Typically, most members of the karate community oppose or even forbid discussion of certain topics. For instance, the topic of the involvement of Okinawan karate people in Japanese imperialism, colonialism, and militarism until the surrender in 1945 is carefully and cautiously circumnavigated. The reason is simple: It does not fit into the modern narrative of the peaceful kingdom. Also, why would Okinawans demonstrate against US bases if they had been so much “emotionally invested in the project of Japanese nationalism and militarism,” at least when they were young and until 1945? The same topic also diametrically opposes karate’s spiritually and philosophically draped self-portrayal.

In connection with Okinawa, a certain group compulsion towards positivism (a form of extremism) can also be seen as such, which is already strongly reminiscent of ideology, but it would probably be going too far to try to recognize people with a penchant for ideologies in all Okinawa fans.

For instance, it is common to praise Okinawa soba (noodle soup) and other foods in the highest tones, even if it is just a noodle soup. Another good example is Awamori, the indigenous spirit: Once used to clean corpses of flesh residue etc. after seven years in a bone urn, it is now extremely popular as a lifestyle party drink.

It is not exactly known where all these ideas-turned-ideologies came from but there have been varied reactions to a recent short post of mine on social media. It was a short quote from an article by Sayaka Chatani of the National University of Singapore. Chatani has clarified in a groundbreaking study “how and why young men in rural areas of Japan … became emotionally invested in the project of Japanese nationalism and militarism,” and this is very true for Okinawa as well for the time from about 1895 to 1945, that is, half a century.

In one of her texts, Chatani stated as follows:

“The imperial government invested more resources in ruling and establishing large-scale industries in Taiwan and Korea. Whereas spectacles of urban modernity in Taipei and Seoul impressed visitors, Okinawa’s capital, Naha, suffered the notoriety of having massive red-light districts, a manifestation of ‘barbaric’ old customs from the viewpoint of social reformers.” (Ōta 1995:279–289; Cf. Chatani 2018)

Let’s take a look at a rather unknown side of such “barbaric old customs.” To do so, we look at the genealogy of the Chō-clan. One of the houses of this clan was newly established in Naha as a non-hereditary house, but in the 3rd generation they achieved hereditary status as a house of Naha samurē. In this family lineage the first character of the personal name of the sons (nanori-gashira) was henceforth Sei 盛. Typical family names among the extended family circle (monchū) are Takemura and Nakamura.

One episode of the extended family relates to the family members from Itoman. After the rural village had been ruined by natural disaster, the boys and girls of the farm village were sold into peonage one after another. This is referred to by the saying “With the girls sold as prostitutes and the boys sold as Buddhist priests, Itoman itself was de facto sold out.” The children became indentured servants: The girls in the red-light district of Tsuji, and the boys as child monks in temples, or as fishermen in Itoman.

There were three red-light districts in Naha during the Ryūkyū Kingdom era, namely Tsuji, Nakashima, and Watanji. Tsuji was located in the western part of Naha and bordered to Kume village. Tsuji Village as a whole was a special village called a licensed red-light district (yūkaku). Nakashima was located in the southeastern part of Naha and belonged to Izumizaki Village. Originally located on a sandbank, it used to be connected to Izumizaki by a bridge. Watanji was a small island located in the southeastern part of Naha, facing Naha Harbor to the south, east and west. It belonged to Higashi Village and was connected to it by the Shian Bridge.

Naha was a port town for hundreds of years, so it is thought that prostitutes have lived there since ancient times. Then, in 1672, all prostitutes were gathered and placed under the control of the Ryūkyū royal government, and the red-light districts of Tsuji and Nakashima were established. It is unknown when Watanji red-light districts was established, but in 1908, the Nakashima and Watanji red-light districts were abolished and integrated into the Tsuji red-light district by Okinawa prefectural ordinance.

Asahi Shinbun Digital

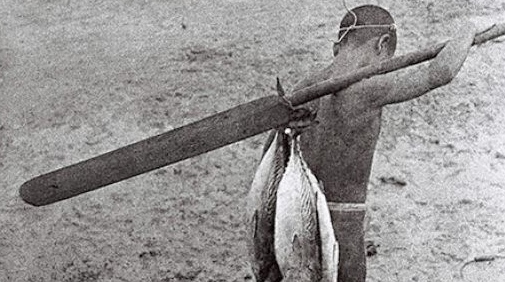

Recently a number of photographs were discovered. Among others, a photo shows a fishing boy with an uēku (paddle) in the Itoman area. Many fishing boys at the time were in indentured servitude as a “hired child” who lived and provided labor to a shipowner for about 10 years after the age of 10. These were not only boys, but also girls. Ueda Fujio (74), emeritus professor at Okinawa University who is familiar with this issue, said, “In modern times, this is a violation of human rights, but at that time (1935) it was considered superior to other systems of selling oneself (into bondage, esp. for prostitutes).”

In short, from the Ryūkyū kingdom era up until the early 1940s, children in Okinawa were sold into prostitution, indentured servitude, peonage, child labour, etc. for centuries. The girls were mainly sold to the massive red-light districts of Tsuji etc., and the boys were mainly sold as child monks to temples, or as fishermen to Itoman. Such were the “old customs” that were considered barbaric from the viewpoint of social reformers.

The Tsuji red-light district only disappeared with the end of World War II.

© 2022, Andreas Quast. All rights reserved.