Ro Gai (Lu Jiangwei) (Joint Researcher, Research Institute attached to the Okinawa Prefectural University of Arts): Okinawa karate no kata meishō ni tsuite no ichikōsatsu (A Study on Okinawan Karate Kata Names). In: Ryūkyū Karate no Rūtsu wo saguru Jigyō – Chōsa Kenkyū Hōkokusho (Research and Study Report – Project to Explore the Roots of Ryūkyū Karate). Urasoe City Board of Education, March 2015. Pp. 81-87.

Translation: Andreas Quast

1. Introduction

In the past, the Okinawa karate was secretly carried out by a limited number of people as a martial arts “treasured and never shown in public” (mongai fushutsu), but after the abolition of Ryūkyū and establishment of Okinawa prefecture, it was gradually released to the public, especially since it has been incorporated into school education, including middle schools (1), in 1905. This has already been discussed in “Kindai Okinawa ‘Karate’ no Fukyū Hatten” (in: Okinawa Geijutsu no Kagaku, No. 23) (2) and “Meiji-ki no Okinawa karate no jishō ― gakkō kyōiku ni dōnyū mae no jirei o tōshite” (Events of Okinawa Karate in the Meiji period – through a case before it was introduced to school education. Published by the Okinawa Bunka Kyōkai Kōkai Kenkyū Happyōkai in 2013) (3). Since then, Okinawa karate has adopted various elements of the Japanese martial arts, such as manners, etiquette, dress, and the dan system, and has now spread throughout the world.

However, due to the lack of historical materials, there are many unclear points about the history of Okinawa karate. For example, most of the kata names of Okinawa karate are unclear (some are written in Chinese numeral characters, but most cannot be explained in terms of their names).

On the other hand, it is no exaggeration to say that the biggest difference between Okinawa karate and other Japanese budō is that it has systematized kata. Therefore, when considering the overall picture and roots of Okinawan karate, it is very important to identify the etymology of kata names in traditional Okinawan karate.

In this paper, I would like to consider the traditional kata names of Okinawa karate.

2. Characteristics of kata names of Okinawa karate

At present, there are Okinawan karate schools such as the Shōrin-ryū lineage, the Gōjū-ryū lineage, the Uechi-ryū lineage, and the Ryūei-ryū. There are also many different kata in each of these schools. (This is summarized in the Okinawa Daihyakka Jiten (4) and the Encyclopedia of Okinawa Karate Kobudō (2008) (5). At a first glance over the extant Okinawa karate, among all kata, there are some which are similar, while others represent a completely different variety of boxing. Therefore, it seems there are kata from many different varieties of boxing even in one school.

Regarding the origin of Okinawan karate kata, in the latter half of the Meiji era, Pinan Shodan to Godan were created by Itosu Ankō (1831-1915), but excluding kata brought directly from Fuzhou, China, such as “Sanchin,” “Sēsan,” and “Sandairu/Sansēryū” from the Uechi-ryū system, the origins of traditional kata handed down to what is called ‘ancient Okinawa’ are almost unintelligible. In addition, the kind of traditional kata names seem to have changed in a way that is different from the Japanese or Ryūkyūan language. In case of names represented by Chinese numerals, such as “18” (Sēpai), “24” (Nīsēshi), “28” (Nēpai), “54” (Ūsēshi), and “108” (Sūpārinpē), it is easy to understand that each designation corresponds to a Chinese numeral, but the other kata names that are expressed in the katakana notation are almost incomprehensible. Furthermore, since the introduction of Okinawa karate on the mainland of Japan, the kata designations written in katakana notation, whose meaning were originally unknown, have been assigned to kanji as a phonetic representation and regardless of the kanji’s meaning (ateji), making the names even more misleading.

Regarding the current status of the names of Okinawan karate kata, Kinjō Akio in his “Karate Denshin-roku: Denrai-shi to Genryū-gata” (6) stated the following:

“The kata names expressed in numerals showing the correct characters are names such as “Sanchin,” “13 steps” (Sēsan), “18 steps” (Sēpai), “24 steps” (Nīsēshī), “36 steps” (Sansēryū), “54 steps” (Ūsēshī), or “108 steps” (5), but in case of the names of the remaining forty or so kata, the correct pronunciation is lost due to the Okinawan dialect or the use of kanji as a mere phonetic equivalent (ateji).” (7)

Since the late 1960s, over the timespan of forty-one years, Kinjō Akio has traveled to mainland China and to Taiwan for more than one hundred-twenty-five times to explore the roots of Okinawa karate (8). As one of the results of this research, he wrote the aforementioned “Karate Denshin-roku.” The names of Okinawan karate kata are summarized in the chapter “Kata meishō no gengo kō” (Report on my investigation into kata designations)(9).

