The following article is based on a chapter first published in my work “Karate 1.0” (2013).

The Hiki of Old Ryūkyū

A term of interest frequently appears in historical sources of the Ryūkyū Kingdom. It is the term Hiki ヒキ(引). The concept of Hiki was widely distributed throughout the three adjacent areas of the Amami, Okinawa, and Sakishima Islands and attracted attention in anthropology and folklore studies. Discussion about its character as a royal guard and their official titles as seen in inscriptions and other historical sources can be found in the writings of Iha Fuyū, Nakahara Zenchū, Tomiyama Kazuyuki, Takara Kurayoshi, as well as in the Okinawa Daihyakka Jiten.

The original meaning of Hiki is that of relatives following a paternal family lineage (Cf. Makishi 2012: 171). It is considered a concept related to organizational principles of groups such as tribes, groups based on consanguinity (ketsuen shudan 血縁集団, zokuen 族縁,), kinship groups (shinzoku kankei 親族関係, also shinzoku shūdan 親族集団), religious groups (saishi shūdan 祭祀集団), etc. In Ryūkyūan history we may see this system developing from the early Makyo communities to the Mura villages, districts, further to the Gusuku castle communities, and finally to the Ryūkyū Kingdom.

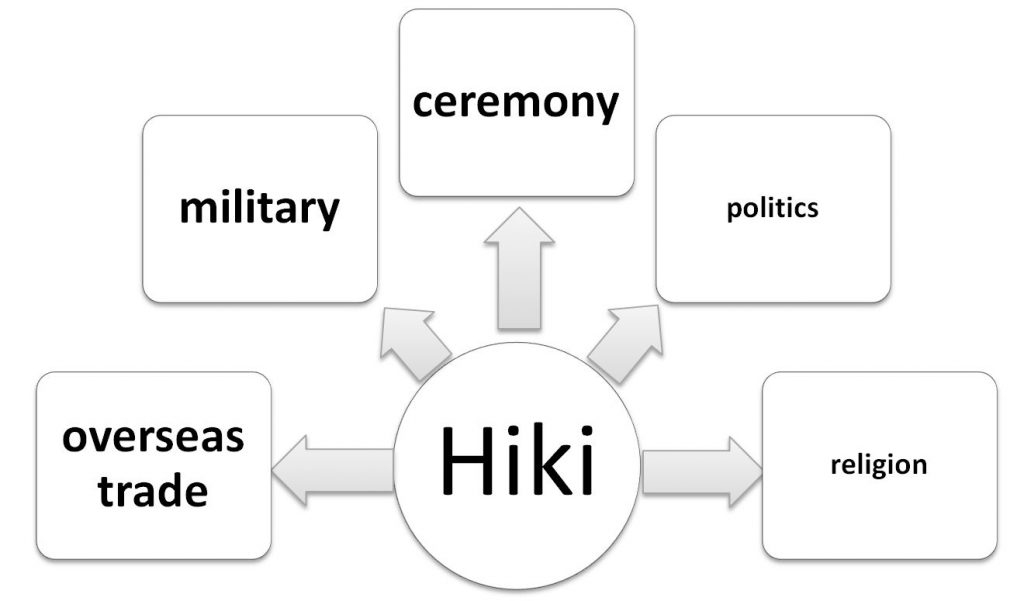

The Hiki in question here particularly refer to the royal government organization of the Ryūkyū Kingdom characterized by the organic combination of duties related to politics, overseas trade, ceremony, and military (Cf. Okamoto, in Acta Asiatica 2008: 55. Takara 1993, I: 102. Smits 2010).

The Hiki played a fundamental role in Ryūkyūan international maritime trade as well as religious ceremonies related to it. Examples can be seen in rituals performed just prior the departures of maritime vessels, when hawsers for the China-bound vessels were produced inside the royal castle in Shuri, accompanied by chanting of divine royal songs. On such occasions, the high priestess called Ōamu 大アム would perform rites at Naha harbor in which the boatman, the rope officials, the craftsmen, the general manager and other members of the crew participated (Makishi 2012: 172, 183). Furthermore, the Hiki also played a fundamental part during the ceremony called “Three Things” (monomairi 物参り, that is, the rice ceremony, the harvest festival, and the ritual rainmaking prayers performed in the royal castle in Shuri, accompanied by dancing, and strongly related to the sorcery-like nature of the Omoro ballads.

