Land registers are formal records kept worldwide by authorities or other government bodies according to specific rules that can differ regionally. They list all land, land rights, the existing ownership and associated rights and encumbrances. It is most often known as land registry (EN), registre foncier (FR), catasto (IT), Grundbucheintrag (DE) and so on.

If the ownership of land is unclear or cannot be proven, several issues may arise. In Japan, this is known as “plots of land of unknown ownership” (shoyū-sha fumei tochi). It refers to land whose owner is unknown even if the land registry (fudōsan tokibo) is checked, or it is land whose whereabouts are unknown even if the owner is known but cannot be contacted. Reasons for it are varied, such as that the owner of the land has not been registered at the time of inheritance.

The issue of plots of land of unknown ownership in Okinawa is radically different from the rest of Japan. In case of Okinawa, if there is no owner registered in the land registry and the owner cannot be identified or contacted, then Okinawa Prefecture or a municipality is registered as the administrator. Land of unknown ownership in Okinawa was mainly caused by the destruction of land-related records during the Battle of Okinawa. The issue is managed by Okinawa Prefecture or related municipalities based on the Act on Special Measures Accompanying the Reversion of Okinawa (Act No. 129 of 1971, hereinafter referred to as the “Special Measures Law on the Reversion of Okinawa.” See Okinawa no fukki ni tomonau tokubetsu sochi ni kansuru hōritsu).

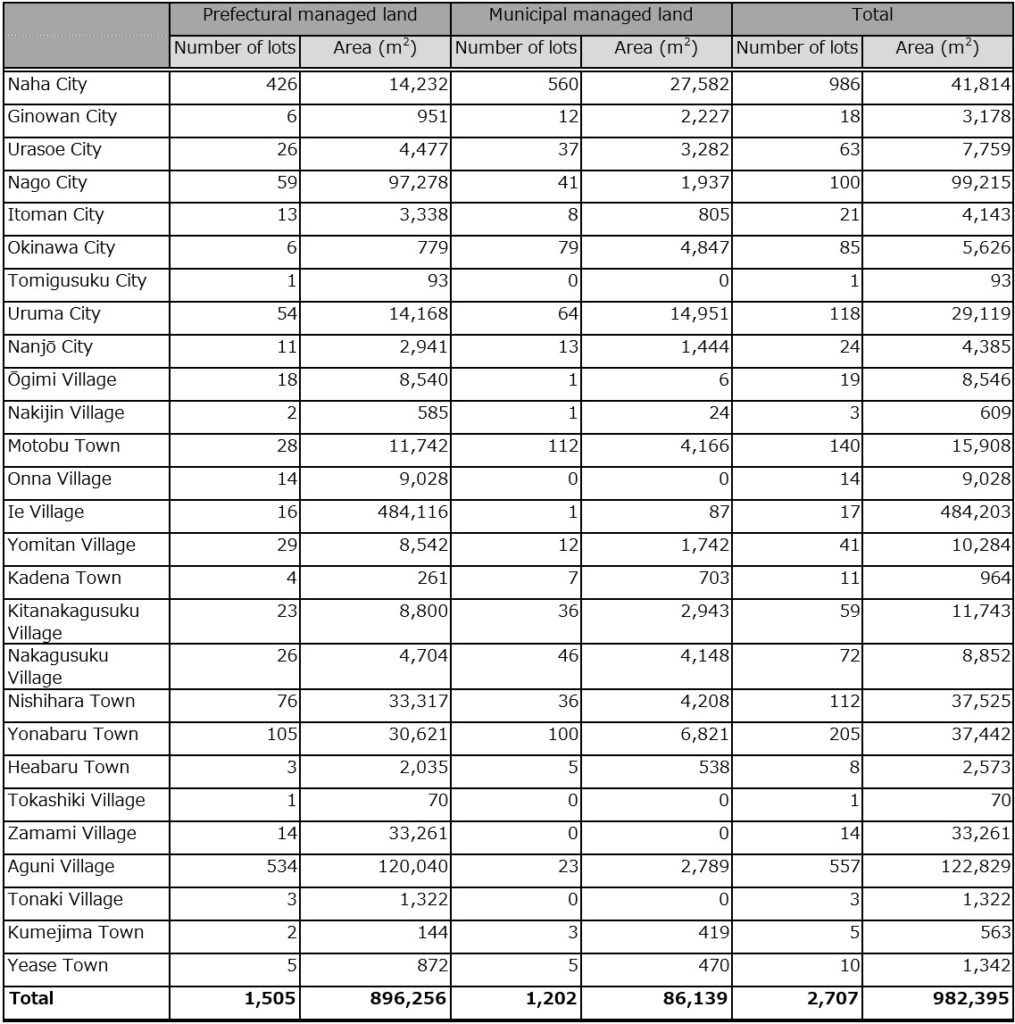

A considerable amount of time has passed since the end of the war, and due to the lack of personal and material evidence, it is often difficult to find the owner and to close a matter. For this reason, the Special Measures Law on the Reversion of Okinawa was amended in 2012 to solve the problems caused by plots of land of unknown ownership. Since the same fiscal year, the Cabinet Office of Japan has been conducting a fact-finding survey of land with unknown owners as a project commissioned by Okinawa Prefecture. As a result of the survey it was found that there are 2,707 plots of land of unknown ownership in 27 municipalities in Okinawa Prefecture, of which 986 plots (about 40%) are in Naha City, combined with 557 plots in Aguni and 205 plots in Yonabaru. 65% of the lots are concentrated in 3 municipalities. Even within the areas of Naha City, Aguni, and Yonabaru, plots of land of unknown ownership tend to concentrate on specific subunits of villages (aza).

From: Cabinet Office of Japan – “Fiscal Year 2018 Investigation Report for Solving Problems Caused by Land of Unknown Ownership in Okinawa Prefecture.”