A total of twenty-four Okinawa karate kata are discussed in this chapter, namely:

- 11 kata of Naha-te-lineage: 1. Sanchin, 2. Tenshō, 3. Saifa, 4. Seisan, 5. Seipai, 6. Shisōchin, 7. Sanseiru, 8. Seiinchin, 9. Kururunfa, 10. Sūpārinpē, 11. Pechūrin,

- 8 kata of Shuri-te-lineage: Shuri Sanchin, 2. Naihanchi, 3. Shuri Seisan, 4. Passai, 5. Nīsēshī, 6. Ūsēshī, 7. Hakutsuru, 8. Kūsankū.

- 5 kata of Tomari-te-lineage: 1. Wanshū, 2. Wankan, 3. Rōhai, 4. Chintē, and 5. Chintō

In his “Report on my investigation into kata designations,” Kinjō Akio pointed out that the Fuzhou dialect and the Southern Min (Fujian) dialect of the Fujian language had a profound effect on the pronunciation of the names of Okinawa karate kata (which set the direction for future research on elucidating the kata names of Okinawa karate). However, Kinjō Akio investigated the pronunciation of the names of Okinawan karate kata in China via an interpreter, and it is not always possible to obtain the accurate pronunciation through an interpreter. In fact, Kinjō Akio said that he had a bitter experience with the issue of interpreting. (10) In order to find out how much the Fujian language affected the pronunciation of the names of Okinawan karate kata, it is necessary to compare the pronunciations of each kata once.

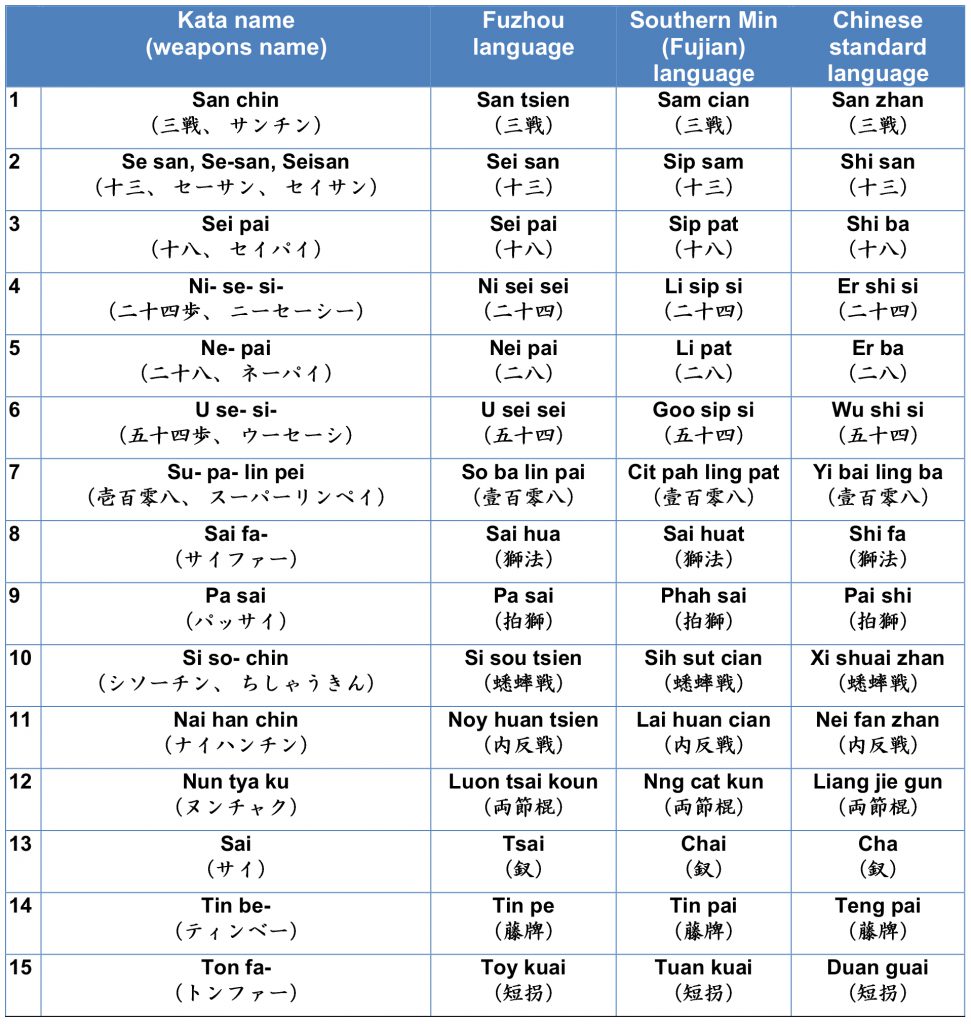

The following are Okinawan karate kata names (including weapons names) arranged in a list and with romanized Japanese letters.

