It was just one or two weeks ago that Mr. X asked if I knew something about a certain bō-kata, or made a movie about it etc. I immediately knew what was going on and had a guess which dōjō he referred to, but Mr. X was reluctant to confirm it officially. So, I thought, it is still a bit secret. Then I received another request yesterday from Mr. Y, about the same bō-kata, inquiring if I knew anything about it, if there were videos out there etc. pp. This time, however, Mr. Y confirmed that it was Sensei Z from Okinawa who reintroduces the kata as what might best be referred to as an “extracurricular study kata.” Sensei Z trained since the 1970s and his technique is smooth so I am sure it will become a great kata. “Extracurricular study kata” are quite hip on Okinawa, such as can be seen in Matayoshi-lineage Kobudō as well as in Taira-lineage Kobudō. The most important points to it are the following (list not exhaustive). 1. From a practical perspective, it is an extension of technical content and therefore arguably of skill. 2. From an administrative perspective, it provides additional teaching content, that is, more seminars, more gradings, more of everything. 3. From the perspective of personal tradition, it reintroduces, cumulates, or expands the teachings of the original sensei of the lineage, which might have been fragmentary. 4. From a marketing perspective, it might simply be summarized under “customer retention.” 5. From a sport perspective, it allows for more gold medals and titles, which together with grades, are one of the spices of the Okinawan dōjō industry.

When looking at the teaching contents of Okinawan karate kobudō schools since the 1950s, it is easy to observe that teaching content expands further and further in almost every dōjō and association. At some point in the future, maybe in 50 or 100 years, the teaching content will be so vast there is little chance to learn it all in a lifetime. All of this is valuable and might be requested by various sensei and the students as well, who are dōjō owners themselves and need more and more stuff to teach and test students for. It might also simply be the love, joy and pride for kobudō.

To wrap it up: A bō-kata that was obviously never taught in Okinawa or fell in disuse half a century ago is being taught again in a specific school. Call it refurbished, recreated, reenacted, reinvented, or rediscovered etc. That kata is Kongō no Kon.

Now, Kongō no Kon appears on some old kata lists, and from that might arose the wish to reintroduce them both on Okinawa as well as in the branches abroad. It was always a stain for Okinawa that the students of Taira obviously did not learn his whole set of techniques or weren’t able to maintain it, particularly since Kongō no Kon exists in mainland in the Sakagami lineage and the Inoue lineage and probably elsewhere since the late 60s or early 70s. For reasons of simplicity, I will take up the Inoue lineage here for my analysis. Remember I have been asked about the matter so don’t blame me. Well then, lets gets started with Kongō no Kon.

Inoue already published Kongō no Kon in 1974 with photos and descriptive text for each move in great detail, and including the kata’s “application kumite,” or what some people would call “bunkai” or “oyo.” This publication is pretty rare and in Japanese, so most people will have neither opportunity nor skill to study it by themselves, but there are one or two videos of it online. Yet, it is all in mainland Inoue style, so Okinawans would need to “recalculate” the techniques to their own ways. This is because the Okinawan Taira lineage developed along all sorts of different and partly idiosyncratic methods since the 1970s. That is, existing content of Kongō no Kon in either film, text and photographs, or in the memories of the elders would need a lot of work to make it look like authentic Okinawan Taira lineage.

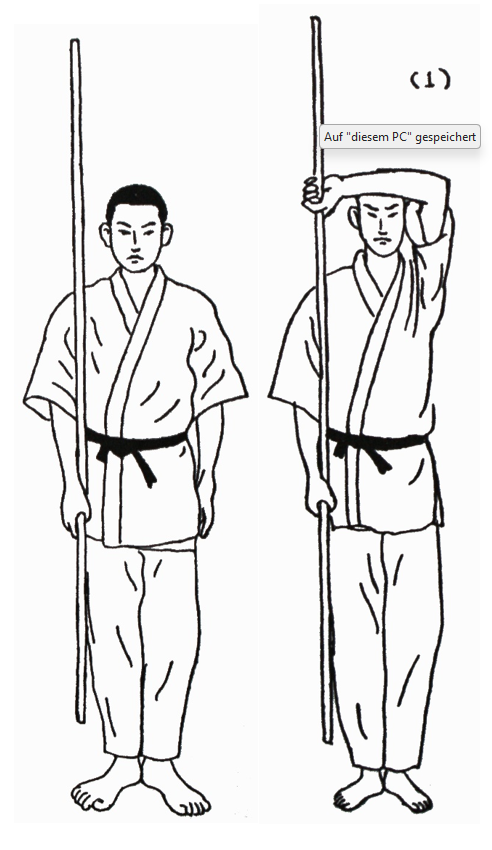

For instance, in Inoue lineage, the kata start with a step backward, but in Okinawa it begins with a step forward most of the time. The front strike of Inoue is performed in the order of jōdan-kamae, jōdan-uchi, and uke, while in Okinawan Taira lineage, there is first a jōdan-ura-uchi with the rear end of the bō, followed by the front strike that ends at the hip level, followed by a chūdan-zuki and then either a chūdan-kame or a chūdan-uke. Accordingly, the morphological order of techniques as well as their outward appearance are obviously quite different.

