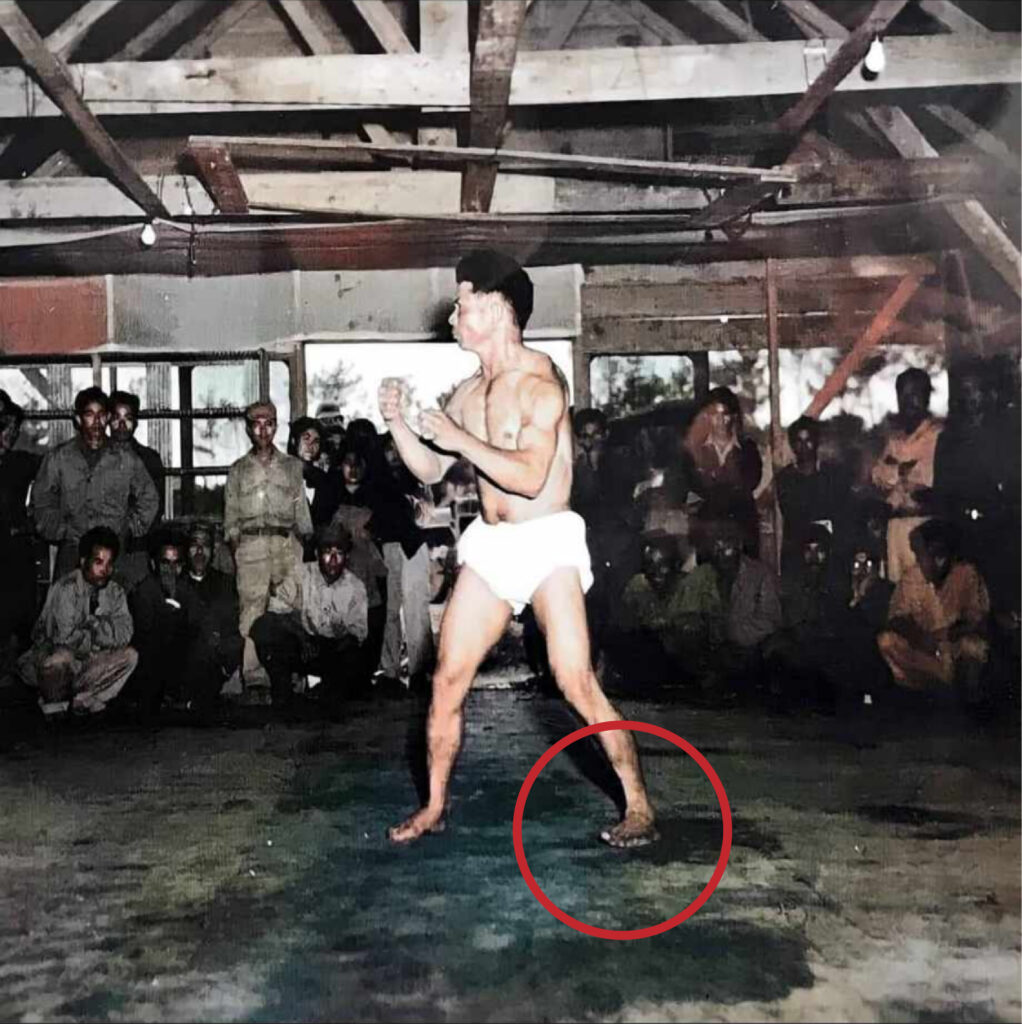

I talked to a friend in the US yesterday about the old dōjō in Okinawa. She told me about this photo where there was obviously a dirt floor, as can be seen in the color photo below that she had. It really looks like as if the feet and lower legs are covered in dirt (see red circle).