Looking at the above list, kata names of Okinawa karate are clearly characterized by the fact that the pronunciation is closer to the Southern Min (Fujian) dialect or the Fuzhou dialect of the Fujian language, rather than to Chinese standard language. In addition, “Sanchin,” “Sēsan,” and “Nēpai” are still used as kata names in Fujian kenpō.

However, in order to identify the origin of the kata names of Okinawa Karate, and to determine the variety of kenpō the kata is from, it is not enough to consider the pronunciation of the kata name alone, but you also have to look at the movements of the kata.

Therefore, next I would like to consider each kata of Okinawa karate, both in terms of pronunciation of its name and its movement.

1. About “Passai”

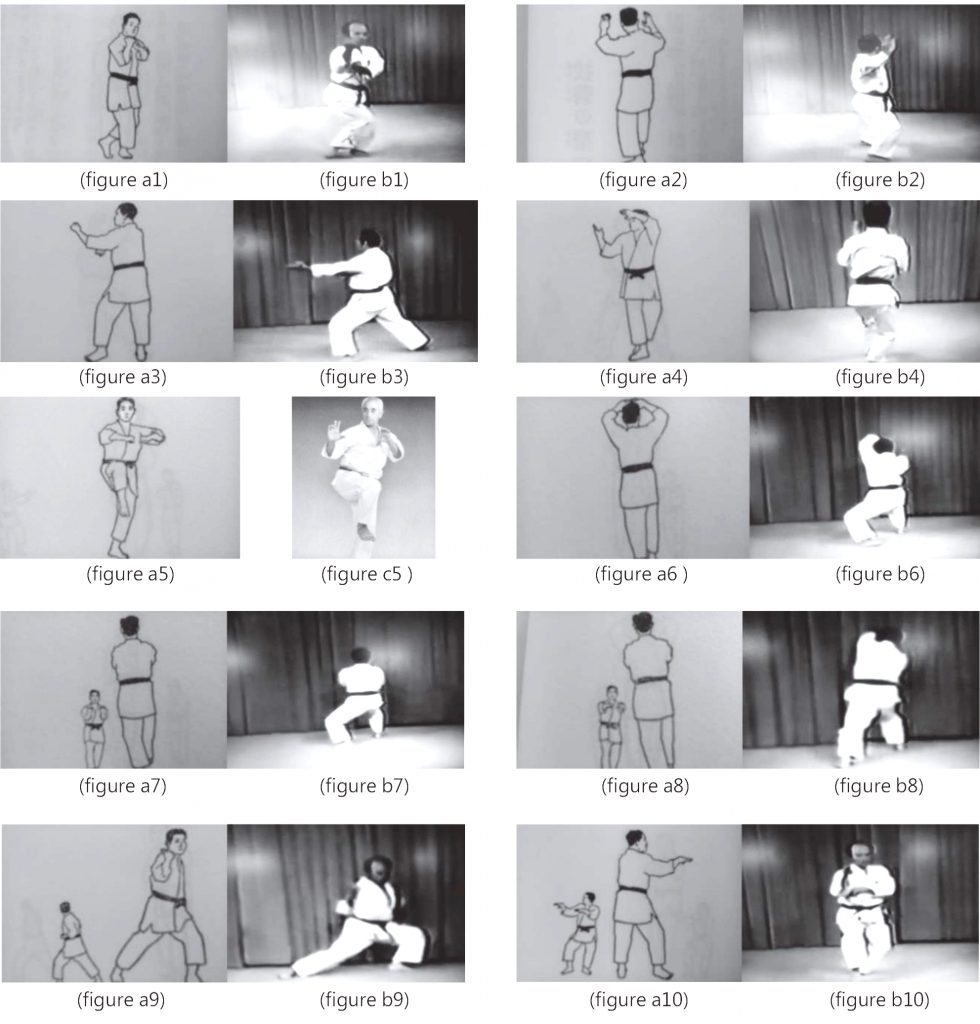

(Due to space limitations, this paper will only deal with the kata called “Passai.” Figures “a” are from the “Karate-dō Taikan” (11), figures “b” are from this video, and figures “c” are from the “Okinawa Karate Kobudō Jiten (Encyclopedia of Okinawa Karate Kobudō, 2008).

