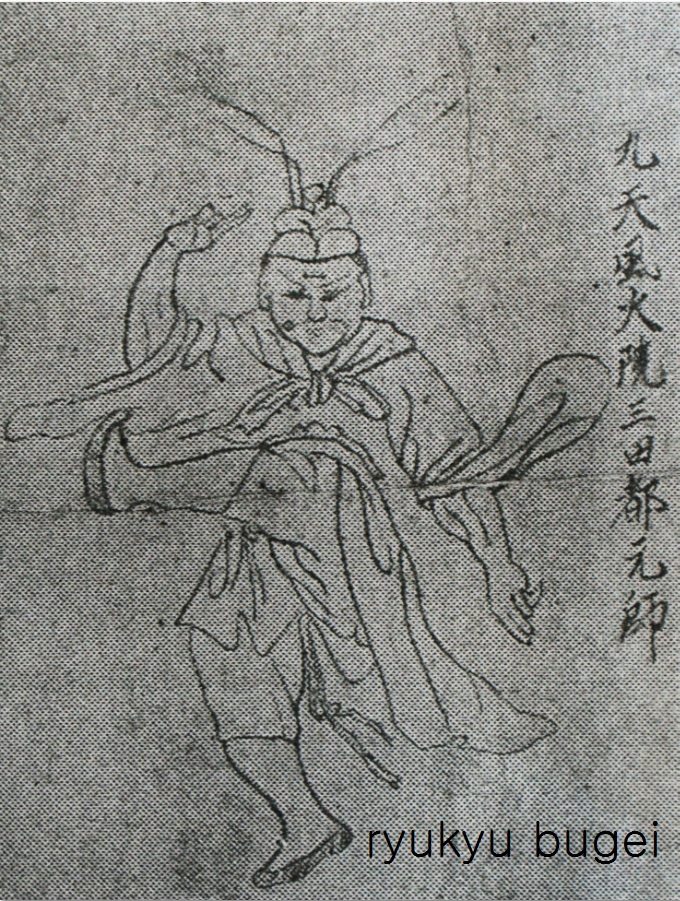

In the prewar-years Miyagi Chōjun, the founder of Gōjū-ryū Karate-dō, possessed two hanging scrolls depicting what is considered a god of war named Būsāganashī. One of these scrolls Miyagi presented to a student of his, Madanbashi Keiyō. While during the 2nd World War Miyagi’s scroll had been destroyed, in the early postwar era Madanbashi had a wooden statue carved on the model of his scroll by a native of Saipan, one of the Mariana Islands. Afterward, Madanbashi presented the statue as a gift to Miyagi Chōjun, who revered it as the Bujin (Būsāganashī) – the god of military arts – of Gōjū-ryū Karate-dō (Kai 2004).

Iha Kōshin noted, that after Miyagi Chōjun’s death in 1953, the building of the Jundōkan Dōjō in Naha Azato – which was finished on April 30th, 1957, with training commencing May 1st – was only possible with the patronage of the bereaved Miyagi family, who at this occasion presented this Būsāganashī statue as a commemorative gift to Miyazato Ei’ichi. Placed inside the Jundōkan in Naha Azato at the time, it can still be found there today. A picture of the statue, accompanied by a short description, also appeared in Miyazato Ei’ichi`s 1978 book on Gōjū-ryū (Miyazato 1978).

Now, what is the story behind this Būsāganashī?

Tokuda Anshū, a nephew of famous Karate expert Tokuda Anbun, provided the oldest written source known to me on the existence of the Būsāganashī, having been published in 1956, noting:

Until today, I cannot forget the fantastical moment when I devoutly gazed at the picture of the Būsāganashī. Dressed with a headpiece and long robe, the picture depicted this deity of Karate in a curious pose. Seeing this drawing, I was touched at the bottom of my heart and fatally needed to smile. This deity is being revered in the shintōistic family altar of the Gōjū-ryū Senbukan Karate-dōjō in Nakajima-chō in the city of Kawasaki. It is shown in the posture of a kick. This picture is a replica taken from the book Bubishi, which had been kept and guarded like a treasure by Miyagi Chōjun, the former teacher of the Dōjō director Izumigawa Kanki (泉川寛喜, founder of the Senbukan 泉武館 in 1939). Until before the war, this Bubishi had been stored in the Temple of Confucius in the district Kume in Naha, Okinawa, of which master Miyagi produced himself a copy. Moreover, the picture in the Senbukan-Dōjō is a copy of this copy.