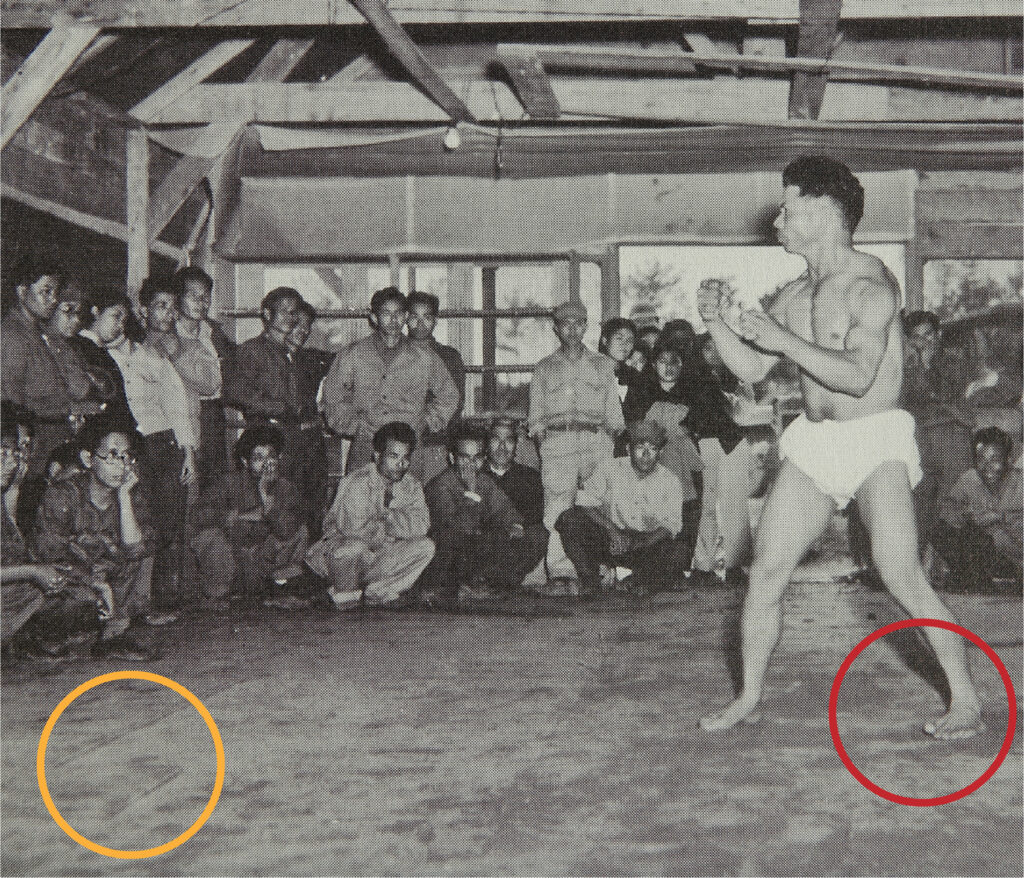

On a closer look and in direct comparison to an unaltered photo I located elsewhere, the dirt must be an effect of photo post-processing by means of automated artificial intelligence. In other words, it is a misinterpretation of shadows by the software.

Even though it is difficult to see, from the unaltered photo, it sems there are rectangular shapes and lines (see orange circle) that point to tiles or stone slabs, so the surface where Uechi stands on might be concrete or screed, maybe a not-yet finished area of a tile floor?

Anyway, there is a description to the photo in the Okinawa Karate Kobudō Encyclopedia (2008) which I used and expanded on in the following.

The foundation of Uechi-ryū was laid by the first generation, Uechi Kanbun (1877–1948), and the second generation, Uechi Kanei (1911–1991), developed the curriculum and spread the style, sent many talented people to the world, and laid the foundation for Uechi-ryū as a solid contemporary Japanese budō.

Uechi Kanbun was born in 1877 in what is now Motobu Town, Okinawa Prefecture. He appears first in a historical record of twenty years later, when prefectural governor Narahara Shigeru reported a list of conscription evaders to Minister of War Katsura Tarō. According to the report, Uechi Kanbun stowed away for China on May 9, 1898.