The kata “Passai” is considered to be one of the traditional kata of the Shōrin-ryū-lineage (including Kobayashi-ryū, Matsubayashi-ryū, and Shōrinji-ryū). At present, there are also designations such as “Tomari Passai,” “Matsumura Passai,” and “Itosu Passai,” which are relatively similar. For example, in the first movement (figure a1 and b1), there is a block (uke) while stepping into the cross-legged-stance (kosa-dachi), but there is a difference whether or not the block is supported by the other hand. The second movement (figure a2, b2) has the “yama (mountain) shape” posture, but differs in whether the right foot or the left foot is being forward. In addition, similar techniques are included, such as “chūdan yoko-uke” (mid-level horizontal reception), “kagite-uke” (hook-hand block), “morote-age-uke” (both-handed rising block), and “morote uchi-komi” (both-handed strike). The kanji notation of the kata name uses characters such as “抜砦” and “抜塞.”

The name of “Passai” can be found in an article in “Ryūkyū Kyōiku” on the “The Haraguni Incident” (12) that occurred on 1896-02-27 (1896-01-15 according to the old lunar calendar). In addition, 1938, Chibana Chōshin (1885-1969) stated, “There are two types of Passai, the one from the Matsumura school and the one from the Itosu school. From among these two, I would like to explain here the kata of the Matsumura school. I was taught this kata by Mr. Tawada. The Passai handed down by my former teacher, Itosu Sensei, I devote at another occasion.” (13) From that it is already clear that different kinds of Passai existed already in the 1930s.

Kinjō Akio has been investigating the origin of “Passai” in China for many years, and in his book “Karate Denshin-roku: Denrai-shi to Genryū-gata,” he has developed his theory mainly in terms of both 1. pronunciation and 2. movement. His final conclusion is that “Passai” may have come from “Baoshi” (豹獅, “leopard lion”).

Here (and while maintaining great respect to Kinjō Sensei’s research and study), I’d like to verify if this is really the case.

First of all, as regards 1. pronunciation, Kinjō wrote as follows:

“In the Fuzhou dialect of Fujian Province, “leopard” is called “bāh” and in Quanzhou dialect it is called “pau.”

And “lion” is called “sai” in both the Fuzhou and Quanzhou dialects. So “leopard lion” is called “Bāssai” in Fuzhou dialect, and “Pausai” in Quanzhou dialect.

In other words, Shuri-te Passai is a pronunciation of either Fuzhou or Quanzhou pronunciation, such as “leopard lion battle,” and I think that it may have been called “Passai” in Okinawan dialect, which became established.” (14)

As mentioned above, Kinjō gives the phonetic notation of “leopard lion” in the Fuzhou and Quanzhou (Southern Min) dialects in katakana, but when this is converted to Roman notation, “Bāssai (バーッサイ)” becomes “Ba-sai” and “Pausai (パウサイ)” becomes “Pausai.”

However, as indicated by Mr. Kinjō, in Fujian, the pronunciation of “leopard lion” is indeed “Pausai” in the Quanzhou (Southern Min) dialect. However, in the Fuzhou dialect, it is not “Ba-sai,” but also “Pausai” (same notation as in Southern Min language, but with a slightly different accent).

As regards the analysis of point 2. or “movement,” Mr. Kinjō picked the “first movement” and the “second movement” of “Passai” and describes them as expressions of the characteristics of both “leopard boxing” and “lion boxing,” respectively.

The “first movement” of “Passai” is the receiving movement (figure a1, b1) when stepping in. The “second movement” is the movement of receiving in “yama (mountain) shape” (figure a2 and b2).

In “Passai,” there are several movements that seem to be “lion boxing” (details will be described later). However, even if the“ first movement” is a characteristic of “leopard boxing” as pointed out by Mr. Kinjō, when you look at the entire “Passai,” there is not even a fist gripping method (similar to hiraken of Okinawa karate), no thrust or jumping movements that are unique to “leopard fist.”

