Chōki. Besides, in Japan as well as in Okinawa, only senior samurē family members could ride a horse. Commoners could not ride a horse so mounted spearmanship was an exclusive and rare thing. In fact, Motobu’s note is the only one I ever came across about mounted spearmanship in Okinawa.

Another important detail is that the Okinawan 9-foot-staff is used with the right hand in front, just as in case of the 6-foot-staff. Spear techniques anywhere else in the world, as well as in ancient schools of Japanese spearmanship, are performed with the left hand forward. By researching the bilateral asymmetries in the strength of the upper limbs, anthropologists even established that Neandertals used spears with the left hand forward to thrust during hunting.

This indicates that there was probably no personal transmission and continuation from the old spear techniques to the modern 9-foot-staff.

So, how traditional is Okinawan 9-foot-staff? As is often the case in Okinawan martial arts, in theory it is possible that there was an actual personal tradition of spear techniques that became today’s 9-foot-staff. However, it is also possible that the 9-foot-staff is a retrospective historical construction, a tradition that is backdated when in fact it was re-created in the postwar era.

This certainly needs more study.

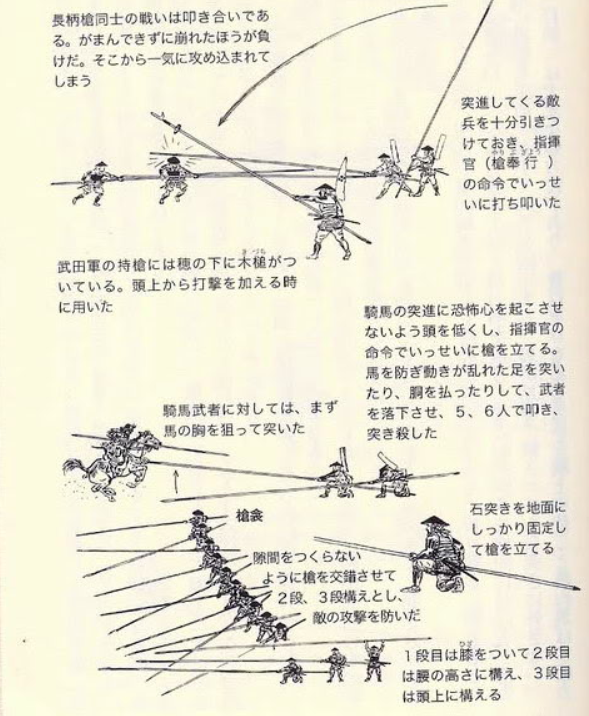

One of the more interesting techniques of Japanese spearmanship is raising the spear high vertically, and just slamming it down on the enemy.

© 2023, Andreas Quast. All rights reserved.