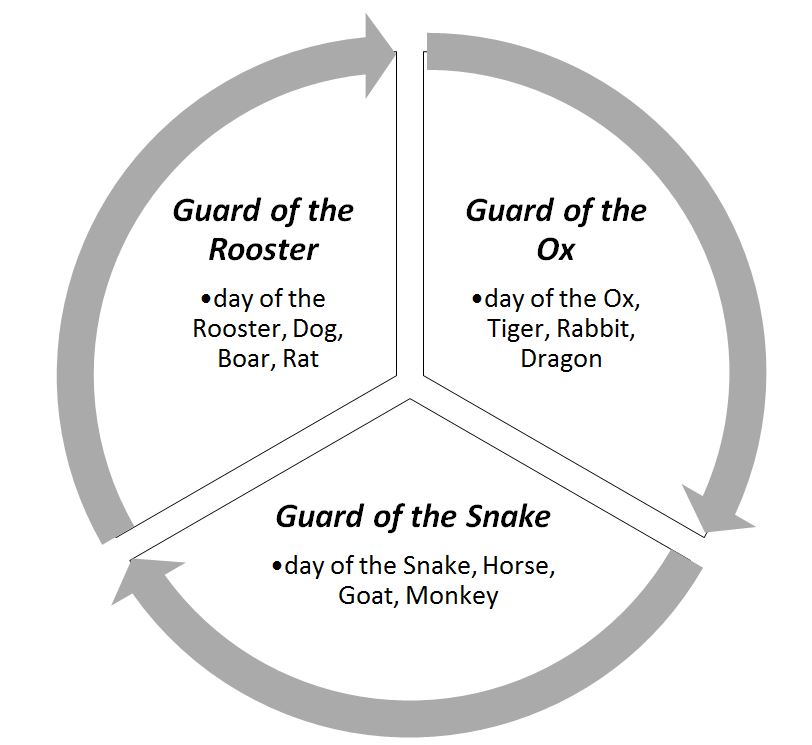

Figure 1: The Cycle of Consecutive Days of the Three Guards

Furthermore, according to inscriptions and other historical records, the Hiki also participated in civil engineering works inside and outside the royal castle. For instance, Hiki were deployed for the maintenance of the road approaching the Benzaiten-dō 弁財天堂 shrine on Bendake 弁嶽 peak, dedicated to Sarasvati, an Indian river goddess (Makishi 2012: 172-73, referring to the Katanohana Hibun かたのはな碑文).

During the time of King Shō Sei (尚清, rg. 1527-1555), historical sources indicate that the Hiki were directly involved in all kinds of production, crafts and the like outside the royal castle as well as in the construction of Yarazamori fort in the entrance of Naha Harbor and other construction projects. Moreover, Hiki also acted as attendants, as the royal gate- (monban 門番) and bodyguards (jiei 侍衛) who, in case of emergency, would become soldiers (Makishi 2012: 172). Or, as Takara Kurayoshi put it:

The Hiki were networks into which the Ryūkyūan upper classes were incorporated for the purposes of military, police, and guard service and other duties.

Takara 1994-95: 3

Sea-going Hiki

Each Hiki was referred to by a unique name, such as Jakunitomi or Sejiaratomi etc. The original nature of the Hiki is connected to the eulogistic suffix -tomi (富, sometimes addressed as 豊見), a shortened form which originally meant “to become famous or renowned,” or “to achieve fame” (Takara 1993, I: 108-10). In Old Ryūkyū it was used as a eulogistic suffix for large seagoing vessels. And all the Hiki also bear such ship names and the eulogistic suffix, too. This can be seen, for example, in the oldest known written appointment (jireisho 辞令書) in existence, dated 1523/08/28:

The following statement is an order by the king. The person Shiotarumoi, who belongs to the Seiyaritomi Hiki, is appointed to the post of Kansha (warehouse manager) aboard the (tribute ship) Takara-maru, which will soon set sail for China. This writ of appointment is presented by the king to the above-mentioned Shiotarumoi.

Takara, The Ryukyuanist, No. 27, 1994-95: 3

Further examples are the “Written Appointment of the Captain of the China-bound Vessel ‘Yotsugitomi’ 世次富 (1537) and the “Written Appointment to the Position of Adjudant of the Southeast Asia-bound Vessel ‘Sejiaratomi’ 勢治荒富 (1541)” (Cf. Takara 1993, I: 110).

