The purpose of this article is to provide some information on the peculiarities of combat sports in ancient Egypt. Moreover, it is meant as a contextual resource for a comparative study for those who study both armed and unarmed Ryūkyūan martial arts. While it is true that at first glimpse the cultural and temporal distance between ancient Egypt and Ryūkyū could hardly be more remote, the superordinate common denominator and the macro level of both is readily found in cultural anthropology. The article therefore aims at contributing to the question of the origin of such practices in humankind rather than emphasizing that which differentiates, such as technical, cultural, geographical, or other clearly visible differences. For example, the use of paddles (uēku) is a trademark of modern Ryūkyūan martial arts. But it is preceded by the use of paddles in form of a combat sport in ancient Egypt by some 4.5 millenia. Likewise, unarmed grappling is found both in ancient Egypt as well as in Ryūkyūan martial arts. Like this, no more and no less, the article might provide a modified and broadened perspective on the primordial soup from which both Egyptian and Ryūkyūan combative arts received their share.

Combat Sports

Miniature sculpture of two wrestlers. Egypt.

Combat sport activities, that is, the competition of man against man according to binding rules, derives from an early stage in human history. This particular form of physical contest or confrontation can be accomplished using various weapons (swords, dagger, etc.) and equipment (shields, straps, etc.). It can also be carried out entirely without using such utensils, by using the hands, feet, and even the whole body itself as the actual weapons. The opponents by no means have to be equipped with identical weapons and equipment; it is also not excluded that an armed athlete competes against an opponent who only uses his bare hands to win. Combat sport disciplines are united in that they always follow established rules and principles that regulate the use of the weapons or in case of unarmed combat prescribe the manner of using the hands and feet. The rivals are unconditionally obliged to this set of rules and regulations, which – depending on the respective culture, discipline, and epoch – can exhibit quite different levels of complexity. Since in combative sport, as opposed to purely military conflict, the physical annihilation of the enemy is not intended (except for borderline cases), these rules serve to safeguard the very life and limb of the athletes.

The genre of combat sport is well demonstrated among all people of antiquity. In ancient Egypt it is found in four different forms: Grappling, stick fencing, pugilism, and water jousting.

Overview

The most important single combat sport in Ancient Egypt was grappling, that is, the single combat between equal opponents without manmade weapon and according to prescribed rules. In contrast to stick fencing or pugilism it is verified from the earliest history to the Ramesside period (ca. 1292 BC. until about 1070 BC.), without a greater temporal fracture in between. This is substantiated by partially excellently preserved and remarkably detailed documentation. Whereas grappling is also found in other early civilizations – although nowhere in a similar density – the stick fencing is only verified for Egypt. Also in contrast to grappling only comparatively few depictions are found for stick fencing. In addition, the period were stick fencing depictions occur is also very limited: The earliest references can be found in tombs from the second half of the 18th dynasty (about 1550 BC until 1292 BC), the latest on the picture-ostraca from Deir el-Medineh, the city of the “Necropolis artisans”, which can be dated to the final part of the Ramesside period. Both these disciplines, often depicted together in the pictorial relief decorations of temples and tombs, are enriched by a third, but only very rarely documented combat sport, namely pugilism. This kind of single combat, in which the striking power of the clenched fists is the decisive factor, gained greater importance only at a much later time, such as in ancient Greece. Pugilism or boxing in ancient Egypt leave us with a quite doubtful image. The number of evidences is extremely low and in addition the quality of the individual materials hardly allow for truly safe and unambiguous conclusions. Due to its combative nature the “ancient Egyptian water jousting” has also to be placed under the topic of combat sports as a fourth discipline. Broadly speaking, these were combative confrontations fought out between the crews of two papyrus rafts. In the course of these fights the punting poles, by which the clumsy watercrafts were usually propelled through the marshes, were transformed into sporting equipment.

From a chronological point of view sources on single combat sport in the ancient Egyptian civilization can be divided into two large groups:

- The grappling depictions from the Old and Middle Kingdom (about 2686 BC – 1650 BC), and

- the single combat depictions of grappling, stick fencing, and pugilism from the time of the New Kingdom (about 1550 BC. to 1070 BC.).