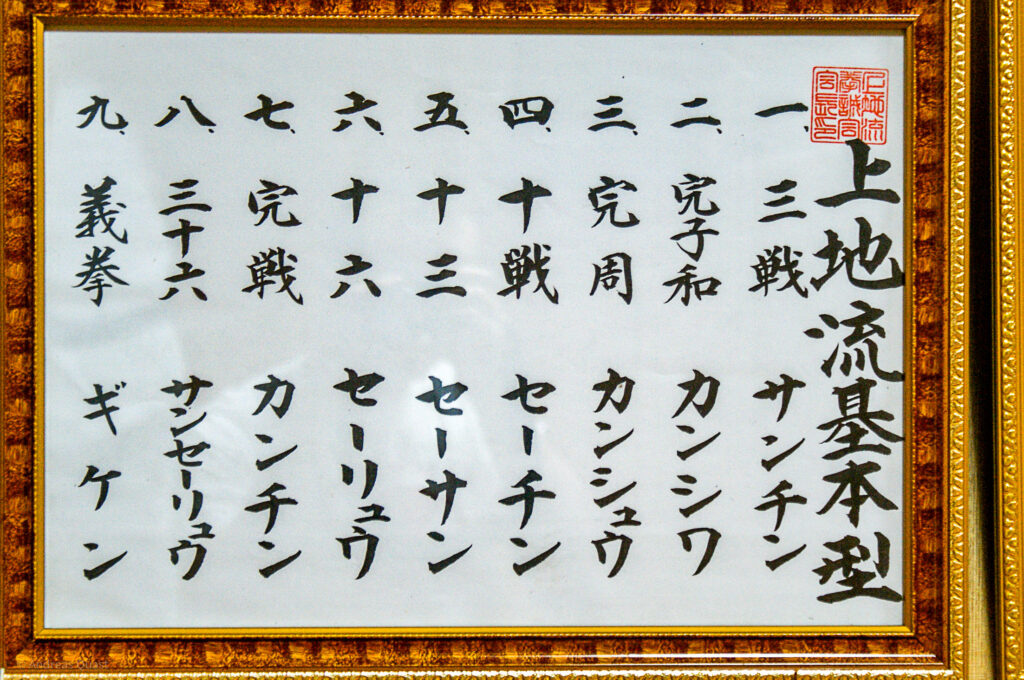

While living in Fujian Province for several years, Uechi Kanbun learned Chinese kenpō. He returend to Izumi Village in the northern part of Okinawa around 1910 and is said to have brought with him the three kata of Sanchin (Three Battles), Sēsan (13), and Sansēryū (36).

The postwar depression after World War I resulted in Okinawan labor migration, mostly to mainland Japan.

“The shock waves first struck farm families, then pounded related businesses and banks, which failed one after another. Employers could not pay their employees, and, unable to collect taxes, even the Okinawa Prefectural Government went bankrupt.” (Rabson 2012)

After the collapse of sugar prices in 1921, Kanbun Uechi moved to Wakayama in 1924 and worked as a gatekeeper at a textile spinning company in Tebira Town, Wakayama City. Two years later, in 1926, Kanbun Uechi opened a dōjō inside the company housing provided by the spinning mill, and began teaching a small number of disciples, including Tomoyose Ryūyū and Uehara Saburō. In 1927, his son Uechi Kanei also moved to Tebira Town and joined the dōjō.

The 1930s saw a growth of residential enclaves. In 1932, by persuasion of Okinawan young men, Uechi Kanbun opened the Pangainūn-ryū Karatejutsu Research Establishment in a residential enclave of Okinawan residents in Tebira Town, Wakayama City. In Uechi-ryū texts this is sometimes dramatically referred to as a “migrant camp,” but “residential enclave” is more suitable.

1937 marked the begin of the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945), which would become part of a greater conflict, the Pacific theatre of World War II (1941–1945). In the same year of 1937, Kanei Uechi opened a branch dōjō in Nishinari Ward, Ōsaka, which in 1940 was moved to the fast-growing industrial city of Amagasaki in Hyōgo Prefecture. The name Uechi-ryū Karatejutsu was established in the same year. According to testimony, practice contents in this dōjō were centered on kata, kote-kitae, and free sparring (kakeai = jiyū-kumite).