The suffix -tomi as a designation for large seagoing vessels also appears in the collection of ancient prose called Omoro-sōshi (おもろさうし), for example in the Kakuratoyotega-bushi (かくらとよてがふし) from Omoro-sōshi Vol. 3. In this Omoro are found the terms Yohikitomi (世引富), Sejiaratomi (勢治荒富), Yotsugitomi (世次富), Kumokotomi (雲子富), Amaetomi (安舞富), and Oshiaketomi (押明富). All of these were names of Ryūkyūan seagoing vessels. This specific Omoro is meant as a divine song and the suffix -tomi was probably assigned on occasion of religious ceremonies as a prayer to the sea-gods for safe voyages performed by the Kikoe Ōgimi (聞得大君, high priestess in the organization of rituals and holy women) or any top-level holy woman. In the Omoro-sōshi, many prayers for safe navigation are encased and it appears to always have been necessary to recite the eulogistic suffix -tomi for divine help. In Omoro-sōshi Vol. 13 it is noted that on the 25th day of the 11th month 1517, when the Sejiaratomi put to sea towards Southeast Asia, none less than King Shō Shin (尚真王, rg 1477-1527) himself recited this Omoro. Here again, without a doubt, Sejiaratomi is the name of the ship. Twenty-four such ship-names compiled from among the Omoro-sōshi are given in Takara 1993, I: 113.

Maritime-based and Land-based Hiki

Iha Fuyū stated,

“Because foreign trade voyages were at the center of the activities of the people of Old Ryūkyū, we realize that the Sentō 船頭 (captains) steering these vessels were diverted from their original intended duty.”