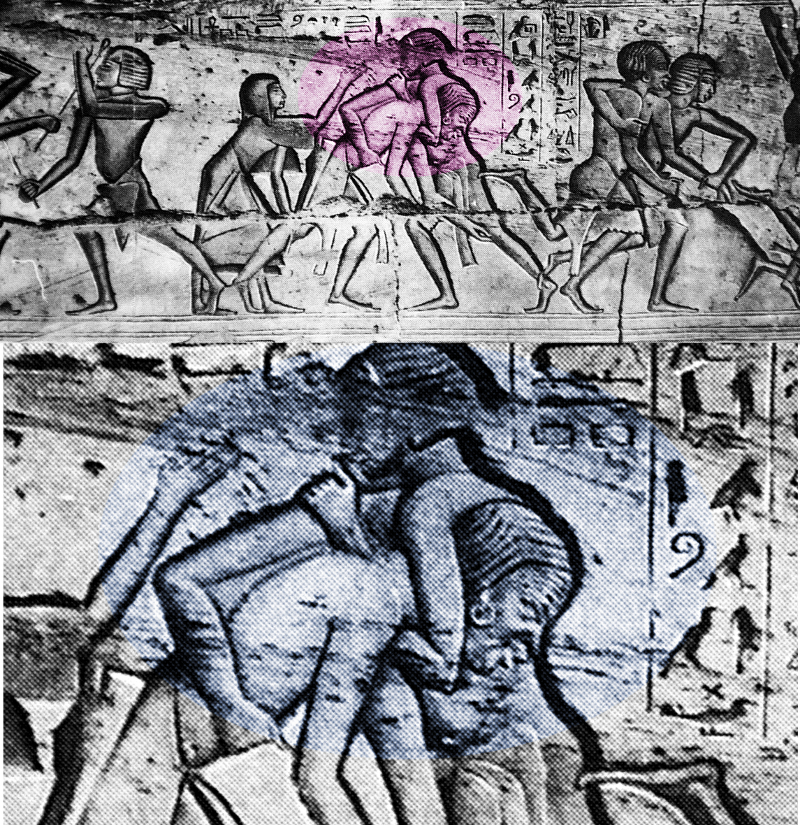

I. Grappling

The oldest depictions of grappling in ancient Egypt are found on the so-called “Libyan Palette” dated to about 3200 to 3000 BC, making it almost contemporaneous with the beginning of the historical era itself. From the era of the Old Kingdom (c. 2686 BC–c. 2181 BC) only one safe evidence exists until now. It is a motif sequence from the sanctuary for Pth-htbw II: Tfj in Saqqara; Six phases of a fight between two young opponents are shown executing technically perfect grips, swings, and throws in a varied and lively fashion. The two young opponents are even identified by name inscriptions. Ten sculptures of grappling pairs serving as grave goods in relatively simple burials are verified. They constitute a peculiarity of the period from the end of the 6th to the 11th Dynasty (about 2345 BC – 1991 BC).

The “Large Grappling Ground” in the grave of B3qtj III (Baqet), Beni Hasan.

