There is a terminological double-issue related to the periodization in Japanese budō. The first and main issue is the ambiguous definition of old vs modern schools using the Meiji restoration of 1868 as the reference point. The second issue is that the same concept is used for Okinawa.

As regards periodization in Japan, in 1903, a comprehensive division of Japanese history was begun to be established by applying Western history studies. The English history term “modern age” was translated as kinsei 近世 to be used for the Edo period, and this was used as the basis from which all other eras were labelled. Literally, kinsei means “modernity,” or “modern era.” However, today’s modernity is tomorrow’s past. Therefore, seen from today’s perspective, kinsei should be understood to mean “early modern era.” While definitions vary, “early modern Japan” here is defined from the Azuchi-Momoyama period to the end of the Edo period (1574–1868).

By translating the English historical word “Middle Ages,” the period before the Edo period was labelled kinsei 中世, or “medieval era.” Furthermore, the period before the medieval era was collectively labelled as kodai 古代 or antiquity. Like this, modern periodization of Japanese history was first established by using a three-era-division based on Western history.

Because this division didn’t capture Japanese history well, with ongoing times, kindai 近代 was added thereafter. Kindai literally means “modernity,” “early modern era,” or “present.” From today’s perspective, the word kindai also refers to “an era before the current political system and the era of the international community.” That is, kindai is the period from 1868 until the end of World War II (1945).

This is followed by gendai 現代, or the contemporary era. It refers to the era of the current political system, which has been stable since 1945.

From this, the historical periodization of Japanese history is roughly as follows.

- Prehistory (senshi 先史): Until the invention of writing systems.

- Antiquity (kodai 古代): Jōmon period to the Heian period (ca. 14000-1185)

- Middle Ages (chūsei 中世): Late 11th to the late 16th century.

- Early modern period (kinsei 近世): ca. 1574–1868.

- Late modern period (kindai 近代): 1868–1945

- Contemporary period (gendai 現代): 1945 – today

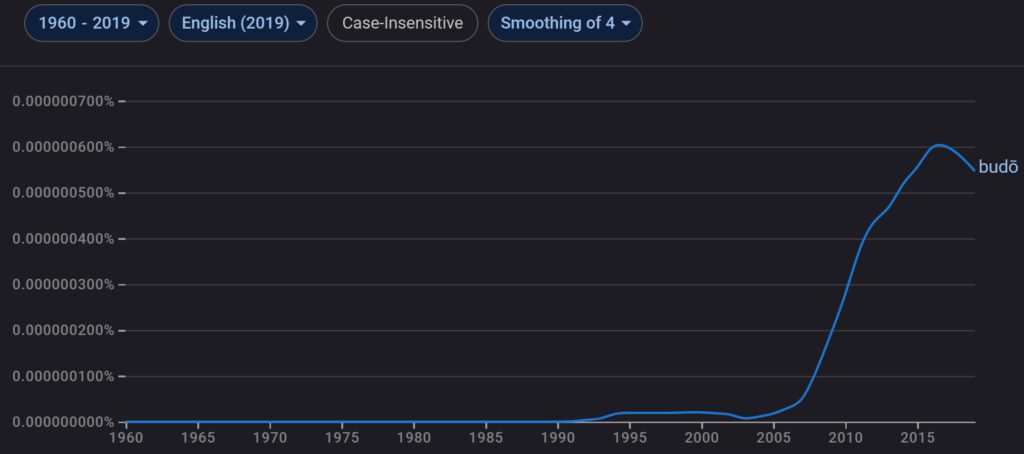

As indicated above, between kindai and gendai, there was a change in the political system, and this had a major impact on budō. During kindai, budō was also developed as a combat technique and for indoctrination in what can be termed a militaristic and depending on the author even fascist Japan, which during gendai has been purged. During gendai, revived kendō, along with jūdō and sumō, was reborn under the new term kakugi, an umbrella term for combat sports. This is because the revision of the junior high school government curriculum guidelines of 1958 prohibited the use of the word budō when classifying exercise forms. The term kakugi was only changed to budō in 1989 due to revisions to the guidelines of the Ministry of Education. A little earlier, in 1987, the Japanese Budo Association (Nihon Budō Kyōgikai) established the Budō Charter representing the new definition of budō of the ten member federations of Judo, Kendo, Kyudo, Sumo, Karatedo, Aikikai, Shorinji Kempo, Naginata, Jukendo, amd the Nippon Budokan Foundation.

In short, while based on older methods, gendai budō was formally established only in the 1980s and is inherently different from budō of the “late modern period” (1868–1945), which in turn was also inherently different from even older methods from the “early modern period” (1574–1868). So, there was as much continuity as there was disruption and transformation, and this is an important point that cannot be ignored.

As regards the second issue, while in Okinawa during kindai also all sorts of combat trench warfare spiritual kamikaze stuff entered karate and kobudō through school and young men’s corps in every village, it has never been purged after 1945, which is a difference to the mainland of Japan. Quite on the contrary, after 1945, it received affirmation under US rule for various reasons and today is the main export article of the prefecture. Many of the postwar trainers who have since passed away were involved in military style education of the militaristic era between 1930 and 1945, and this has never been questioned nor ever made the subject of discussion.

In short, while using various external markers identifying it as a contemporary Japanese gendai budō, the contemporary (gendai) Okinawan martial arts carried on several ideas, concepts, and techniques from the kindai budō era, which can easily be deduced from the names of young men who started training in the 1930s until 1945, and who became the main shidōsha or coaches after 1945. On Okinawa, these are considered kobudō or old-style methods, and maybe, within this periodization, much of Okinawan kobudō or old-style might in fact be kindai instead of koryū, which is another issue in itself, not to mention the invention of countless traditions under the name of kobudō during gendai. So, there are several undercurrents of misconceptions carried along all of this, nurtured and furthered by various stakeholders.

BTW, in Japanese Wikipedia, the term gendai budō doesn’t even exist. Also, the Japanese Kotobank dictionary does not have an individual entry of gendai budō in any of its referenced dictionaries. It seems therefore, that while the expression gendai budō might be used here and there in Japan, it is not an official term of the Japanese general language or any of its special languages. It seems more of a Western concept to somehow describe the complex evolution of budō in simplified terms and positive light.

In the end, Japan is a super sports country! The Japanese budō are amazing sports that are rooted and characterized by their historical and cultural connection, be it Japanese history in general or regional history in particular. However, the public discourse on the various budō and their relation indicate the necessity of a more careful use of the term gendai budō, its characterization, contents, and historical development.

Finally, as regards the periodization of Okinawa Prefecture, the era between 1879 and 1945 should be labelled in English as “early modern Okinawa,” which immediately shows the difficulties in comparing it with the corresponding periodization of the “late modern period” (1868–1945) of Japan in general.

© 2023, Andreas Quast. All rights reserved.