Taira didn’t perform thrusts (tsuki) often after front strikes and neither does Inoue, but in Okinawa, it is done all the time. It has actually been made a landmark, fixed in what is known as “Bō Kihon Nr. 3.” Inoue’s furiage-uchi is also quite different and would need to be adapted as well. And, as a general rule, while Inoue doesn’t perform a thrust (tsuki) after the front strike, he does a long sliding thrust (nuki-zuki) at almost every kata’s end. Okinawan Taira lineage on the other hand mostly does normal thrust at the end, except in the very high kata.

So, these are several issues of the “style sheet,” habits of ways of doing things that are specific and unique to certain factions. As a result, while all the kata themselves basically remain the same, they make a completely different outward impression, and have a very different practical reasoning as well. Therefore, to make rediscovered techniques look like authentic Okinawan Taira lineage, they need to be adapted to various specifics and characteristics. Or in other words, to revive Kongō no Kon as an authentic kata of Okinawan Taira lineage, one would first need to research and understand all the details of what Inoue does in all of his kata versions. Only then one is able to compare each kata of their own school to those of Inoue, and by this become able to “recalculate” it to Okinawan Taira lineage style, or one’s own dōjō style. That is, you decipher a “code x” to your own “code y”, or a “style sheet 1” to your own “style sheet 2.” It is literally a code since the terms used for the techniques are different as well: Furiage in one school might mean something different in another. And it is literally a style sheet because it defines the outward appearance, as described in a previous article. This all needs to be studied and understood first.

Next, it is important to know that Taira created Kongō no Kon by himself, just like he created or modified almost everything else. When considering Taira’s full corpus of bō kata, Kongō no Kon has little to nothing new to offer. It is basically a collection of combinations and enbusen from several other existing kata. However, since Okinawan Taira lineage forgot some kata long ago, most people cannot know the kata, techniques, and combinations from which Taira created Kongō no Kon.

This being said, and since I was asked to express my opinion, let me tell you that Kongō no Kon is based on elements taken from Sueyoshi no Kon, Sesoko no Kon, and Soeishi no Kon, that is, some of the highest and longest bō-kata of the Taira lineage. It should be noted that, as a general trend, these three kata were partly or completely lost long ago on Okinawa. However, as the revival of Kongō no Kon shows, they might probably be reinvented or reintroduced as well at some point, but naturally these are confidential activities so they will probably simply be presented one day as if they were handed down in personal tradition ever since.

Also note that since this is not a PhD thesis but only my personal assessment after being asked my opinion twice, I am not going into every detail as to what combinations of Sueyoshi no Kon, Sesoko no Kon, and Soeishi no Kon were used by Taira to create Kongō no Kon.

Instead, I will just provide a video of Kongō no Kon here, plus a translation of Inoue’s 1974 description of it below. As an important point, I have used and translated the original terminology so you can immediately see the difference in practical perception when compared to the terminologies used in Okinawa Taira lineage. Note that I am not a member of any association, so it might look a little different than it is done in the Inoue school.

Remember these are just quick examples I worked out this morning just for the fun of it.

Kongō no Kon (Inoue 1974)

Preparation

Body at the position of attention (ki o tuske).

Bow (rei).

Get set (yōi).

Go (hajime).

Lane 1

1. Place your left foot backward, with a right outside deflection (soto-uke).

2. Right inside deflection (uchi-uke).

3. Place your left foot forward, with a left reverse horizontal strike (gyakute yoko-uchi).

4. Place your right foot forward, with a right horizontal strike (yoko-uchi).

5. Scooping deflection (sukui-uke).

6. Lower-level reverse strike (gedan ura-uchi).

7. Reverse upward swing strike (gyaku furi-age-uchi).

8. Sweeping deflection (harai-uke).

9. Upper-level strike (jō-uchi).

10. Outside deflection (soto-uke).

Side lane 1a

11. Move your right foot slightly to the right, and rotate 90° counterclockwise, towards absolute direction left, and assume the posture of the pull-down strike (hikiotoshi-uchi).