Of the 2,707 registered plots of land of unknown ownership, 1,125 plots (41.6%) were cemeteries (communal graves and family graves), followed by 692 plots (25.6%) of waste land, 435 plots (16.1%) of residential land, and 212 plots of farmland (7.8%). Of the plots of land of unknown ownership, those that are registered as cemeteries are municipal land, but there are also a certain number of fields and residential land that are also municipal land.

On the other hand, in the representative types of with the largest area, forests and waste lands accounted for 966 parcels (35.7%), followed by cemeteries with 572 parcels (21.1%), and residential land with 359 parcels (13.3%).

A main issue is that records such as public maps and land registries were destroyed during the war, and the US military occupied the site after the war. One example is the dispute over the ownership of land related to the former Tomari Water Purification Plant in today’s Uenoya, Naha City. Although it is registered as city-owned land, an over 90-year-old woman from Naha claimed ownership, questioned the city’s procedures, and demanded the return of the land.

Naha City claimed to have owned the land since before the war, but official records were destroyed in the Battle of Okinawa. Authorization of ownership has been carried out again since 1946 by order of the U.S. military. In principle, three signatures were necessary for authorization, including the guarantor of the neighboring landowner. The water purification plant area, including the land in question, was occupied by the US military, but in 1954, it was returned to Naha City free of charge. The city registered the ownership the following year, but the ownership during that time became obscure. During deliberations at the city council, it was also revealed that the US military had prepared documents suggesting that the land was owned by a third party at the time it was returned to the city.

Moreover, the land in the women’s case had only two signatures, and after and handwriting expertise, there was a suspicion that they were signed by the same person. In 1947, a total of four applications forms were submitted to the Mawashi Village Land Ownership Committee for 4 parcels (2 hectares) of land. A certificate was issued in 1952, and the property ownership was registered between 1955 and 1961.

According to the woman, her parents inherited the land from a member of the House of Peers during the Taishō period (1912–1926) and received the inheritance in 1946. “The city acquired the land illegally in the post-war chaos,” she said, and “I don’t accept that, and the land should be returned.”

The target area was divided into 5 parcels and replaced in 2004, and moved to Naha City’s Tomari Reservoir, Asato Reservoir, and a part of the city water and sewage bureau government building. Disputes over ownership of the property developed into lawsuits, and in 2006 the Supreme Court ruled that the woman lost the case.

The city’s waterworks bureau denies the suspicion that the handwriting is of the same person and claims the legitimacy that “the application was made based on law and the ownership was properly recognized.”

But the issue dragged on. At the Standing Committee on Urban Construction and Environment of the Naha City Council held on 3rd March 2022, the city often struggled to answer commissioner questions about land ownership. The issue is about 18,000 square meters of land in Omoromachi, Naha City, where facilities related to the city’s former water purification plant (closed in 1988) are located. The woman petitioned the city council to recover her property, claiming that her grandfather bought the land in 1925. On the other hand, the city claims that the land has been owned by the city continuously since 1911, and the two sides are at odds with each other.

The woman sued the city in 2003, but the city’s claim was accepted in 2006 and she lost. However, after the trial the woman contacted a handwriting expert in Kanagawa Prefecture for an evaluation. In April 2020, the appraiser concluded that “the signatures of the guarantors for all four lots were made by the same person.” In October 2021, criminal charges were filed against the city for property theft. The woman’s daughter, a woman in her 60s, told the newspapers, “My mother was so frightened that for decades that she was unable to disclose the land issue to the public. I want her to declare ownership of the land while she is still alive.”

In Okinawa after the war, there was a lot of chaos, with organized gangsters (bōryokudan) working behind the scenes on cases of unclear land ownership. According to people involved, the women and some of her acquaintances were assaulted by such gangs over the land in question and they threatened to “kill and bury them if they do anything unnecessary.”

On the other hand, after the war, the city certified ownership according to the administrative procedures of the time, such as public notices and public inspections. A person in charge of the city’s water and sewerage bureau asserted, “The fact that the city owned the land before the war and followed proper procedures to register it after the war has also been recognized in a civil court judgment,” referring to the 2006 judgement. The chairman of the city council, Kudaka Tomohiro, said, “Every citizen who experienced the Battle of Okinawa suffered some kind of damage. We can’t just settle things in court. If there’s anything that the city council can clarify, we will.”

There are still maps in existence that contain a lot of personal information, and this seems to be one of the reasons that certain maps are not, or not anymore available to the public. Releasing such maps to the public could create problems with lawsuits such as in the above woman’s case, because after the war, many private properties might have been taken from their original owners, who might have died in the war, or how lived elsewhere by then.

Under the above circumstances, and the loss of so many lives and records, one can only speculate about the existence or nonexistence of “land grab” in post-war Okinawa. As mentioned above, there are still 2,707 plots of land of unknown ownership in Okinawa, but this doesn’t count any land ownership that has never been disputed because nobody objected due to the death of the original owner in the battle of Okinawa, threats by gangsters such as in the case of the old woman, or other reasons.

BTW, there was a vacant lot near the house of a sensei’s dojo where I lived. When I registered my Alien Registration Card, in 2011, I took the adress from Google Maps. Some time later, I was tending the Bar at the Seamen’s Club in Naha. Two Japanese persons came in whom I had never seen before. They were kind and talked to me to get an impression. They said, “Oh, chigau,” I guess because I am a nice guy. Then they showed their cards and they were from the immigration office on the mainland. The address I gave was the vacant lot, not sensei’s house.

I explained everything to the officers and admitted that it was solely my fault. They told me to go to Tomigusuku City Office and have it corrected, which I did, and so the matter was solved.

© 2023, Andreas Quast. All rights reserved.