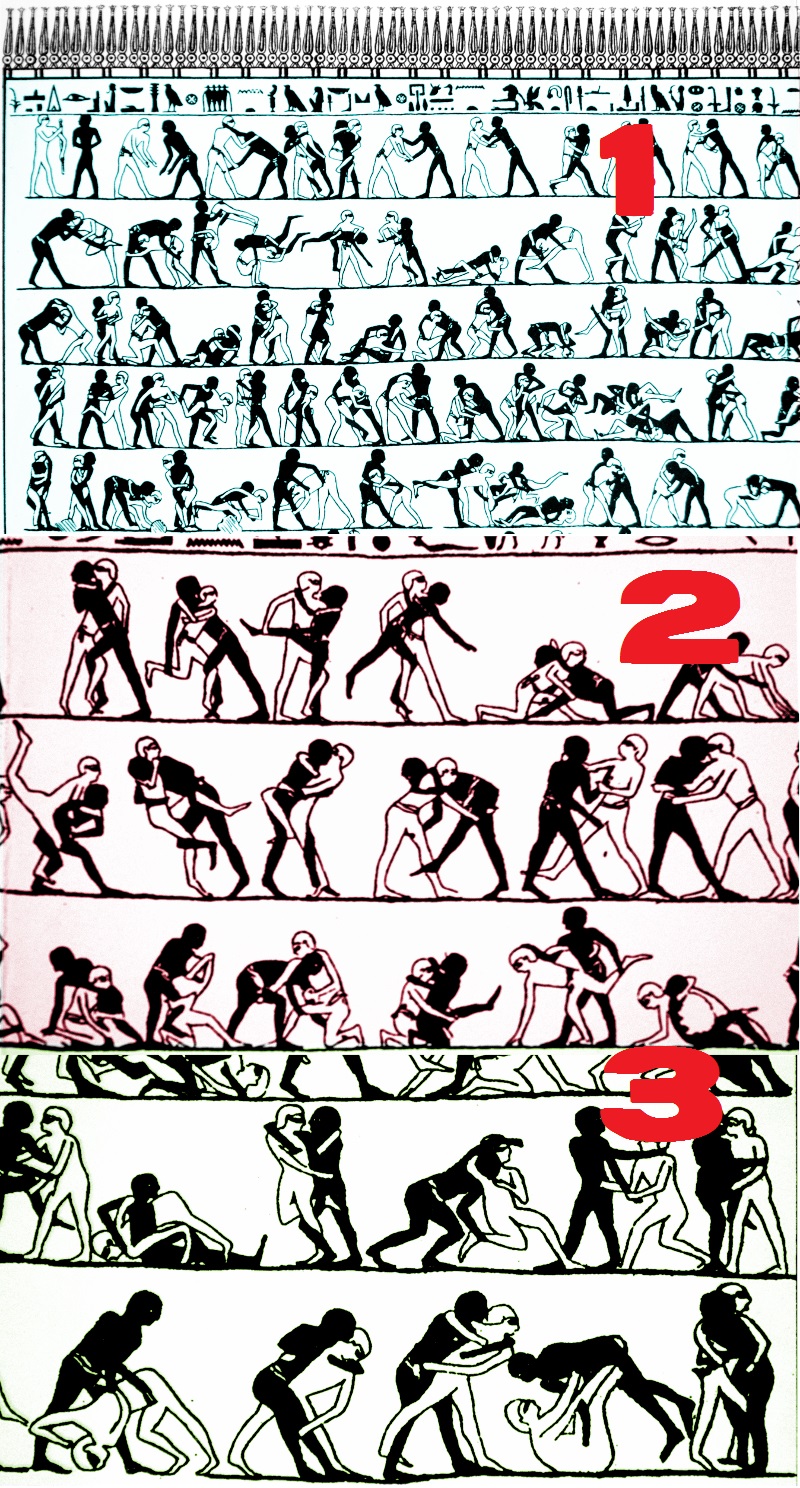

The culmination of relief pictorial rendition of ancient Egyptian grappling is reached with the representations in six nomarchs’ tombs of Beni Hasan, in which partly half of the walls are covered with long sequences showing figures of grappling athletes. These historical materials are unique in the world history of wrestling, in fact in the world history of sport and martial art. Therein the Egyptian decorator implemented the complexity of human movement into the flat pictorial reliefs in a unique way that reflects the high level of Egyptian grappling culture.

The “Middle Grappling Ground” in the grave of Htjj, Beni Hasan

As regards the rules and regulations of the grappling sport, and despite the unique and large fundament of historical source materials, modern research does not go beyond some basic knowledge. The otherwise naked fighters only wore a long belt, which was wrapped around the waist and allowed for additional grips, while grips were otherwise allowed on the whole body. As the ground position is found in only about 2% of the pairs of fighters it remains unclear for the time being whether the freestyle fight was regularly continued on the ground.

The “Small Grappling Ground” in the grave of Jmn-m-h3t, Beni Hasan

The reason for the strong emphasis on the grappling in Beni Hasan was possibly motivated by a military interest: The individual grappling pieces are so closely connected with war scenes that it certainly gives the impression that it were soldiers who are depicted here. More pointers towards rules and regulartions appear in Meir, El-Berscheh, Theben-West and from the Qubbet el-Hawa, which not only clarify new contexts, but also tell of quite important details not found in the large-scale figure sequences of Beni Hasan. Of particular interest here is the figure of a coach or referee standing next to a couple of fighters and who controls the course of events and, where appropriate, seems to intervene.

The temporal focus of these pictorial grappling depictions is the Middle Kingdom (about 2055 BC to 1650 BC). Mostly all the above materials can be dated to the reigns of three rulers which followed one another in immediate succession: the kings Mentuhotep Nebhepetre (11. Dynasty), Amenemhet I., and Sesostris I. (12. Dynasty). This points to a relatively short period of time in which the art of grappling flourished.

The temporal focus of these pictorial grappling depictions is the Middle Kingdom (about 2055 BC to 1650 BC). Mostly all the above materials can be dated to the reigns of three rulers which followed one another in immediate succession: the kings Mentuhotep Nebhepetre (11. Dynasty), Amenemhet I., and Sesostris I. (12. Dynasty). This points to a relatively short period of time in which the art of grappling flourished.

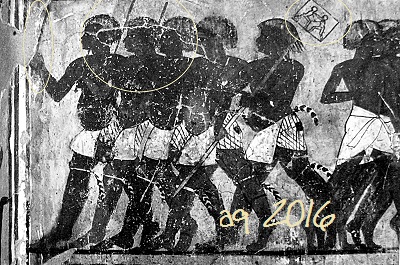

The New Kingdom (about 1550 BC to 1077 BC) entailed some significant changes. On the one hand a very close relationship commenced between depictions of grappling and stick fencing. In all the materials showing a greater scenic context stick fencers are seen alongside the grapplers. This could be interpreted as an indication that both disciplines were carried out by the same actors. On the other hand since this time without any doubt major events of a “show-like” character were carried out, within the framework of which the athletes appeared and whose most prominent spectator was the king himself. Finally, with the Nubians non-Egyptian actors appear on the scene, who possibly introduced entirely new fighting traditions to Egypt. From their physics they seem to be predestined for this discipline. Their descendants, the Nuba in today’s Sudan, apparently preserved their predilection for grappling until the present day and rewards the highest social prestige to the successful sportsmen. The Nubians in ancient Egyptian services can be seen in the famous troupe in the tomb of T3nwnjj (Tjanuni) with their grapplers flag. Their descendants 3500 years later still fight in a similar apparel. For reasons of overawing they add big calabashes to their fighting costumes, which break and cause intense pain when the grappler falls upon them by the action of the opponent.

Finally there are some ostraca from the Ramesside period, i.e. the 19th – 20th dynasty (about 1292 BC to 1070 BC), which illuminate the theme of Nubian wrestlers in a new way by showing Nubian boys in wrestling matches.

II. Stick Fencing

In addition to grappling stick fencing gained greater importance among the various types of ancient Egyptian single combat during the time of the New Kingdom (about 1550 BC. to 1070 BC.). Perhaps it continues to exist in a modern descendants, the nabbût, which is still found today in the Nile valley. This single combat method has evolved into a sporting discipline with a modern set of rules and provides a good example for an autochthonous sport tradition.

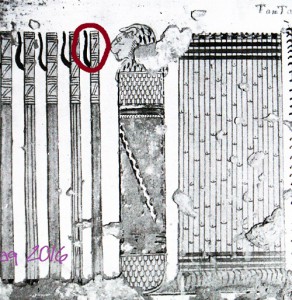

The few but fortunately very carefully executed and detailed illustrations of ancient Egyptian stick fencing show that a fairly extensive equipment was used to conduct the bouts. The most important instrument of the stick fencer was the striking or fencing stick of about am arm length.