Mr. Kinjō concludes that “Passai” might be a “leopard lion” style, but in terms of movement, as mentioned above there is no typical gripping, thrusting, and jumping of unique to “leopard fist.” Also, besides the “first movement,” he mentions no other action to be “leopard fist.” Combined with the pronunciation issue mentioned above, “Passai” seems to have a very narrow chance to be “leopard boxing.”

So where does the word “Passai” come from? Research so far in Fujian has revealed something that fits perfectly. Namely, the lion dance, which is called “Pa sai 拍獅” in Fuzhou and Quanzhou (Southern Fujian) dialects. (About lion dance, “wushi 舞獅” is a common term used for it in China, but there are several different and unique names in the regions. For example, it is called “醒獅” in Guangdong and Taiwan regions, and “拍獅” in the Fuzhou and Quanzhou regions. And, until a long time ago, village martial arts groups were in charge of lion dances in the Fujian region. Therefore, lion dance were more of a martial arts than a performing arts.) The reasons are listed below.

Pronunciation

The Romanized notation for “パッサイ” is “Pa sai.” In Fuzhou dialect, “lion dance (拍獅)” is “Pa sai,” and in Quanzhou (Southern Fujian) dialect, it is “Phah sai.” On the other hand, in standard Chinese language, it is “Pai shi.” The pronunciation of “lion dance (拍獅)” in Fuzhou dialect as “Pa sai” and in Quanzhou dialect as “Phah sai” is more appropriate to “Pa sai” (Passai) than the standard Chinese language pronunciation of “Pai shi.”

Movements

(Actually, it would be easier to understand it by using video, but unfortunately, it is not possible in paper format.)

The first movement (figure A1, B1), and the next movement of the receiving while stepping into the cross-legged stance. It has not yet been found which technique of “lion boxing” applies to this movement. However, the posture of the beginning of a lion dance (before the person in charge takes the lion head) is reminiscent of this behavior.

The second movement (figure a2, b2) is the “yama (mountain) shape” movement. This movement applies to the technique of “lion opens its mouth wide” (i.e. the salute at the beginning) of “lion boxing.” At the time of the lion dance, the posture before the person in charge holds the lion head, is reminiscent of this behavior.

Knock down and thrust movements (figure a3, b3). This movement is repeatedly performed in “Passai.” This applies to the technique called “gold lion inserts arrow” of “lion boxing.” In the lion dance, the postures of the lion playing the ball from side to side is reminiscent of this behavior.

The ura-uke movement (figure a4, b4). This movement applies to the “chopping arm” technique of “lion boxing.” In the lion dance, the postures of the person in charge of the lion shaking the lion sideways is reminiscent of this behavior. However, this movement is often seen in other kata of “Shōrin-ryū” lineage, so it may not necessarily be a movement of “lion boxing.”

Pulling and kicking movement (figure a5 and c5). This behavior applies to the technique of “plucking the ball gesture” of “lion boxing.” In the lion dance, the postures of the lion holding a ball and playing with it is reminiscent of this movement.

The movement of both-handed rising block and both-handed strike (figure a6 and 7, b6 and 7). These two consecutive movements apply to the techniques of “lion boxing” called “golden lion looks to the sky” and “golden lion inserts double arrow.” In the lion dance, the postures of the lion raising and lowering his head and pushing it forward, and its playful appearance is reminiscent of this movement.

Stepping in with a both-handed mid-level thrust (figure eps a8, b8). This movement applies to the technique of “the sun and moon line up like jujubes” from “lion boxing.” In the lion dance, the posture in which the person in charge of the lion steps thrusts the lion forward while stepping forward is reminiscent of this behavior.

The movement of the mid-level yoko-uke while bending forward (figure a9, b9). This action applies to the technique of “lion boxing” called “horizontal block.” In the lion dance, the posture of the lion licking its foot (called “lion licking its foot”) is reminiscent of this behavior.

The movement of kagite-uke (hook-hand block) while standing in neko-ashi-dachi (figure a10 and b10). This operation applies to the technique of “lion’s mouth” of “lion boxing.” In the lion dance, the behavior of the lion guarding around is reminiscent of this behavior. This movement is frequently used in “Passai.”

In figure b10, while performing the kagite-uke (hook-hand block), with the rear leg of the neko-ashi-dachi as an axis, the front foot draws a semicircle. This movement is found in the lion dance, when the lion appears and vigilantly watches his surroundings. In addition, when considered from the martial arts elements, while blocking the opponent’s thrust with one hand, and while attacking the opponent’s neck and eyes with the other hand, you can defeat the opponent by hooking his feet by drawing a semicircle with your foot.