Iha 1975: 292

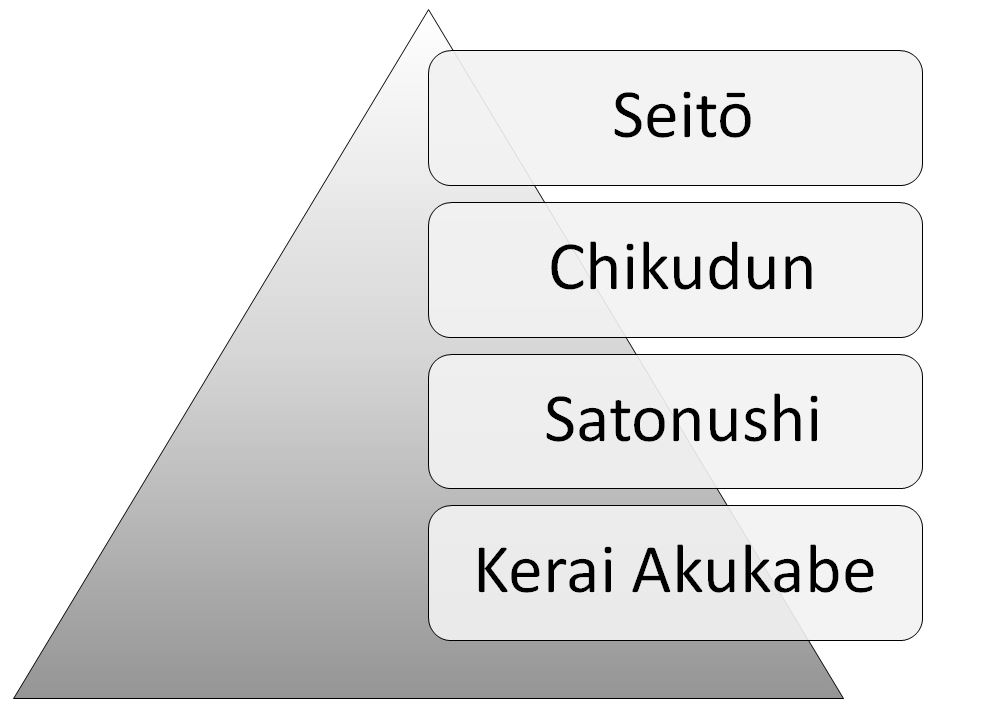

Indeed, the designations of seagoing vessels and the official posts associated with it coincide with those of the land-based Hiki (Okamoto, in Acta Asiatica 2008: 55). Consequently, the land-based Hiki had the same standardized office organization as the organization of the sea-going vessels. From there, Takara formulated that, perhaps, the land-based Hiki must be considered “land-based maritime vessels” (chijō no kaisen 地上の海船) while the vessels must be considered “Hiki floating on the sea” (umi ni ukanda hiki 海に浮んだヒキ): Just as sea-going vessels would sail in a fleet comprising of several ships, the Hiki were also organized in groups consisting of a number of Hiki. And just as the ship with the chief tribute envoy as its commander was the flagship of a fleet, the Hiki with the commanding Hikigashira 引頭 was the “flagship” in each of the “three guards” (sanban 三番) of the organization, i.e. Ushinohiban, Minohiban, and Torinohiban (Takara 1993, I: 114-115). The term Hikigashira had been described in the Ryūkyū-kuni Yuraiki (琉球国由来記) of 1713: While each Hiki had one commander (seitō), each group of three Hiki had one leading Hiki, which was marked by the Hikigashira.

At the time this system emerged, the king was on top of the country’s official overseas trade, which was solely managed by the royal government, and therefore, the envoys’ ships were all government-owned ships. All posts in this official overseas traffic were also issued in the name of the king, as is clearly shown in the kingdom’s written appointments (jireisho). Consequently, all crew members were employees of the royal government. In this way, all activities in the country of destination were government businesses, too. And so, regardless of being sailing voyages or land-based duties, any of the activities the Hiki were involved in were government businesses. This was the state of affairs, and it was in this framework that the system of the Hiki originated (Takara 1993, I: 115).

Figure 3: The Hiki as a maritime and land-based organization

Duties within the Hiki

Corresponding to the interchangeable nature of sea-going vessels and land-based Hiki, the posts of both of these are also comparable and merged at some point. The term Sentō 船頭 used for the captains of the sea-going vessels is a good example. Over time it came to be written in Hiragana simply as Sedo, and eventually it came to be written with the characters Seitō (勢頭, Oki.: Sīdu シードゥ). Seitō were the leading military officers of the Hiki organization under the Old Ryūkyū royal government. It was a term generally used by subordinates denoting a leader. As described in “The Duty of the Seitō” 勢頭役, in Volume 2 of the Ryūkyū-kuni Yuraiki (1713). In other words, the terms Sentō and Seitō describe the same thing.

Although it is unknown when exactly the organization of offices was begun, there were twelve Hiki in Old Ryūkyū, each of which was led by one Seitō as the commander, and one subordinate official or adjudant called Chikudun 筑殿 (Kyūyō, article 155; Ryūkyū-kuni Yuraiki 1713; Takara 1993, I: 105; Iha 1962: 53-54), which in turn were chosen from among the low-ranking soldiers called Kerai Akukabe 家来赤頭 (as noted in the Yarazamori Inscription).

It has further been established that the Seitō duty was held by Ōyakomoi (大屋子もい, lit. petty landowner; the later Pēchin) class officers and that the Hiki organization possessed Satonushi (里主, lit. lord of a village) offices for the regional governance on district level (See the table given in Takara 1993, I: 122 and the respective explanations). Furthermore, local officials called Okite served on the village level and extended all over the Ryūkyū kingdom up to the Amami region. That is, the Hiki were organized through offices and representatives in all regions throughout the kingdom. Therefore, the original Hiki can be reconstructed as follows.

The Military Nature of the Hiki

As regards the military nature of the Hiki, Iha Fuyū touched the defense system of Shuri Castle and Naha Harbor, that is, the two facilities with the most crucial function for the kingdom, notes on which are scattered here and there in inscriptions. Iha explicitly noted that the Yo-asutabe (世あすたべ, the later sanshikan 三司官) served as the directors of the “Three Guards” and held command over the country’s armed forces. He further stated that the operational level of the military was mainly carried out by the Hiki organized under the “Three Guards.” Nakahara Zenchū presented the officers of Shuri Castle’s security guards (keibishi 警備士) as part of the Hiki, and interpreted the inscriptions in much the same way as Iha, expressing his opinion that the Hiki were the nucleus of the kingdom’s system of national defense (Nakahara Zenchū Zenshū, Vol. 2, 1977).