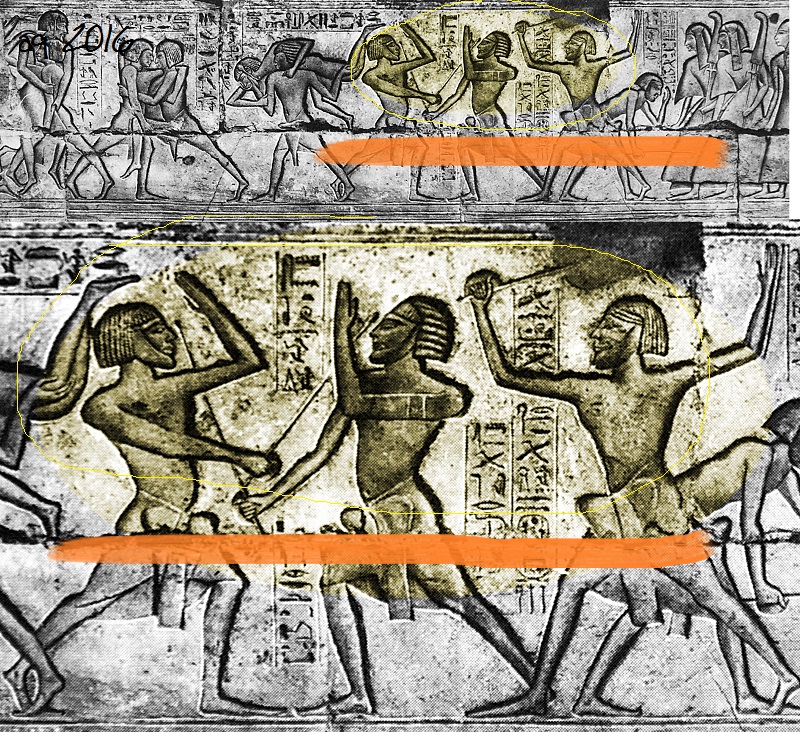

Fencing scenes – left: two fencing soldiers, sketch on an ostracon; right: Stick fencers in front of a chapel to the cult statue of King Tuthmosis III.

The specimen discovered in the grave of Tutankhamen (Theben-West, Biban el-Muluk No. 62) are about 100 cm long and thus confirm the impression of the pictorial testimonies. Formed from a single piece of wood, the weapon is straight and may be reinforced at the top by a metal fitting. The rear end, where the stick was usually held, is equipped with a strong cross-guard or semi-circular shaped attachment that protected the back of the hand and the fingers of the athletes against the blows of the attacker. Important constituents of the fencing equipment are additional protective equipment meant to intercept and mitigate the painful impact of the percussion. The free arm, whose hand did not wield an offensive weapon, could be equipped with a board-like shield that extended either from elbow to fingertips or only from the elbow to the wrist.

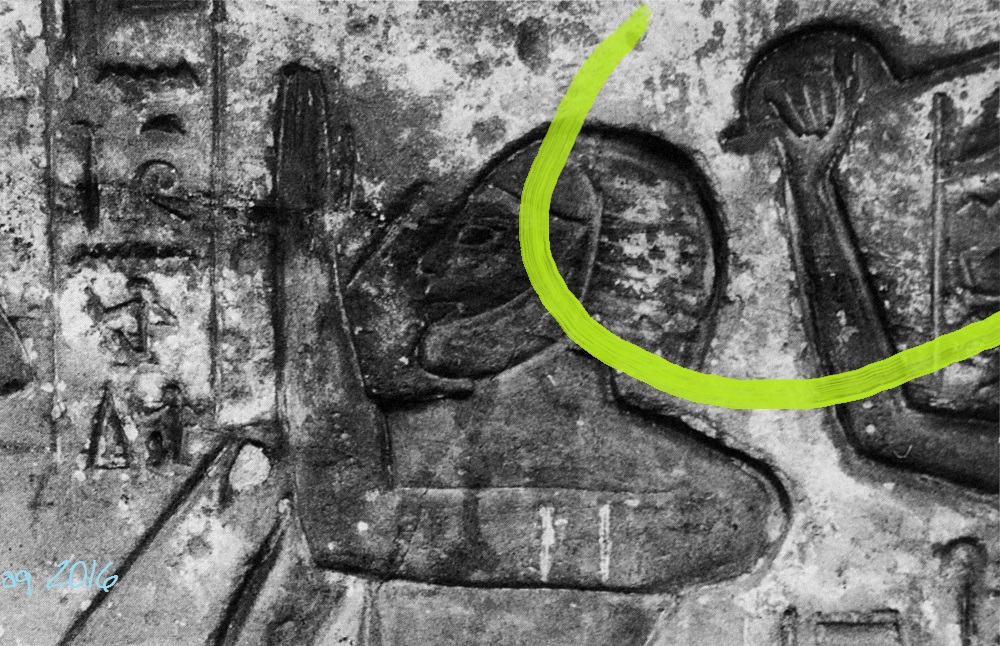

Stick fencer representations under the “Window of Appearance” (or snapshot of life) of Ramses III.

Furthermore, chin and forehead could be protected by broad leather layers, although it is not clear whether the actor put it on in form of a cap, or whether he just covered the respective portions with strips of leather.