As mentioned above, “Passai” has many techniques such as the “lion opens its mouth wide” (the salute of lion boxing), “plucking-the-ball gesture,” “golden lion looks to the sky,” “golden lion inserts double arrow,” “horizontal block,” and “lion’s mouth,” which are unique boxing techniques of “lion boxing” as handed down in the Fujian region. Moreover, there are movements reminiscent of the lion dance, such as pushing the head out, licking the feet, and guarding around.

3. In Conclusion

For a long time, the origin of “Passai,” one of the traditional kata handed down in Okinawa karate, has not been clear. Kinjō Akio has been investigating the origin of “Passai” in China for many years. In his book, “Karate Denshin-roku” he mainly argues from 1. pronunciation (“Bāssai” in Fuzhou dialect or “Pausai” in Quanzhou dialect) and from 2. movement (the “first movement” is based on “leopard boxing,” and the “second movement” is based on “lion boxing”) and concluded that Passai may have come from “leopard lion.” However, as a result of the examination in this paper, it was found that although “Passai” includes elements of “lion boxing,” it turned out that it is very unlikely that it includes elements of “leopard boxing.” And when considering “Passai” in terms of both pronunciation and movement, it can be concluded that “Passai” of Okinawa karate comes from the term for “lion dance” (拍獅) of the Fujian language (Fuzhou and Quanzhou dialects). The reason is that in 1. pronunciation, “Passai” has the same pronunciation as “lion dance” in Fujian language (the Fuzhou and Quanzhou dialects). And in terms of 2. movements, “Passai” includes many techniques such as the “lion opens its mouth wide,” “plucking-the-ball gesture,” “golden lion looks to the sky,” “golden lion inserts double arrow,” “horizontal block,” and “lion’s mouth,” which are unique boxing types of “lion boxing” as handed down in the Fujian region. And there are movements reminiscent of the lion dance, such as the pushing out of the head, the licking of the feet, and the guarding around.

Like this, the name “Passai” from Okinawa karate comes from the word for “lion dance” in Fujian language (Fuzhou and Quanzhou dialects), and it seems to include elements of the unique kenpō of “lion boxing” handed down in the Fujian region. Therefore, the types of boxing techniques in “Passai” of Okinawa karate must have originally belonged to “lion boxing.” Gōjū-ryū’s “Saifā” must have belonged to “lion boxing,” too (“Saifā” is the Fujian language pronunciation of the of “lion method” and it includes techniques of “lion boxing”).

In Okinawa karate, in addition to the boxing variety of “lion boxing,” there are various other boxing varieties such as “crane boxing,” “dragon boxing,” “arhat (monk) boxing,” and “tiger boxing.” Looking over the current Okinawa karate, despite the fact that each of those boxing varieties is different, the style of expression in current Okinawa karate is almost uniform, and there are basically no movements (techniques) that express the characteristics of each of the (underlying) boxing varieties.

Taking “Passai” as an example, in Okinawa, there are distinctions such as “Tomari Passai,” “Matsumura Passai,” and “Itosu Passai.” Since the late Taishō (1912-1926) and Shōwa (1926-1989) eras, Okinawa karate has been introduced to the mainland of Japan, was further modified, and slightly different kata were created, such as “Passai Dai,” “Passai Shō,” and “Bassai.” Nevertheless, every kind of “Passai” includes the techniques of “lion boxing.” However, the meaning of the kata-name “Passai” as well as the original meanings of the movements included in “Passai” were unknown. Also unknown was how to make a fist, which is an original feature of “lion boxing,”and how to breathe when performing “lion boxing” was unknown, as well as the style of expression when performing. All these specifics have faded and the differences to other boxing varieties have become indistinguishable.

One of the major reasons why this has happened might be the introduction of Okinawa karate to the Shuri middle school in 1905, which was “organized in the form of gymnastics” (15). Another possible reason may be that Okinawan karate was introduced to mainland Japan, adopted to Japanese mainland customs, and adopted school (ryūha) names as if it ignored the differences in the underlying boxing varieties.

To incorporate kata of several different boxing varieties into one single school (ryūha) is rather essential, when considered from the martial arts perspective. However, when forgetting the boxing variety that each kata originally belonged to, the roots of that school (ryūha) are lost. In that sense, in order to determine the complete picture and roots of Okinawa karate, the etymology of the name and the boxing variety it originated from must be identified for each kata of Okinawa karate.

© 2020, Andreas Quast. All rights reserved.