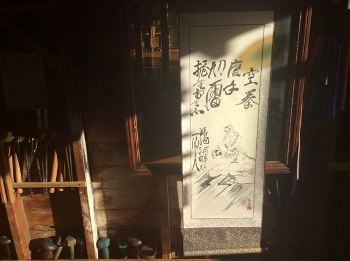

his article describes the life and impact of Arakaki Ankichi (1899-1929). Ultimately it aims at determining the meaning of a hanging scroll bearing a poem and a depiction he created in 1928. It took me nearly seven years – more off than on though – to finally come to a conclusion as regards the meaning of the scroll. And it’s unique.

his article describes the life and impact of Arakaki Ankichi (1899-1929). Ultimately it aims at determining the meaning of a hanging scroll bearing a poem and a depiction he created in 1928. It took me nearly seven years – more off than on though – to finally come to a conclusion as regards the meaning of the scroll. And it’s unique.

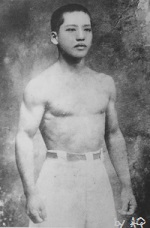

Ankichi. Original photograph documented by Andreas Quast at the Kodokan dojo in Naha Kumoji.

I dedicate the article to two persons: First, Nagamine Takayoshi, from which I had the honor, pleasure, and duty to personally be taught karate and through whose generosity I was able to intitially admire and document Arakaki Ankichi’s original picture scroll. The second person I dedicate this article to is Lara Wendy Preston Chamberlain, who caused me the greatest and long lasting delight when almost out of the blue she presented me with a unique re-production of Arakaki Ankichi’s hanging scroll. Her re-production is so real and true to the original that I am still perplexed this was even possible. Simply Amazing!

Note: In this article I use the first names of the persons as much as possible. It is meant to spare space but also to make the tradition of Okinawa Karate more personal and less formal. I hope this is ok.

Arakaki Ankichi (1899-1929)

nkichi was born in November in the year of the boar, 1899, in Shuri Akata, Naha City. He was the eldest son of eleven siblings of a wealthy family of liquor merchants who later relocated to Shuri Torihori. Their store was named ufugū ufuyā-gwā.

nkichi was born in November in the year of the boar, 1899, in Shuri Akata, Naha City. He was the eldest son of eleven siblings of a wealthy family of liquor merchants who later relocated to Shuri Torihori. Their store was named ufugū ufuyā-gwā.

Ankichi was blessed with a splendid physique and ingenious martial talent. In his elementary school time he studied karate under Shiroma Shinpan (1890-1954) and during junior high school time under Hanashiro Chōmo (1869-1945). In elementary school he was a quiet but clever boy. In junior high school, however, he began to neglect his studies and to focus more on sports, so that he dropped out of school. Yet, afterwards he studied in earnest with Chibana Chōshin (1885-1969), who was later awarded the Order of the Sacred Treasure, 4th Class, by the Emperor of Japan.

Before long Ankichi was known under the martial nickname “ufuyā-gwā no Ankichi” or “Ankichi from the Liquor Store”.

At the age of 19 spectators were amazed when he won against a giant opponent in an Okinawa sumō tournament. This is said to have been due to his flexible and tough legs. His competence was rated parallel to that of the grand champions (yokozuna) of Okinawa sumō, like Sakumoto Nabe and Yabu Kentsū (1866-1937).

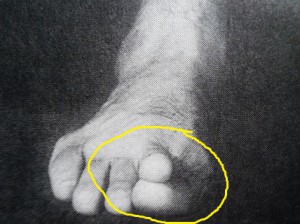

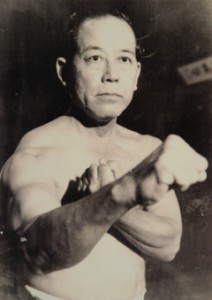

He used to strap iron clogs to his hands and walk up and down the Yamagawa Hill in Kadena; on his hands. In order to train his legs, he practiced jūdō, sumō, swimming, climbing trees in the mountains, and walking on his toes. Throughout the day he continued a series of training practice like double and triple kicks and high jump kicks. In this way, and accompanied by an unrivaled speed and destructive power, he created the unique technique called “ashisaki-geri” or “toe-tip kick”. The following story tells of its power:

Ankichi’s unique forming of the toe-tip for “ashisaki-geri”.

