hen speaking of Okinawa Kobudō, here and there the term gūsan appears. The gūsan is a specific stick weapon. Not much is known about it and and it can perhaps be called a niche method. In the western understanding it is a stick of medium length, which has been handed down in Okinawa as a specific self-defense method. Since no details are known, it is usually assumed that it is something like the Japanese hanbō or jō, and this is not entirely wrong.

hen speaking of Okinawa Kobudō, here and there the term gūsan appears. The gūsan is a specific stick weapon. Not much is known about it and and it can perhaps be called a niche method. In the western understanding it is a stick of medium length, which has been handed down in Okinawa as a specific self-defense method. Since no details are known, it is usually assumed that it is something like the Japanese hanbō or jō, and this is not entirely wrong.

On the textualisation of foreign terms

Technical terms, for which there are no native Japanese names, are transliterated by using the phonetic system called katakana. This can be seen everywhere, especially in foreign names, technical terms and designations. An example is the Japanese word for bread, pan パン, which is derived from the Spanish lanugage.

Big city neon sign using Katakana.

In Okinawa, terms of foreign origin are and were also given in katakana. In the field of cultural history it is important to understand that many foreign terms were included in the Okinawan language over the course of history, wherein their pronunciation changed. They then became Okinawan words, reproduced in katakana. Thereby, in the case of Chinese word origins, the original characters were often simply neglected and forgotten, and thereby the reference to their original meaning was lost.

The reconstruction of the original characters

In some cases we achieve relatively plausible reconstructions. In others, the question of the correct meaning remains open.

As an example, the Karate Kata Shisōchin can be used: Although several notations in Sino-Japanese kanji exist, that not only reflect the phonetic pronunciation of Shisōchin, but also define a meaning, it is unclear to this day whether they actually reflect the original meaning. As regards the various existing notations of „Shisōchin“ I have been told by a 10th dan Karate Kobudō on Okinawa, that all existing attempts to reconstruct the phonetic pronunciation of Shisōchin by means of Sino-Japanese kanji are wrong. Fact is that already the first written mention of Shisōchin in 1867 was written in katakana.

Or a more familiar example: Everyone has heard of the kata called Heian. This is interpreted as peace, silence or harmony, or as a reference to the imperial court of the Heian period (794–1185). However, when Funakoshi published his first books, the name was given as Pinan, using the writing style of Katakana for foreign words. On Okinawan these kata were always called Pinan. Its origin in turn is the Chinese term Ping’an 平安, ie: safe and sound, healthy and happy, without accident, without incident.

The situation is similar with the Okinawan term gūsan.

Gūsan as an Okinawan compound word

Gūsan is a term used in the Okinawan language. So one can try to interpret this term based on this Okinawan language alone. As the compound word, gūsan can thus be interpreted as follows.

The syllable gū can be translated, for example, as “friends” or “allies”. For the syllable san there are at least six different possibilities of interpretion. One can interpret the meaning as “leaving an offering to the gods”. But the syllable san can also designate a stick, albeit one that is specifically designed for closing a door.

From the different combinations it is possible to make up some sort of meaning.

From the variety of homonymous syllables numerous possible combinations result.

Gūsan in the lexical meaning as a single word

Unlike the above try, gūsan can also be interpreted as a single word in its lexical meaning. In this case, it simply means stick or crutch, using a comparative statement of the Japanese word tsue 杖.

Further lexical meanings suggest a a use primarily in cultural connection with the religious beliefs of Okinawa. An example is the dashichā-gūsan. This is a stick manufactured from the wood of the dashichā (lat. Randia canthioides Rubiaceae): When announcing oracles the holy women of Okinawa hold such dashichā-gūsan in their hands. It is also referred to as “exorcism stick”.

Two Gusan-uji in an Okinawan family altar.

Another example is the gūsan-ūji. These are sticks made from sugar cane, which serve as an offering. At the Obon festival according to the old calendar these sticks are placed as an offering on both sides of the Buddhist house altar. This has something to do with the belief in the return of the spirits of deceased ancestors, their salvation, and finally their return to the shadowy worlds.