Usually the two rivals in the fight carried a fencing stick as an offensive weapon in one hand and employed the other armored forearm with the shield for defence. Obviously, however, there were also other variants. Thus, the armament could consist of two sticks simultaneously used with right and left hand; in this case a protective reinforcement the forearm was omitted. Another variety shows one fighter with a baton in one hand and forearm protection on the other. His counterpart uses two sticks simultaneously and interestingly both forearms of this athlete are also covered by defense shields.

First indirect appearance of stick fencing in the grave of Tjanuni in Theben-West: group of men carrying a banner with the image of two wrestlers. They also hold fencing sticks in their hands.

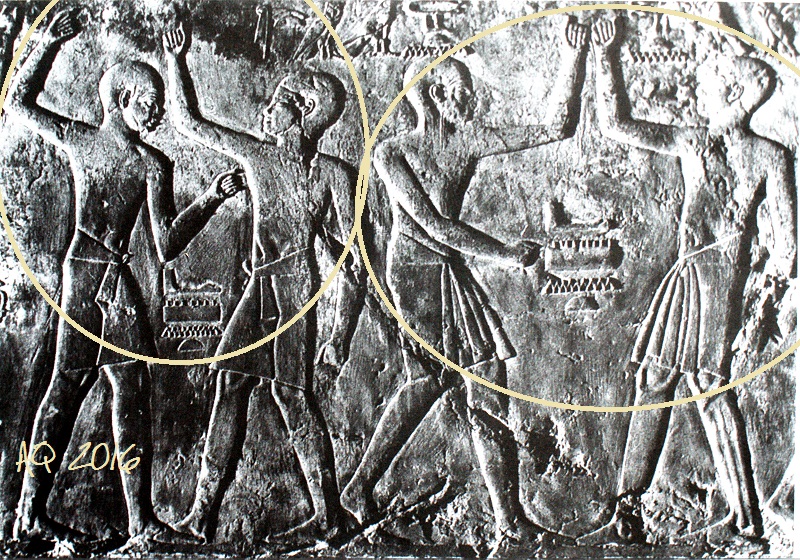

Already in his first indirect appearance in the grave of T3nwnjj (Tjanuni) (Theben-West, No. 74) stick fencing reveals its close relation to grappling, as the depicted group of men not only carry a banner with the image of two wrestlers on it, but also hold fencing sticks in their hands and so draw the attention to the double qualification. Artistically advanced are the depictions of stick fencing in the tomb of Hrjw=f (Kheruef) (Theben-West, No. 192), which appear in connection with the anniversary celebration of Amenhotep III. at the station of erecting the dd-pillar. As weapons they do not use simple batons, but heavy cudgel-like papyrus stalks.

Fencing stick as part of the royal grave goods. Note the guard.

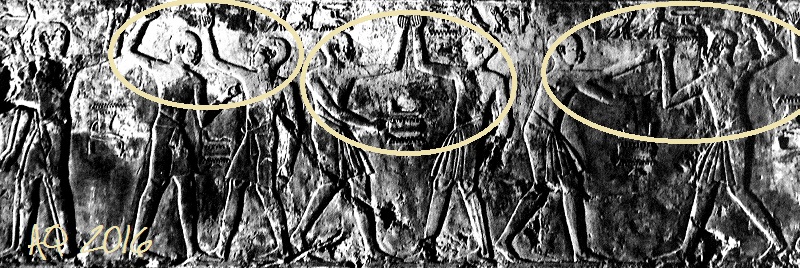

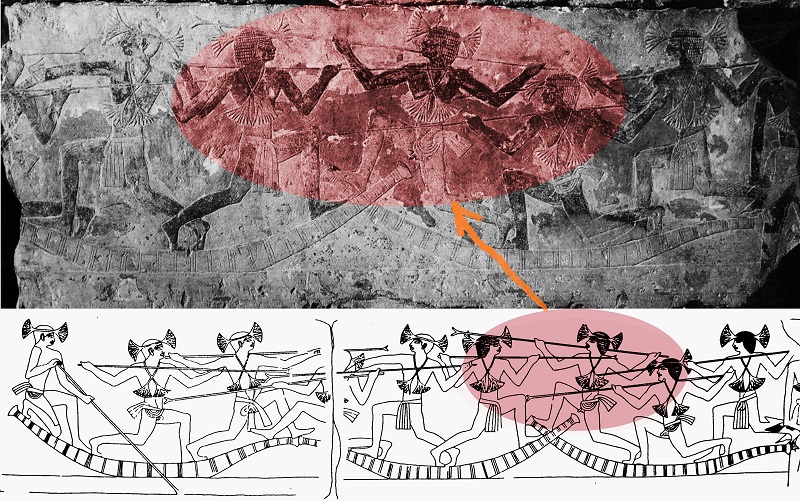

Just as in the case of grappling the appearance of Nubian, i.e. non-Egyptian athletes and the use of papyrus stalks at the celebrations for Amenhotep III. suggest that already in the second half the 18. Dynasty, i.e. at the beginning of the pictorial tradition of stick fencing, several fencing arts were practiced in Egypt, each of which with its own origins and its own characteristics. The clear indication of the complexity of the stick fencing culture in Egyptian antiquity provides a relief block from a destroyed building of the Amarna Period (14th and 13th centuries BC.). In addition to the aforementioned grapplers here wait stick fencers likewise of black African origin, carrying in their hands mighty, almost man-sized sticks, which not only differ considerably from the typical Egyptian fencing equipment, but certainly followed a different set of rules and required different combat strategies from the athlete.