Tokuda 1956: 43-48

Several essential pieces of information are contained in this part of the article, helping us further tracing the origins of the Būsāganashī. First of all, according to Tokuda the picture of the Būsāganashī had been copied from the document Bubishi, which refers to a book on history, technique, and philosophy of martial arts having been transmitted to Okinawa from China (Fist printed as a supplement in Mabuni 1934, and later described in more detail by Tokashiki 1995; Ōtsuka 1986 and 1998, and McCarthy 1995). According to Tokuda, this Bubishi had been stored in the Temple of Confucius (Kume Kōshibyō 久米孔子廟, generally known as the Kume Shiseibyō 久米至聖廟), which refers to the Kume Shiseibyō shrine complex in Kume. See some photos further below.

According to the Kume Sōseikai (Shiseibyō Visitor Information, no date), the Kume Shiseibyō was built in 1676 in Kume Village to honor Confucius and the Four Correlates, Yanzi, Zengzi, Zisizi, and Mencius (顔子・曾子・子思子・孟子). In 1671, the headman of Kume, Kin Seishun Gusukuma Uēkata (金正春城間親), received authorization from King Shō Tei (尚貞王) to build a temple for Confucius. In 1672 the area at the foot of the Izumisaki Bridge was selected, and work began, with completion of the main building in 1674. During the Second World War, however, buildings such as the Taiseiden and the Meirindō, as well as icons, the library, and so on were destroyed.

According to Hokama Tetsuhiro, on the other hand, it was the Tensonbyō in Naha Wakasa that served as the actual depository for the Bubishi (Hokama 2003: 35). This Tensonbyō was also destroyed during the war.

Accordingly, we must assume that the Bubishi –stored in either the Temple of Confucius or the Tensonbyō – was destroyed, too.

When after the war plans for rebuilding the Temple of Confucius began, the former military road No. 1 – now National Route 58 – passed through the former temple precinct and left no room to rebuild the temple on its old site. For this reason, the Kume Sōseikai chose the precinct of the Tensonbyō temple in Naha Wakasa as the site for rebuilding the temple.

Next, let us turn towards the old, post-war Tensonbyō in more detail. According to the Kume Sōseikai, the Tensonbyō was dedicated to the supreme deity of popular Chinese Taoism, which had been introduced to Okinawa by the so-called 36 clans of Kume, i.e. people from southern Chinese Fujian province (閩人=福建人) who immigrated to Okinawa since the 14th century, and who stayed in contact with China for centuries afterwards.

Inside the current precinct, we find a visitors information board, stating in English:

Tensonbyō is used to worship those who defended the country and helped people. As we know there are the gods of Taoism, including Kan Wu who would die for justice and used to be called ‘Kan Te Ou’ and the god ‘Ryu Ou’ who could control the water.

Kume Sōseikai Info Board

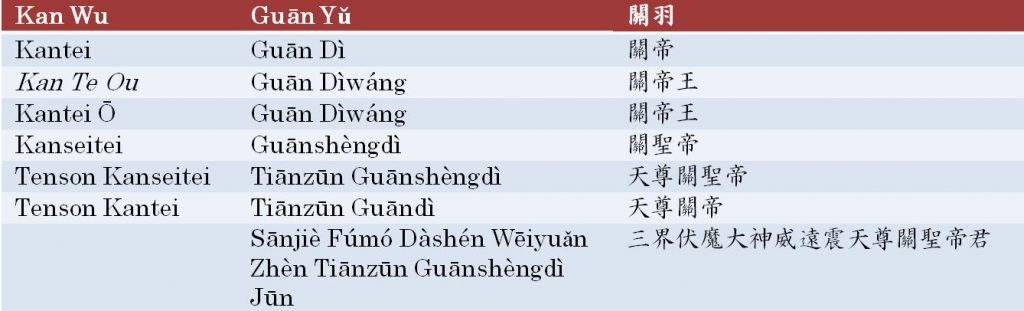

“Kan Wu” is the Japanese reading of the Chinese name Guān Yu (關羽, ?–219), famous general of the Shu, perceived as a fearless warrior, known for his virtue and loyalty and who even appeared in the famous historical novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms. His alias, Kantei Ō (關帝王, chin. Guān Dìwáng), literally means Monarch of the Frontier Post, pointing to his role as a protective patron who secured the country’s borders (see Table 1 for alternative names used for Guān Yu).