Gūsan in combative sense

I am not aware of any lexical definition of the term gūsan as a stick used for fencing. In the case of refunctioning for self-defense, however, the gūsan can be interpreted as a fencing stick. In this case, a specific meaning would be attributed to the gūsan. Similar to the above given lexical meaning, the gūsan would then be comparable to the Japanese jōjutsu, the shikomi-tsue and other short to medium length fencing poles of different characteristics. That is, the gūsan may have been converted from everyday objects to a weapon-device. And like this it is found in some Okinawan schools used as a weapon, for example in the

- Ryū’ei-ryū of Nakaima

- Shōrin-ryū Shūbukan of Uema

- Motobu Udundī

- Matayoshi Kōdōkan Dōjō

and probably others.

Shikomi-tsue

Nakamoto (2007) also counted the gūsan among the fight-ish stick methods:

In the rural villages at festivals such as the Eisā- or the Bon-dance stick dances are performed as a pastime, which are called Bō-odori. In a colorful environment quite exaggerated techniques and movements are presented, wherein the bō is often conducted far away from the body. From the standpoint of the martial art we therefore have to say that this stick dance is full of openings. In combative Bōjutsu, on the other hand, as the Mēkata-Bō and other combative stick methods, it is referred to as […] Gūsan, […] and the like.

Gūsan derived from Chinese

An etymological reconstruction of the term gūsan revealed that the term resulted from linguistic adoption and transformation of the Chinese term guaizhang. Guaizhang literally means crutch or cane and particularly refers to a walking stick for older people. The fighting techniques the system of this walking stick is referred to as guaizhang-shu. There are only a few representatives of this kind in existence in the northern and southern styles of China.

As material for this weapon a particular wood is used, namely that of an old wisteria tree (lat. Wisteria floribunda). In addition, rattan and cane be used.

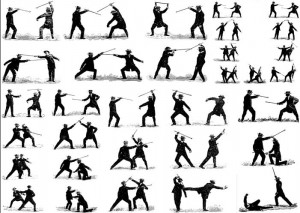

Bartitsu as an example of a fencing method with a walking stick

Nakaima Kenri of the Ryūei-ryū learned the damo-guai – the staff of Bodhidharma – in the area of Fujian before returning to Okinawa. According to this perspective, the guaizhang or its short form guai in Okinawa were corrupted to gūsan, in the specific meaning of a fencing stick. Such fencing methods with walking sticks exist worldwide, and moreover, they are historical. Already the ancient Egyptians used similar stick and lengths and in the not too distant past Bartitsu is found as an example of a fencing method using a walking stick. There are numerous others.

Interestingly, although the Chinese term guaizhang is a composite word, too, we come to completely different conclusion than in the above section Gūsan as an Okinawan compound word. This is the crux of reconstruction.

Resume

When the term gūsan first appeared in Okinawa remains just as unclear as its original meaning. Whether as arbitrary term for several sticks of everyday life, whether as religious offerings, as exorcism sticks of priestesses, or as a fencing stick; Whether as an indigenous word or as a derivative from the Chinese guaizhang: so far this question can not be answered.

In the Jigen-ryū suitable branches were cut off certain tree species.

In combative sense, however, gūsan designates nothing but a stick of approximately the length of a walking stick used for fencing. Accordingly, an infinite number of applications can be derived ad hoc from jōjutsu, hanbōjutsu and others.

Presumably, the sticks for the gūsan were selected from nature and manufactured without expensive manufacturing methods. When Uema Jōki (1920-2011), the late founder of the Shōrin-ryū Shubukan Uema Dōjō on Okinawa, demonstrated a kata using the gūsan, it were all naturally grown and minimally reworked sticks. The Shōrin-ryū Shubukan Uema Dōjō today is headed by Jōkis son Uema Yasuhiro, who also took part in the above demonstration.

Uema Jōki (1920-2011), the late founder of Shōrin-ryū Shūbukan Uema Dōjō on Okinawa, with a kata using the gūsan. The gūsan used here are naturally grown sticks.

Similar to the Jigen-ryū you can use the branches of suitable woods. For the Gūsan the already mentioned and traditionally used wisteria tree is recommendable, as well as rattan or cane. Hazelnut tree and many other woods are just as suitable.

Looking at the enbusen and the techniques used by Uema, it can be seen that they are basically the same techniques as in bōjutsu. In addition, despite its shortness the gūsan is handled with both hands all the time, without a change to one-handed operation taking place. In addition to the techniques themselves, this is the most striking parallel to bōjutsu.

This doesn’t mean that this was always and exclusively the case. Quite on the contrary. I tend to believe that this kata is a modern creation with a gūsan, designed by using earlier traditions.

© 2015 – 2023, Andreas Quast. All rights reserved.