12. Place your right foot forward, with a combing-up strike (kakiage-uchi).

13. Upper-level strike (jō-uchi).

14. Place your left foot slightly to the left, with a scooping deflection (sukui-uke).

15. Raise your right foot, with a lower-level reverse strike (gedan ura-uchi).

16. Put your right foot down and forward, with a sweeping deflection (harai-uke).

17. Upper-level strike (jō-uchi).

18. Upward swing strike (furi-age-uchi).

19. Upper-level strike (jō-uchi).

20. Outside deflection (soto-uke).

Side lane 1b

21. Move your right foot slightly to the left, rotate 180° counterclockwise to your rear, towards absolute direction right, and assume the posture of the pull-down strike (hikiotoshi-uchi).

22. Place your right foot forward, with a combing-up strike (kakiage-uchi).

23. Upper-level strike (jō-uchi).

24. Place your left foot slightly to the left, with a scooping deflection (sukui-uke).

25. Raise your right foot, with a lower-level reverse strike (gedan ura-uchi).

26. Put your right foot down and forward, with a sweeping deflection (harai-uke).

27. Upper-level strike (jō-uchi).

28. Upward swing strike (furi-age-uchi).

29. Upper-level strike (jō-uchi).

30. Outside deflection (soto-uke).

Lane 1 – End combination

31. Rotate 90° counterclockwise toward your left and prepare for a lower-level deflection (gedan-uke) towards absolute direction front.

32. Lower-level deflection (gedan-uke).

33. Lower-level thrust (gedan-zuki).

Lane 2

34. Move your left foot slightly to the right, rotate 180° clockwise toward your rear, with a hooking block (hikkake) toward absolute direction rear.

35. Pull your right foot back a little, with a scooping deflection (sukui-uke).

36. Lower-level reverse strike (gedan ura-uchi).

37. Sweeping deflection (harai-uke).

38. Upper-level strike (jō-uchi).

39. Outside deflection (soto-uke).

40. Switch your right hand to the reverse grip (gyakute), place your left foot forward, and perform a knock-away strike (hataki-uchi).

41. Both-handed reverse-grip thrust (ryō gyakute-zuki).

42. Place your right foot forward, and perform a knock-away strike (hataki-uchi).

43. Both-handed reverse-grip thrust (ryō gyakute-zuki).

44. Switch your right hand to regular grip (honte), move your left foot slightly to the left, and perform a scooping deflection (sukui-uke).

45. Lower-level reverse strike (gedan ura-uchi).

46. Reverse upward swing strike (gyaku furi-age-uchi).

47. Sweeping deflection (harai-uke).

48. Upper-level strike (jō-uchi).

49. Outside deflection (soto-uke).

Lane 3 – Bridge right / left

50. With the right foot as the pivot, rotate 180° counterclockwise to your rear, place your left foot backward towards absolute direction rear, and turn towards absolute direction front, with a sweeping deflection (harai-uke).

51. Upper-level strike (jō-uchi).

52. Outside deflection (soto-uke).

53. Place your right foot to the side of your left foot, switch your right hand to reverse grip (gyakute), and assume the upper-level horizontal posture (jōdan yoko ichimonji kamae).

54. Lower-level horizontal posture (gedan yoko ichimonji kamae).

55. Turn 90° to the left, towards absolute direction left, with a both-handed reverse-grip scooping deflection (ryō gyakute sukui-uke).

56. Winding press block (maki-oase).

57. Thrust (tsuki).

58. Turn 180° to your rear, toward absolute direction right, with a both-handed reverse-grip scooping deflection (ryō gyakute sukui-uke).

59. Winding press block (maki-oase).

60. Thrust (tsuki).

Lane 3 – straight forward

61. With the left foot as the pivot, rotate 90° clockwise, place your right foot backward towards absolute direction rear, and perform a both-handed reverse-grip reverse hooking block (ryō gyakute gyaku hikkake).

62. Prepare for a winding press block (maki-oase).

63. Winding press block (maki-oase).

64. Place your right foot forward, with a both-handed reverse-grip rising strike (ryō gyakute age-uchi).

65. Switch your right hand to regular grip (honte), and perform a lower level reverse strike (gedan ura-uchi).

66. Lower-level sweep (gedan-barai).

67. Upper-level strike (jō-uchi).

68. Sliding thrust (nuki-zuki).

69. Outside deflection (soto-uke).

End

Restore the bō to its initial position (osame-bō)

Return to a posture of attention (ki o tsuke),

bow (rei).

Finally, here’s a fun question for all those Okinawa dialect otakus out there: How do you pronounce Kongō no Kon in Okinawan dialect?