“Ryu Ou” (龍王, chin. Lóng Wáng), literally Dragon King, is the god who governs the waters. It actually refers to the four dragon kings of Chinese mythology, which – as heavenly rulers – govern the four oceans, i.e. the oceans of all cardinal points, and also can manipulate clouds and rain and would raise havoc if provoked. In the Journey to the West, one of China’s four classical novels, a Dragon King is one of the main characters in the tenth chapter.

Kume Shiseibyo entry gate (photo by aq)

Plaque inside the Shiseibyo shrine complex, giving the Tensbyo and to it Kantei Ō (關帝王, chin. Guān Dìwáng) and “Ryu Ou” (龍王, chin. Lóng Wáng). (photo by aq)

The Tensonbyo (photo by aq)

Ryu Ou 龍王, chin. Lóng Wáng, literally Dragon King, is the god who governs the waters. It actually refers to the four dragon kings of Chinese mythology. (photo by aq)

Tensonbyo altar (photo by aq)

Kantei Ō 關帝王 (Chin.: Guān Dìwáng), literally “Monarch of the Frontier Post.” This is actually Guān Yu. (photo by aq)

In what period of Chinese and Ryūkyū history the old Tensonbyō had been built? Guān Yu was posthumously deified with his status gradually escalating over the centuries. In 1614, the Wanli Emperor bestowed on Guān Yu the title of “Saintly Emperor Guan, the Great God Who Subdues Demons of the Three Worlds and Whose Awe Spreads Far and Moves Heaven” (Sānjiè Fúmó Dàshén Wēiyuan Zhèn Tiānzūn Guānshèngdì Jūn 三界伏魔大神威遠震天尊關聖帝君). This name for Guān Yu for the first time contained the phrasing Tiānzūn Guānshèngdì 天尊關聖帝, with Guānshèngdì being the long form of Guāndì 關帝, equalizing the former thus makes Tiānzūn Guāndì 天尊關帝 (Jap. Tenson Kantei), which perfectly corresponds to the characters on the name plaques still found today written in the Tensonbyō.

After the change from the Ming to the Qing Dynasty, in 1644, the Shunzhi Emperor gave Guān Yu the different title of “Loyal and Righteous Divine Warrior Great Saintly Emperor Guan” (忠義神武關聖大帝). This name in shortened form is “Saint of War” (武聖), which is of equal rank to Confucius, who was known as the “Saint of Culture” (文聖).

From this we can clearly see, that a) in 1614 Guān Yu received a name which in its short form of Tiānzūn Guāndì uses precisely the same characters as are seen in the Tensonbyō shrine, with Tenson 天尊 as the supreme deity of Taoism and Guān Dì 關帝 as another name for Guān Yu, and b) that, because the former was a short form of a title for Guān Yu, he is actually to be considered the supreme Taoist deity the Tensonbyō was dedicated to, and c) that the epoch of its “import” to Ryūkyū most probably was:

- the time between 1614 and 1644, or

- the time after 1644, in order to make a pro-Ming anti-Qing statement, or

- as the name could also have been randomly picked by preference, sometime between the 17th to the early 19th century.

Choosing the name from a political viewpoint as a pro-Ming statement opens different possibilities of involvement with the establishment of the shrine, from possible immigrants or refugees to Ryūkyū, to a statement from the Kumemura community. In any case: Taoistic beliefs were, of course, a significant factor in all the history of Chinese martial arts, and here we see parts of it entering Ryūkyū. Last but not least, an article in the Ryūkyū Shimpō tells, that Kantei Ō (Guān Yu) was worshipped as the guardian deity of the king of Ryūkyū (see: Kantei Ō no Kakejiku ga Satogaeri 関帝王の掛軸が里帰り (A hanging scroll of Guān Dìwáng returning home). Ryukyu Shinpo, 1997/06/26).