Indeed, in inscriptions of Old Ryūkyū appear descriptions of guards (ban 番, lit. guards; an organized system of offices) that were organized into a defense system. The members of these Hiki were provided with implements of war by the government (Makishi 2012: 162), with the total number of the army generally estimated to 3000 troops under the leaders of the Hiki (Kyūyō, article 159. See also the works of Beillevaire, Uehara, Takara, et passim). In this, Takara saw a confirmation of an actually military character of the kingdom (Takara 1993, I: 117). Furthermore, as Okamoto pointed out, the inherent military character of the Hiki as observed by Takara, based on the theories of Iha Fuyū and Nakahara Zenchū, is of course very likely, as Ryūkyū’s seagoing vessels fundamentally originated in the military organization of the Ming’s Imperial Navy and coastal defense system (Takara 1993, I: 117. Okamoto 2008: 232). As seagoing and land-based Hiki were equal and came into being by integral mutual feedback, the Ming’s maritime and coastal military organization of the era inevitably entered Ryūkyū’s government organization via the tributary relation from the latter half of the 14th century to the first half of the 16th century. Evidence can be seen in the ships Ryūkyū initially bought from China. These ships were 40 m long and 7 to 8 m in width, carrying 250 men, later up to 360 men (Kreiner 2001: 7). These were excellent Fuchuan junks, built by Fujian shipbuilders in the heavily guarded coastal province of Fujian and constituted the Ming navy’s main warship (Dean 1998). Therefore, due to the interchangeable nature of sea-going vessels and land-based Hiki, the Ming’s military organization must have become part of the government organization of Ryūkyū, albeit fragmentary.

Swords from royal possession related to the Hiki

In early modern Ryūkyū, in a long and complex process many of the old Hiki duties branched out and became something new, while fragments of their old characteristics also continued. There were even Hiki that survived until the end of the kingdom in the late 19th century. And there are artifacts handed down within the royal family until today that remind us of the Hiki and their long lasting history. These two artifacts apparently survived the blaze of Shuri Castle on early October 31, 2019 .

The Okinawa Churashima Foundation, which manages Shuri Castle, had fire-resistant storages in the “Nanden” and the “Yuinchi” buildings. While the buildings themselves burned down, it was revealed that everything in the fire-resistant storages remained intact.

The swords were stored in the fire-resistant storages of the “Yuinchi.”

This short sword was manufactured in the 16th century. Square mother-of-pearl pieces are affixed to the scabbard (saya 鞘) of this item, and the royal coat-of-arms arranged variously. On a small part there are also waterbirds, chrysanthemum and leaves. The character ten 天 (heaven) is engraved in sealscript on the wedge shaped metal collar (habaki 鎺). The character ten 天 (heaven) is also engraved on the ura-sides of the sword spyke (kōgai 笄) as well as on the handle of the small additional knife (kozuka 小柄), followed by the engraved word “Seiyaritomi” (せいやりとみ). In addition, this item’s bag is of gold-brocaded satin damask which is similar to the arabesque lotus pattern seen on the curtain on the posthumous portrait of King Shō Iku 尚育王 (rg. 1835-1847).

Character ten 天 (heaven) engraved on the sword spyke (kōgai 笄) and the small knife (kozuka 小柄), followed by the word “Seiyaritomi” (せいやりとみ).

Photo: Shurijo Castle Park

Character ten 天 (heaven) engraved in sealscript on the wedge shaped metal collar (habaki 鎺).

Photo: Shurijo Castle Park

As regards the swords held by the attendants, see the article by Motobu Naoki Sensei of the Motobu-ryu.

Seiyaritomi

According to the description, the handles of both the sword spyke (kōgai) and the additional knife (kozuka) are engraved with the word “Seiyaritomi” せいやりとみ. This refers to nothing else but the Seiyaritomi 勢遣富 Hiki.

The Seiyaritomi Hiki was the commanding Hiki of the Ushinohiban 丑日番 (Guard of the Day of the Ox), and it was also a name of a Ryūkyūan seagoing vessel to China. The name is found in the oldest known written appointment (jireisho) of Ryūkyū in existence, dated 1523/08/28:

The following statement is an order by the king. The person Shiotarumoi, who belongs to the Seiyaritomi Hiki, is appointed to the post of Kansha (warehouse manager) aboard the (tribute ship) Takara-maru, which will soon set sail for China. This writ of appointment is presented by the king to the above-mentioned Shiotarumoi.