In 1942, when all young men were called to miitary service, Kanei Uechi returned to Okinawa and is said to have opened a dōjō in Miyazato, Nago City, which at some point was closed due to the war. During that time, since 1941, all young men aged twenty-five to forty not in active duty were organized in civil defense units (keibōdan). By mid-1941, virtually all provisions of the general mobilization act were in effect throughout Okinawa. The National Defense Games (kokubō kyōgi), in which the Okinawans used to excel in jūkenjutsu (bayonet fencing), were also terminated in 1942, just as most other activities related to physical education and exercises. Even the Dai Nippon Butokukai’s “Festival of Military Virtues,” continuously held since 1895, was cancelled in 1942 due to the Pacific War.

After the war, in 1946, Kanbun Uechi entrusted the Wakayama dōjō to Tomoyose Ryūyū and returned to Okinawa together with Shinjō Seiryō, Shinjō Seiyū and Tōyama Seikō. Kanbun Uechi then moved to Ie Island, where he passed away in 1948 at the age of 72.

Around the same time, Uechi Kanei began to systematically organize preparation exercises (junbi undō) and supplementary exercises (hojo undō), and devised three kata, namely Sēryū around 1950, Kanshiwa around 1956, and Kanchin around 1960, as well as promised sparring (yakusoku kumite) at some point. Another kata called Sēchin (Ten Battles) was created by Uehara Saburō in the 1950s and Kanshū was created by Seiki Itokazu in 1956. Decades later still new methods are developed and added in individual dōjō, such as Ryūkō (“Dragon and Tiger”) by Takamiyagi Shigeru, or Giken (“Fist of Justice”) by Senaga Yoshitsune.

SONY DSC

Around January 1949, not long after the Battle of Okinawa, Uechi Kanei was invited to the completion ceremony of a temporary gymnasium in Chinen Village established by the Okinawa Civilian Administration (Okinawa minseifu). This Okinawa Civilian Administration was an administration in name only and in reality it was under absolute authority of the United States Military Government of the Ryukyu Islands at the time.

At this new temporary gymnasium, at age 38, Kanei Uechi performs the kata of Sansēryū. Karate demonstrations, dances, and plays were greatly welcomed by the people of those days for cultural recreation. In Uechi-ryū, underwear such as pants or steteko (trousers worn mainly by men made of thin fabric with a hem that reaches below the knee) was rolled up and the upper body was bare during practice. The “pants era” came to an end only after 1958, when karate uniforms were begun to be worn.

BTW, the location of above-mentioned gymnasium is at the current Shurei Country Club Golf Course in Sashiki Town, Nanjō City.

The above is the story of the photo. It should be noted that Uechi-ryū was among the styles who had contracts with US bases for teaching, probably used on-base facilities but also had exchange contracts so that students from base could enter the private dōjō. Also Shimabukuro Zenryō of what is nkown today as Seibukan began teaching karate on a US Army base in 1958. Form there, the main route of propagation was the Uinted States, where dōjō and associations where established one after the other. In short, it was the origin and nucleus of Okinawa karate outside of Okinawa itself. I don’t know the details but this is an interesting point.

After World War II the United States-administered Okinawa issued a higher-valued currency called the B yen from 1946 to 1958, which was then replaced by the U.S. dollar at the rate of $1 = 120 B yen. Upon the reversion of Okinawa to Japan in 1972 the Japanese yen then replaced the dollar. In light of the dollar’s reduction in value from ¥360 to ¥308 just before the reversion, an unannounced “currency confirmation” took place on October 9, 1971, wherein residents disclosed their dollar holdings in cash and bank accounts; dollars held that day amounting to US$60 million were entitled for conversion in 1972 at a higher rate of ¥360.

In short, and this is what I have been told as well, the business with US servicemen, who paid in US dollar, made many dōjō and owners rich. It is therefore no wonder that dōjō one after the other began to sprang up around the main gates of the US bases. This might as well have been the initial motivation for the expansion of the curricula during the 1950s and onwards, as described above.

Like this, karate can be said to have become a new asset for the Okinawans in the postwar era under US government, and a “Bridge between Nations” that brought economic stability to individuals in the region, and set in motion international spread and promotion that continues to provide economic growth to this day.

All of the above, and more: that’s what’s in a photo.

© 2023, Andreas Quast. All rights reserved.