Summary and Continuation

The original Bubishi most probably was kept since an unknown date, either in the old Confucian Shiseibyō or the old Taoist Tensonbyō. Both these old temple sites were destroyed during the Battle of Okinawa, and thus the Bubishi was most probably destroyed, too. This is confirmed by the fact that after the war no notice of the existence of the original Bubishi is found anywhere. As with other and even more valuable documents in the history of Okinawa – thinking about the Rekidai Hōan for example – fortune had it that copies of the Bubishi had been made by different individuals before, who must have used the copy kept either in the old Shiseibyō or Tensonbyō, or a copy of this copy.

In order to find further clues, let us continue with Tokuda Anshū:

The deity’s apparel was obviously made after Chinese fashion. In Chinese magic and juggling of old, the Chinese would walk the suburbs and perform their conjuring tricks and juggling. Some people actually take this as an original form of Karate. But I have never heard that headpieces have been mentioned in the history of Karate. For the rest, it would be futile to report about what outsiders told me about Karate only to aggrandize themselves. In light of the present conditions of the Karate boom, I involuntarily recollect the portrait of the Būsāganshī.

Tokuda 1956

We will later see if Tokuda proved himself ignorant and if outfit and origin of the Būsāganashī had something to do with Chinese magic and juggling of old.

Today the name Būsāganashī in most cases is transcribed in Katakana, indicating that it is a loanword from a foreign language. Tokuda transcribes it in Katakana, too, but in the title of his article, he transcribes it as honorable warrior (武者加那志). In his description he notes:

Considering the word Būsā, this is the Okinawan word for warrior, samurai, or soldier (bushi武士), but the respectful phrase ‘venerated samurai’ (o buke-sama お武家様) fits it even better. Considering the word Ganashi (ガナシー「加那志」), this is the respectful suffix of a form of address which conveys sympathy or esteem vis-à-vis a senior person. Such the king of Ryūkyū had been called Ushu-ganashī-mē (ウシユガナシーメー(御主加那志前)) in olden times, i.e. the honorable sovereign.

Tokuda 1956

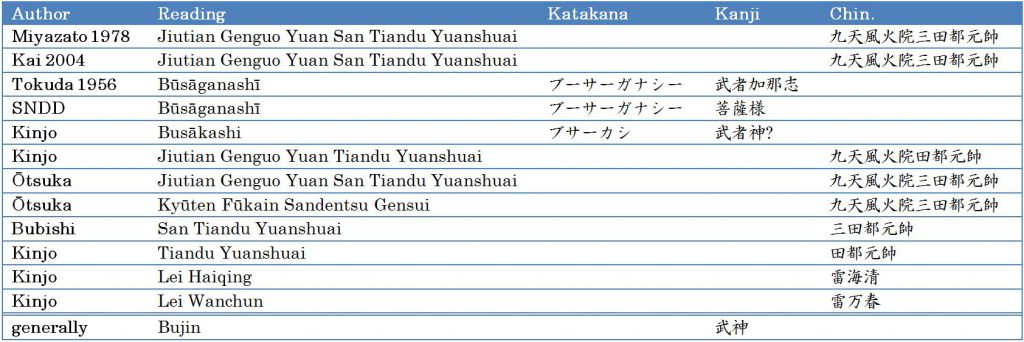

Next, according to the Shuri-Naha Dialect Dictionary, Būsāganashī is the corrupted Okinawan way of reading the Kanji Bosatsu-sama (菩薩様), that is literally “the honorable Bodhisattva,” i.e. a being that is enlightened by the esprit of Bodhicitta. In Chinese the first two ideograms Bosatsu are read Bùsà or Pùsà, and by exchanging the honorofic -sama suffix with the distinctive but otherwise similar Okinawan -ganashi, this wording would conclusively be pronounced Būsāganashī. The following is an overview of the names used by different authors describing the Būsāganashī.

In the above list we notice the phrase “Tiandu Yuanshuai” as part of many of the names given. According to Chen and Fan-Pen (2007) there was a Tiandu Yuanshuai who still today presides over the shadow troupes in Taiwan and that different Chinese shadow troupe traditions all seemed to have their own patron deities.

NOTE: Tiandu Yuanshuai 田都元帥. Also known as Marshal Tian (Tianyuanshuai 田元帥), Marshal Tianfu (Tianfu yuanshuai 田府元帥), Marshal Tiangong (Tiangong yuanshuai 田公元帥), and Lord Tianfu (Tianfu laoye 田府老爺).

