In the list of items housed in the Okinawa Prefectural Museum, there is item #1030, a short sword. The description adds,

“Legend has it that Ufumura Ōji [=Prince Chatan] killed Priest Kurogane with this blade.” (Note 1)

What kind of story is this?

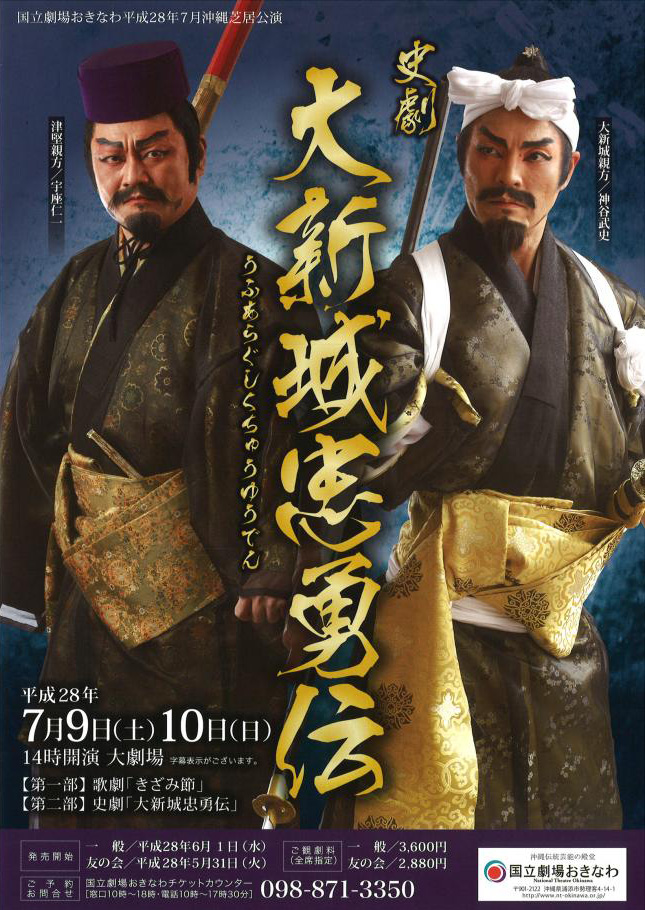

It is said that once upon a time, during the reign of King Shō Kei (r. 1713–1751), there was an evil priest who used sorcery to seduce his female followers. The evil priest is Kurogane Zasu, literally “The Iron Priest.”

When this rumor reached the ears of King Shō Kei, he ordered his younger brother, Prince Chatan, to end this. Prince Chatan investigated the case, and it turned out that the rumor was true. So, Prince Chatan invited Kurogane Zasu, and said, “Let’s play a game of Go.” The prince was planning to take advantage of a break in the Go game and kill the Iron Priest, but the priest saw through his murderous intent.

So the Iron Priest suggested, “Let’s not make it just a game of Go, but a competition. If you lose, I will receive your topknot, which is the life of a samurai. If I lose, I will present you my ear, which is my pride, ok?”

The prince accepted the priest’s proposal, and the match became even more heated. As the situation gradually turned favorable for Prince Chatan, the priest tried to escape, but Prince Chatan pulled out his sword and slashed the priest’s face and cut off his ear. Hating to be defeated, the Iron Priest died cursing Prince Chatan.

After that, the priest’s ghost began to appear in Prince Chatan’s home, and every time a son was born to him, they continued to die young. Therefore, when a baby boy was born in the prince’s household, they chanted, “A great girl has been born,” to avoid being haunted by the Iron Priest.

This anecdote eventually became a folk song and was said to be sung throughout the Ryūkyūs, and even today there is a YouTube video as a comic story.

Background of the story

The Iron Priest, who is generally described as an evil monk, is said to be modeled after the real-life priest Jōkai, the 18th head priest of the Gokoku-ji Temple of the Shingon sect in Naha City. According to the History of Okinawan Buddhism (Okinawa bukkyō-shi), “Priest Jōkai was killed by Prince Chatan because he blamed him for his mismanagement.”

Furthermore, in the Old Records of the Ryūkyū Kingdom (Ryūkyū-koku kyūki), it is written that “The abbot Jōkai requested with a document that a governor monk be established.”

From this it is thought that the priest was aiming to expand the power of Buddhism.

On the other hand, Prince Chatan who appears in the story is said to be Shō Tetsu (1703–1739), the second son of the 12th king of the Ryūkyū Shō clan, King Sho Eki (1678–1712). Shō Tetsu was later adopted by Chatan Ōji Chō’ai to become the 2nd generation of the Ufumura Udun, and became known as Chatan Ōji Chōki.

By the way, it is said that Prince Chatan used the Jiganemaru to cut the priest. It should be noted that item #1030 of the Okinawa Prefectural Museum says the sword is a tantō, while the Jiganemaru is a wakizashi. So I wonder if the Chatan-nakiri would be more fitting instead? In any case, it is a legend, so the reference to royal swords was probably meant to say “royal might destroys evil religion – order restored.”

Note 1: Sonohara Ken (Okinawa Prefectural Museum): About the Museum of Local History (Heimat Museum) affiliated to the Okinawa Prefectural Education Association (Okinawa-ken kyōiku-kai fusetsu kyōdo hakubutsukan ni tsuite). Okinawa Prefectural Museum Bulletin No. 28, 2002, p. 46.