Maginification of the hand guard. Stick fencer representations under the “Window of Appearance” (or snapshot of life) of Ramses III.

III. Pugilism

The third discipline of combat sports, the pugilism, is only rarely found among the Egyptian sources. The oldest and at the same time most beautiful example comes from the tomb of the already mentioned Hrjw=f (Kheruef) in Theben-West, in whose celebratory portrayal a total of six pairs of fighters appear. Despite the frugal expression of movement and the lack of actual hits in the figures one can not help but consider them as pugilists. This perhaps also holds true for the pair of fighters N2 from among the combat sport depictions below the “Window of Appearance” (or “snapshot of life”) of Amenhotep IV. in the tomb of Mrjj-rc II (Meryre) in El-Amarna (No. 2), which occasionally is regarded as pair of grapplers when actually it is much more likely to show the movements of pugilists, which becomes more evident when examining the original.

The pictorial tradition of the New Kingdom (about 1550 BC. to 1070 BC.) clearly demonstrate that all combat arts were not only carried out in an improvised fashion and within a very narrow environment, but above all were integral parts of the official events with a strictly organized chronological sequence and which provided a varied program to the audience. Like this the ceremony held on occasion of tribute deliveries by foreign peoples during the Amarna Period included competitions in the all three related disciplines of grappling, stick fencing, and pugilism. Competitions in stick fencing and pugilism were performed as part of the anniversary celebration of Amenhotep III. In addition, the grappling and stick fights near a statue shrine of the deified pharaoh Thutmose III. deserve special mention. They are displayed in the tomb of Jmn-msw (Amenmose) (Theben-West No. 19). Just as in the case of so many other sources of Egyptian combat sports the fighters appearing in this scene are soldiers – a fact which points to the close relation of the combat sports to the military sphere. Their provocative reciprocal speeches are consistent elements of the ten fighting scenes found in the “international matches” shown below the “Window of Appearance” (or snapshot of life) in the Palace of Ramesses III. in the first courtyard of his death temple in Medinet Habu. Seven pairs in wrestling and three in stick fencing prove their skills in front of a large crowd, among which are many foreigners. One is inclined to view these matches were paired according to the principle of an Egyptian who is victorious against a foreigner, so that the matches shown would have been decided from the outset.

IV. Water Jousting

A total of 48 flat relief pictorial documents about water jousting lead to an entirely different area of life and to the fourth discipline subsumed under combat sports. The by far largest share of materials date from the time the 5th and 6th dynasties (2494 – 2181 BC) – a fact that might suggest that this tradition was carried out mainly during the Old Kingdom and that it was a lost tradition in later eras. The few documents extant from the Middle and the New Kingdom can be considered examples of the continuation of the old pictorial tradition rather than as faithful reproductions of combative events of real life. Notwithstanding it cannot be denied that the ancient custom of water jousting was maintained in a distant echo during the New Kingdom. This is implied in the mythological story The Contendings of Horus and Seth in which the two divine claimants fight in a boat competition for the vacant throne of the “king of gods”.

Strikes, thrusts, and even levers were the main techniques used with the punting poles: The men actively take action against their antagonists in the neighboring rafts or defend themselves against their onslaught, respectively. In these activities, punting poles are employed as weapons but an intention to injure is not visible.

The scenes of water jousting are usually integral parts of longer picture cycles portraying the life and work of people in the spacious papyrus and swamp thickets of Egypt. The focus of these representations are the different productive activities typical for these areas, like the arduous and energy-sapping harvest of papyrus or reed, plucking of lotus flower grounds, the different types of fishing with nets, spears, and fishing poles, bird catching, herds of cattle accompanied by shepherds and others. Papyrus or reed were used to build rafts for the transportation of the various cargoes from the outlying marshes to the settlements and included bundled papyrus stems, lotus flowers, boxes with captured birds, large panniers stuffed with various crops of the wetlands etc. These scenes are generally referred to as “homecoming scenes”.

Transition to grappling.