Tiandu Yuanshuai had already been revered as a deity by the “Southern Drama” (Nánxì 南戲) opera troupes of the Song and Yuan dynasties, and by numerous regional human actor operatic traditions in Jiangxi, Fujian, and Guangdong ever since (Chen, 2007. p. 81).

Tiandu Yuanshuai is a deified historical figure, who, according to local tradition, was Lei Haiqing (雷海清), a loyal musician in Emperor Xuanzong’s (Minghuang 明皇/Xuanzong玄宗; r. 713-756) court of the Tang dynasty. Van der Loon sees him representing the ultimate military commander leading combats against evil spirits menacing local communities (Loon 1977, p. 166). Zheng believes that Marshal Tian evolved from a local protective deity to one amalgamated with other popular gods (Zheng Qingshui, et al., eds., Fujian Xishilu, 118-40). Schipper shows that, according to a Taoist text, Marshal Tian in fact refers to three deity brothers who once served as jesters and musicians in Emperor Ming’s court (Schipper 1977, p. 83). Ayers and Yuan affirm the popularity of Tiandu Yuanshuai as a patron saint of performing arts and as an exorcising spirit especially in Quanzhou (Ayers 2002. p. 42) and Lee calls him the deity of the Gezaixi (Fujian operatic genre developed in Taiwan) troupes from Fujian (Lee 2008, p. 191). Dean supports the theory of Lei Heiqing as the god of theatre, having been revered in Fujian at least since the Song Dynasty. His cult, within the theatre traditions as well as outside of them, spread all over Fujian. Dean explains that this god was and still is revered today in many local areas as a deity, a protective god, which differs immensely from the role projected upon him in theatre (Dean 1998, S. 195).

And he found his way as a protective deity to Okinawa, too.

Karate and Chinese Kenpō expert and researcher Kinjō Akio researched more detailed insights and pinned down the Būsāganashī’s connection to Chinese martial arts as follows:

Gōjū-ryū`s God of War – The Portrait of the Jiutiān Gēnguo Yuàntián-dū Yuánshuài

The Okinawan Bubishi contains an illustration of a god of war named Jiutiān Gēnguo Yuàntián-dū Yuánshuài. This god of war had been revered by Miyagi Chōjun and is held as evidence that Higashionna Kanryō has had studied White Crane Boxing. Even in today’s Dōjō of Gōjū-ryū Karate, this god of war is worshipped and it is called Busākashi (ブサーカシ) in the Okinawan dialect.

About this matter, I queried master Zhèng Wéncún from the homeland of the White Crane Boxing, the district Yongchūn in Quanzhou, Fujian, and a related tradition actually exists. According to this tradition, already the foundress of White Crane Boxing, Fāng Qīniáng, revered this god of war. And accordingly this god has been revered in all White Crane Boxing gyms of old. For this purpose, a picture was attached to the front wall of the gym and worshipped by all attendees before the martial arts training. However, because of the cultural revolution in Maoist China and other wicked affairs this practice did not survive.

Kinjō 2008: 155-158

Jiutiān Gēnguo Yuàntián-dū Yuánshuài is a Taoist god, which was chosen the immortal master of the White Crane Boxing. According to the legend he is said to have given Fāng Qīniáng the advice to formulate the martial arts according to the spirit of the white crane. Derived from White Crane Boxing, this god reached into the Feeding Crane Boxing (Shíhè-quán 食鶴拳. Japanese: Shitsuru-ken) from Fuzhou.

NOTE: Jiǔtiān Gēnguǒ Yuàntián-dū Yuánshuài 九天風火院三田都元帥. Both Miyazato Eiichi and Kai Kuniyuki called it by this name, but without adding any further description

Tangible References of the Jiutiān Gēnguo Yuàntián-dū Yuánshuài.