Takara, The Ryukyuanist, No. 27, 1994-95: 3

The Ryūkyū-kuni Yuraiki (1713) lists the members of the Seiyaritomi Hiki in early modern times. Here we can actually see the transformation of the old military and security functions of the Hiki as follows:

- 1 Seitō 勢頭 (the highest commanding officer of the Guard of the Ox)

- 1 Chikudun 筑殿 (vice-commanders or adjutants of the Hiki)

- 2 Azana アザナ(阿佐那) (guards assigned to the two watchtowers situated in the east and west of Shuri castle, called Taka-azana 高アザナ and Shimasoe-azana 島添アザナ)

- 2 Chūmon 中門 (guards assigned to the intermediate gates of Shuri Castle)

- 11 Kerai Akukabe 家来赤頭 (low-ranking soldiers wearing a red Hachimaki) 1 Jōshōsha (permanent resident guards living in Shuri castle)

Apparently the Seiyaritomi was resolved around the end of the 17th century. The last entry I could find for an assignment to this Seiyaritomi Hiki is in the year 1696.

This short sword was manufactured between the 16th century and the first half of the 17th century. The scabbard has black lacquer sprinkled on it mixed with small shell pieces and coated with transparent lacquer that is polished. The wedge shaped metal collar (habaki 鎺) bears the comma-shaped royal coat-of-arms on both sides. On the ura-side of the sword spyke (kōgai 笄) mounted on the scabbard the character ten 天 (heaven) is engraved in sealscript. Below it is engraved the word Sejiaratomi せちあらとみ. On the handle of the additional small knife (kozuka 小柄), the name Monjushirō 文珠四郎 is engraved.

Character ten 天 (heaven) engraved in sealscript, followed by the word Sejiaratomi せちあらとみ.

Photo: Shurijo Castle Park

royal coat-of-arms on wedge shaped metal collar (habaki 鎺).

Photo: Shurijo Castle Park

Sejiaratomi

According to the description, the handle of the sword spyke (kōgai) bears the word “Sejiaratomi” せちあらとみ. This refers to nothing else but the Sejiaratomi 勢治荒富 Hiki.

For one, Sejiaratomi was the name of a Ryūkyūan seagoing vessel. Omoro-sōshi Vol. 13 notes that on the 25th day of the 11th month of 1517, the Sejiaratomi put to sea towards Southeast Asia. At that time, King Shō Shin himself recited this Omoro. Moreover, there is a written appointment (jireisho) from the year 1541: “Written Appointment to the Position of Adjudant (Chikudun) of the Southeast Asia-bound Vessel Sejiaratomi.”

Sejiaratomi was also the name of a Hiki. It was the leading Hiki of the Torinohiban 酉日番 (Guard of the Day of the Rooster). The Ryūkyū-kuni Yuraiki (1713) lists the members of the Sejiaratomi Hiki in early modern times. Here we can actually see the transformation of the old military and security functions of the Hiki as follows:

- 1 Seitō 勢頭 (the highest commanding officer of the Guard of the Rooster)

- 1 Chikudun 筑殿 (vice-commanders or adjutants of each Hiki)

- 4 Azana アザナ(阿佐那) (guard duty assigned to the two watchtowers situated in the east and west of Shuri castle, called Taka-azana and Shimasoe-azana)

- 1 Chūmon Seitō 中門勢頭 (commander of gate guards at the intermediate gates of Shuri Castle)

- 2 Chūmon 中門 (guards assigned to the intermediate gates of Shuri Castle)

- 14 Kerai Akukabe 家来赤頭 (low-ranking soldiers wearing a red Hachimaki)

The last entry for an assignment to the Sejiaratomi Hiki I was able to find was the year 1732.

Outro

The character ten 天 (heaven) was used to mark important items from the royal possession. This method was in use during the 16th to the early 17th century, probably only until 1609. The mountings (koshirae) of both above described swords were produced in Ryūkyū around that time.

According to the Kyūyō (Appendix Vol. I, No. 45), a certain Hokama from Wakasa in Naha went to Satsuma in 1644 and studied the method of honing sword blades for about three years before he returned home. Thereafter he received royal order to serve as “Chief Supervisor of honing sword blades” (migaki-gatana nushidori 磨刀主取). In other words, during the 17th century Ryūkyū there were artisans able to produce koshirae and to maintain sword blades.

What was the purpose of the above short swords?

Where they originally carried as weapons during sea voyages? Were they carried by the highest commanding officers (seitō) of the Hiki, either maritime or land-based? Were they used as status symbols? Were they lucky charms or did they hold some religiously charged powers for save sea journeys? Were they worn by the early modern highest commanding officers of the Hiki during guard duties at Shuri Castle?

The answer, and all that may be deduced from it, I leave up to you.

© 2019 – 2020, Andreas Quast. All rights reserved.