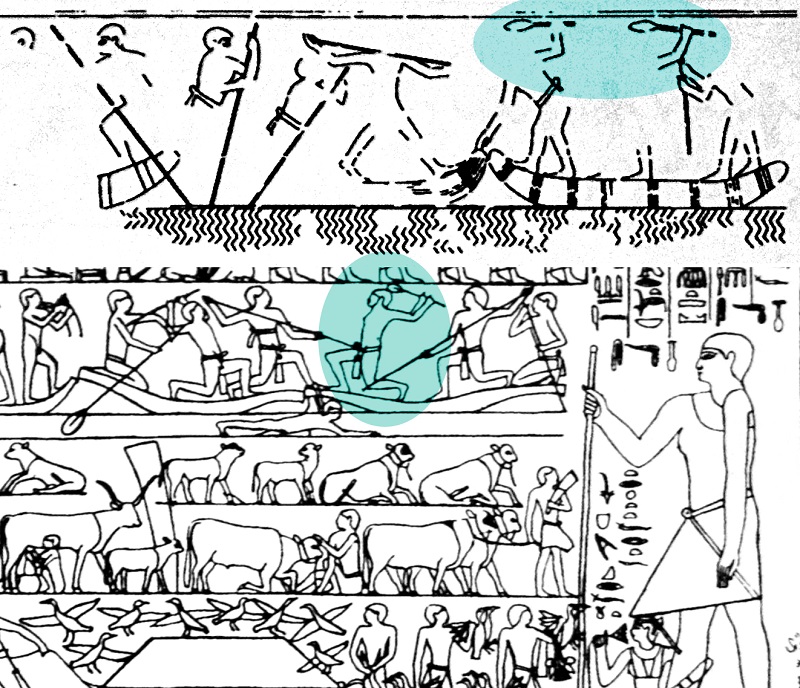

By the beginning of the 4th Dynasty (c. 2613 to 2494 BC) a second type of “homecoming scenes” emerged, dominated by two or three, and in rare cases more rafts, which are loaded with the various products of the marshes and which are propelled through the shallow, marshy waters by several men with long punting poles. Towards the end of the 4th Dynasty a branch of this scenic type emerges, which tells that the men on board the laden rafts not just camly punt them forward, but obviously carry out a sort of battle against each other. There is no evidence indicating that the punting poles are employed as “spears” or as throwing weapons. This suggests the these “battles” show events similar to competitions, or perhaps to sports competitions.

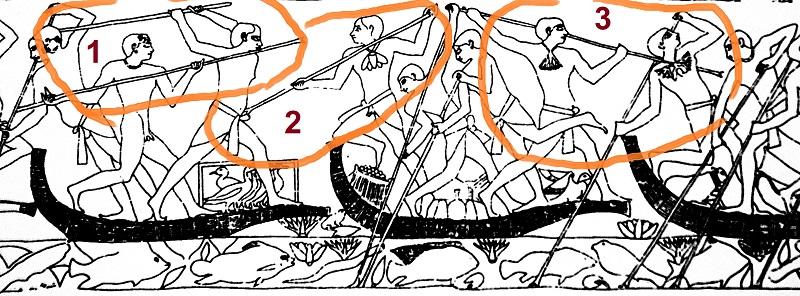

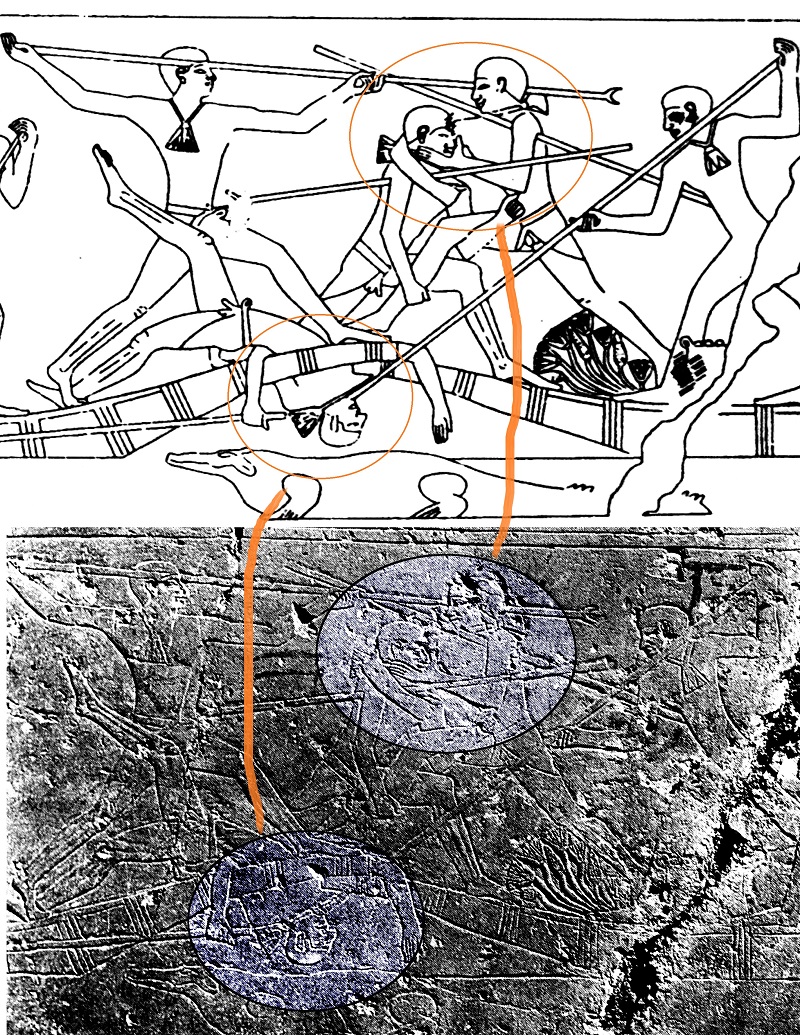

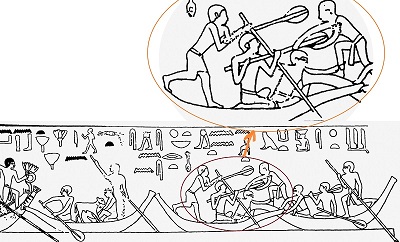

The fighter with the punting pole always seems to advance in a mighty lunge forward. In the middle can be seen the transition to grappling. The single combat is initially performed by using the long punting poles and heavy paddles, but during the further course it turns into a close “in-fight” in which the men continue to fight with their bare hands. The intensity of the actions suggests that altogether great hardness was inherent to these fights. Blunt injuries caused like contusions etc. by blows and strikes are apparently allowed for and taken into account. The grappling follows the stage of the single combat with poles and paddles.