In the written tradition of the Bubishi, the name is given as Sāntián-dū Yuánshuài (三田都元帥), correct is, however, Tián-dū Yuánshuài (田都元帥). The picture of this god depicts a figure from the sphere of puppet theater and string puppets play, who is admired as the god of theater, especially in the Quánzhōu region. This figure was well known in Quánzhōu and is even found in the museum of the string puppets performing troupes of Quánzhōu (Fújiàn-shěng Quánzhōu Mùou Jùtuán 福建省泉州木偶劇團). Here I would like to introduce miscellaneous explanations I have been told by the elderly persons of this performing troupe.According to the legend, the following happened in the first half of the Tang Dynasty (1300 years ago [618–907]): A lovely virgin took a walk. In a field she tore off a rice head and ate the raw grains, after which she immediately became pregnant and gave birth to a boy. Her whole family was convinced that the boy was a demonic child, and so they decided that the child had to be abandoned. Then, in the deep of the night, the child was abandoned in a secluded paddy field. Three days later, the mother, unable to bear this situation, started searching for her child. And really, she found it alive and well. According to the legend, it were a big crab and a duck which patronized the child in the flooded paddy field. Now the mother took the child home and raised it secretly.

She devotedly nurtured the child which also received an academic education. He turned out to be a child of prodigy, who ‘heard one thing and thereby learned ten things.’ Such he became a very bright person, pursuing his studies in many different areas, in a little while outflanking his teachers. Later he passed the higher official test at the Imperial Hanlin Academy at first attempt and highest score. He had mastered several arts, which crystallized in his capability in the area of drama and play. Besides he is considered the one who for the first time ever in China invented sheet music. From these reasons he enjoyed the special consideration of the emperor.

“Once a blaze occured in a part of the imperial palace. Many people senselessly zipped around to and fro with big clamor but could not extinct the fire, which on the contrary blazed up more and more. At this time he reached the scene of the fire and ordered all people to withdraw. With all the physical might at his disposal he blew against the blaze, and with this storm the fire was blown away and extinguished on the spot. All people were amazed by his vigor and reverentially demonstrated their respect towards him. For this reason he was also called Léi Wànchūn, the name of a famous Tang era general.”

The emperor, upon hearing this, even felt more sympathetic towards him. And after his death, the emperor bestowed on him the posthumous name Jiutiān Gēnguo Yuàntián-dū Yuánshuài.

Because he had invented the sheet music, he became known to the general public as the ‘god of music’ (音楽の神様) or ‘god of play’ (戯曲の神様). But as he also possessed such huge power, that with one puff he was able to extinguish a severe fire, it is also conceivable that he was regarded as a ‘master of the martial arts.’ I hope to be able to find further evidence supporting this in subsequent research.

At any rate, in the villages in the region of Quanzhou, Jiutiān Gēnguo Yuàntián-dū Yuánshuài is being revered as the tutelary god of villages (村の守護神). And Fāng Qīniáng and all disciples of the White Crane Boxing school traditionally worshipped this god.

In the gyms of old, different gods of war were venerated: In the ‘Boxing Style of the Great Ancestor’ (Tàizu-quán 太祖拳. Japanese: Taisoken) it was Emperor Sòng Tàizǔ (宋太祖, AKA Zhào Kuāngyìn 趙匡胤, founder of the Song Dynasty, 960–1279); in the ‘Boxing Style of Budhha’s Disciples’ (Luóhàn-quán 羅漢拳. Japanese: Rakan-ken) it were the 18 Luóhàn (十八羅漢) as well as the great teacher Bodhidharma (Dámó. Japanese: Daruma Daishi 達磨大師); In the ‘Xìngyì-quán’ (行意拳) it was Yuè Fēi (岳飛), patriot and general of the Song Dynastie (1103-1142), and besides Guān Yǔ (關羽), general of the Shu from the Age of the Three Kingdoms (220–280) has been revered as the founder. This custom could be observed in Taiwan until about 25 years ago. The superstition even goes to such lengths that Sūn Wùkōng (孫悟空, Japanese: Son Gokū), the monkey king from the novel ‘Journey to the West’ (Xīyóujì 西遊記) is being revered as a god of war.

Kinjō 2008 : 155-158

Conclusion

The Būsāganashī is a figure that represents “Tiándū Yuánshuài,” the Chinese god of music and plays.

It is the deification of the historical figure of Léi Haiqīng 雷海清, who served Emperor Xuanzong (rg 713-756) as a musician.

His was also referred to as Xiàng Gong 相公 (Chan 2006, p. 168).

His honorific title was “Marshal Tiandu from the Court of Wind and Fire in the Nine Heavens” (Jiu Tian Feng Huo Yuan Tiandu Yuanshuai)

© 2019, Andreas Quast. All rights reserved.