In my previous article I shared the story of Tsuken Uēkata. At the end of that story, Tsuken Uēkata was interned in Kagoshima after his political intrigue was discovered. So, how, and when did he create Tsuken-bō, and how was it supposedly handed down?

According to legend, after being released from Satsuma, Tsuken Uēkata traveled to Tsuken Island and lived out the rest of his life in a secluded cave situated in the northeastern part of the island. The cave came to be referred to as Pēkū-gama or Pēkū Cave.

As I said before, on Tsuken Island itself, Tsuken Uēkata Seisoku was referred to as either Chikin Uēkata or Chikin Pēkū. Of course, Chikin is the dialect pronunciation of Tsuken, and Uēkata is a high rank within the royal government. As regards Chikin Pēkū, it might be a short form of Pēkumi, which is the way of pronouncing the title Pēchin only when the bearer is a fief holder. That is, both designations refer to him as either the general estate-steward (Uēkata) or the assistant estate-steward (Pēkumi) of Tsuken Island.

Assuming this is the case, Pēkū-gama means nothing but “the cave of Tsuken Pēkumi,“ or otherwise, “the cave of Tsuken Uēkata.”

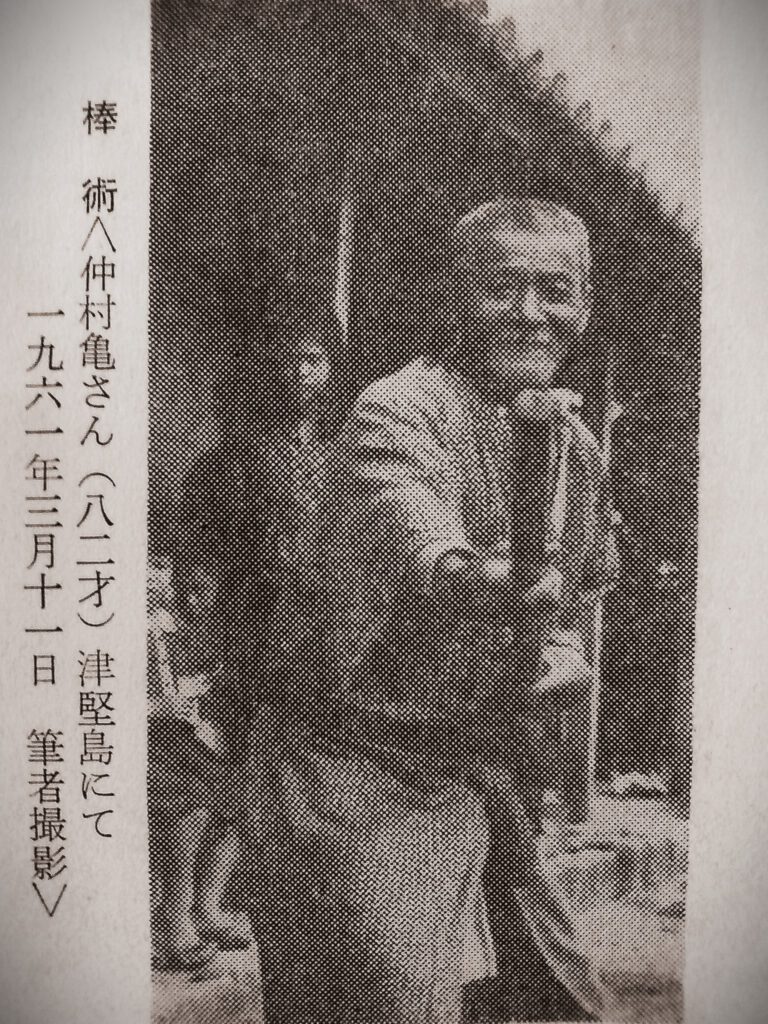

Within the folk tradition of Tsuken Island, Tsuken-bō was handed down when Tsuken Uēkata Seisoku taught bōjutsu to a person called Tsuken Akan’chū at Pēkū Cave.

Tsuken Island has a long history of carrot cultivation, so much so that it is also known as “Carrot Island.” Even the ferry toward Tsuken Island has a pair of carrots drawn on it. Now, carrots can tan your skin if you eat a lot of them. This is because if the body has enough vitamin A, it no longer converts the beta-carotene, but instead stores it in the outermost layer of the skin, which gives it an orange-ish to brownish tone. Since Tsuken Akan’chū literally means “Red Man from Tsuken,” I thought, “Hmm, maybe he was a carrot lover with carotenosis, and therefore the nickname?”

What a funny idea, isn’t it?

In any case, having studies the details of the matter in detail, Katsuren Moritoyo concludes that there was a 200-year difference in time between Tsuken Uēkata and Tsuken Akan’chū, and that a direct teacher-pupil relationship was impossible (see, Okinawa Bō-odori, 2019).

How did Katsuren establish the life dates of Tsuken Akan’chū? Since I have never heard it before, I believe the following to be new information. Let me explain. On Tsuken Island there was an extended patrilineal kinship group (monchū) called Akan’chū. This means that Akan’chū was kind of a clan name, albeit an unusual one. The former houses of the Akan’chū clan were situated somewhat far from the head house (mutuya) located in the center of the village. Since the head house is the one first established, and houses of each new family were always positioned slightly further away from the head house, representing distance in time of origin in relation to the head house, Akan’chū is considered to be a relatively young clan (read about the development of villages and monchū here). In fact, some people say that the Akan’chū is a branch of the Asato clan.

In any case, from all that has been researched so far, Tsuken Akan’chū lived at least 200 years after Tsuken Uēkata, and therefore, a personal tradition and instruction of techniques is impossible.

In short, while martial arts techniques of Tsuken Uēkata might have existed in the 17th century, it is unclear how they supposedly have reached the person Tsuken Akan’chū around 200 or so years later. Even if the stories about Tsuken Uēkata and Pēkū Cave are true, wouldn’t it be more realistic to consider one or several of the ubiquitous bō-odori to become Tsuken-bō, Tsuken no Kon, Tsuken Sunakake, Tsuken Akan’chū or the like within the general trend of bujutsu-fication in early 20th century Okinawa?

Here again I would like to remind the reader that in the original description of Tsuken-bō by Majikina Ankō in 1923 it is said that “Tsuken-bō is a method handed down by Tsuken Uēkata Seisoku, and it closely resembles Jigen-ryū swordsmanship.” While it can be that Tsuken Uēkata learned Jigen-ryū, especially when considering the impossibility of a direct personal instruction of Tsuken Akan’chū, where in todays Tsuken kata family – Tsuken-bō, Tsuken no Kon, Tsuken Sunakake, Tsuken Akan’chū – can be found any hint to Jigen-ryū?

The Jigen-ryū, which originated in Satsuma, is characterized by fierce slashing attacks with the long sword, by emphasizing the first attack in an encounter, and from there by continuous follow-up techniques. It has a practice method of slashing violently left and right against a standing vertical wooden log (tateki-uchi) and the “dragonfly posture” is also mentioned regularly when it comes to historical claims regarding Tsuken-bō.

Make up your own mind and watch the “dragonfly posture” and log striking of Jigen-ryū below. What do you think?

Btw, among the many traditions of the Tsuken-bō, there is also Shubukan no Gusan, a kata with a short stick called Gusan in Okinawa. While the name and weapon sounds unique, the kata is exactly Tsuken-bō of Inoue-Taira lineage, with occasional sliding thrusts (nuki-zuki) as add-ons probably taken from Shirotaru no Kon. I am telling you this only because it is impossible for most people to figure out, even on Okinawa.

© 2023, Andreas Quast. All rights reserved.