The earliest document of such images that Egyptology has characterized with the label “water jousting” still contains all the elements typical for the “homecoming scenes”. The voluminous raft on the left side of the scene is heavily laden with all those goods that the men have produced in the marshes. In addition, however, in the right part of the scenic composition appear two other rafts, which are completely unloaded and the crew members of which slash at each other not other with their paddles but partly also with their bare hands.

Paddles are also used in the fighting, mainly as impact weapons to strike: Although comparatively seldom, every now and then the punting poles are replaced by paddles. The “paddle wielders” seems to employ the paddles similar to club, swinging it with only one hand raised up to about head level.

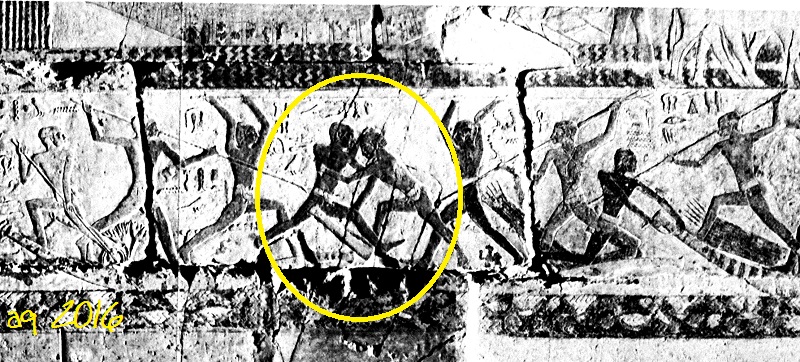

The classic design of this type of scene, which is included in the grave decorations from the middle of the 5th Dynasty (about 2494 to 2345 BC), shows a total of two papyrus rafts and their crew members, who not only maneuver their boats through the shallow wetlands, but who also fight against each other with a great hardness. As weapons the men deploy the long punting poles commonly used for propulsion of the ponderous watercrafts. With their poles the men thrust and strike at their counterparts on the other raft and obviously try to throw one of these opponents into the water. During these confrontations the two rafts occasionally come very close to each other so that the punting poles lose their effectiveness due to their length. In such a case two participants now fight with their bare hands in a grappling match.

Participants now fight with bare hands in a grappling match. Note how two “polers” work together pinning one man into the water: Reports on two fighters who attack their fallen opponents with their punting poles: the one fighter appears to be directed against the neck, the second against the solar plexus of the fallen man.

Besides the thrusting and striking with the poles the grappling as well as the fall of one fighter into the water constitute important stages of the combative event and are processed in individual pictorial motifs and are elements that repeatedly appear in the tradition of this type of scenes. When enough space is provided the decorators also expanded the scene and doubled the number to four rafts with their crews. All the scenes have in common the rich cargoes the men have earned in the marshes and which are now distributed over the deck.

Within the depictions associated with “ancient Egyptian water jousting” there are 1) those men who go at each other with poles or paddles, 2) those who use poles or paddles in single combat, and 3) those who grapple with each other.

As the rafts transport the typical products of the work in the marshes, which were produced during a prolonged stay, the time of these scenes seems to be limited to the returning home. This in turn suggests that the water jousting was not an arbitrarily improvised combat action, but a planned event in which the seasonal workers, who had spent a long time in the marshes, not only celebrated the success of their activities but also the return to their homes.

Use of paddles.

Moreover, there are also scenes with a total of three papyrus rafts in a row with their crew members involved in some way in confrontations. The men of the middle watercraft are apparently exposed to simultaneous attacks both from the right and the left rafts. Undoubtedly, such depictions have determined the view that depictions of water jousting were based on more serious brawls or quarrels that had broken out among the marsh workers. However, and as difficult as it may be, the composition with three papyrus rafts can not be detached from the thematic context they are embedded in. It is therefore concluded that the images showing three rafts lie at the terminal point of a decorative development process during which the ancient artists tailored new compositions of the predefined figures and elements according to the circumstances of a respective tomb. The meaning of the images, however, remained unchanged by this process.

Within the narratives found on ancient Egyptian tomb murals can be seen a specific type of motif known in Egyptology and – as an outcome of it – in sports history under the name of “water jousting” or “ancient Egyptian water jousting”. These are mock battles with punting poles and paddles between the crew members of different watercrafts.

Biblio

Decker, Wolfgang und Herb, Michael: Bildatlas zum Sport im alten Ägypten. Corpus der bildlichen Quellen zu Leibesübungen, Spiel, Jagd, Tanz und verwandten Themen. Teil 1: Text (ISBN 9004098828). Teil 2, Abbildungen (ISBN 9789004098824). Handbuch der Orientalistik. E. J. Brill, Leiden – New York – Köln 1994.

Herb, Michael: Der Wettkampf in den Marschen. Quellenkritische, naturkundliche und sporthistorische Untersuchungen zu einem altägyptischen Szenentyp. Georg Olms Verlag, 2001

Piccione, Peter A.: Sportive Fencing as a Ritual for Destroying the Enemies of Horus. In: Teeter, Emily and John A. Larson (Eds): Gold of Praise: Studies on Ancient Egypt in Honor of Edward F. Wente. Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization 58. The University of Chicago, Oriental Institute, Chicago 1999. Pp. 335 – 349.

© 2016, Andreas Quast. All rights reserved.