When Ankichi was around 20-years old he happened to be at a brothel in the entertainment district of Tsuji in Naha. In the corridor on the second floor he bumped into a huge man who entangled him to a quarrel. The dispute being inevitable, in the moment he was grabbed by the arm he responded with a tremendous ashisaki-geri (toe-tip kick) into his opponent’s flank and the man sank down on the spot. About six months later an obituary of the man appeared in the newspaper, describing him as a giant sumō fighter who had died from a pulmonary hemorrhage. The article also said that as the underlying cause of death was suspected a kick the man had obtained six months earlier from a karate man.

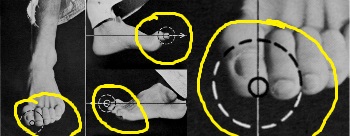

See below a explanation posted on Arakaki’s legendary toe kick by Rh Gutierrez.

In contrast: Sokusen-geri of Uechi-ryu (Uechi 1977). Also called Maeashi-geri. Found in Seisan, for example.

Ankichi‘s younger brother Ansuke once challenged him at home during naughty nonsense. After he exaggerated his provocations, Ankichi kicked his right thigh and Ansuke later had to undergo surgery because of suppuration. When Matsubayashi-ryū founder Nagamine Shōshin together with Higa Yuchoku visited Ansuke and inquired about the incident, they were directly shown the scar by Ansuke.

Fujii Kōtsuchi, Imperial Guard commander during Ankichi’s military service.

Another fascinating story about Ankichi was told to Nagamine Shōshin by Ōyama Chōjo, the former mayor of Koza City, in April of 1968. Around 1920 Ankichi passed his physical examination for the military draft. Due to his excellent physical condition he was chosen to serve in the 3rd Imperial Guard Infantry Brigade Regiment stationed in Tōkyō (Konoe hohei dai san rentai). Ōyama also joined the same regiment. As part of the drill, a river crossing exercise was held by the regiment at Tonegawa river, one of the most dangerous torrents in Japan. A rope had to be taken to a small boat about two kilometers upriver and after securing the boat; the soldiers had to return the 2 km downstream again. Among the few who managed to succeed, Ankichi was the first to return to the shore. He received the high praise of the Imperial Guard commander Fujii Kōtsuchi (1864-1927), intended to raise the morale of other Okinawan soldiers.

Taira Yoshitaka, ashisaki-geri from Tomari no Chinto.

Sometime after his honorable discharge in 1921, in order to see the branch office of his family‘s liquor store, he moved to Kadena. Coincidentally, Kyan Chōtoku lived by the nearby Hija Bridge in Yomitan village. Ankichi, at the age of 25, became the student of 55-year-old Kyan. Master Kyan taught diligently and Ankichi put everything he had into learning karate under his task master. Ankichi, overflowing of youthful power, trained with the minutest care under his mature teacher.

While deeply devoting himself to karate, he realized the value of karate as an art form, which led him to take pride in local arts and culture. At that time, the reputation of the local culture was decreased, and this was not limited to karate, but other entertainment arts, too. People looked down on their local culture, terming musicians as uta-gwā narayun or person studying unimportant music, calligraphers as jī-gwā narayun or person studying unimportant writing, and karate men as tī-gwā narayun or persons wasting their time with karate.

Hating this tendency, Ankichi understood that it was necessary to aim for more than just the physical mastery of karate. So he deeply studied both entertainment arts and karate and viewed it all as a form of culture. Ankichi studied these arts in earnest, not only karate, but also in a wide range of other sports, Ryūkyū music and dance, poems (ryūka), and calligraphy. In particular, he had deep knowledge of poems and created his own, enjoying to show off 100 collected verses of old poems. Rather than being a fully committed pigheaded fellow of martial arts he also excelled in literature and was a unique warrior of tasteful understanding.

Ankichi, Choktoku, and Choki as portrayed by Andreas Quast at the Matsubayashi-ryu Kodokan dojo in Naha Kumoji.

Ankichi thought the real characteristic of martial art was speed. Motobu Chōki, who studied both under Matsumura Sōkon and Matsumora Kōsaku, also emphasized this philosophy. Ankichi’s martial arts philosophy of speed is not a speed to capture a stationary opponent, but a speed of techniques and movements to capture a moving target. Seemingly this perspective was not the ordinary understanding of karate at the time.

During the recession after the WW I, his family liquor business started to stagnate, so he was forced to crisscross in its rehabilitation, yet finally met the hardship of bankruptcy. His life turned around to one of daily poverty and he started to suffer from stomach disorder. On December 28, 1929 he died a premature death. He was only 30 years old.

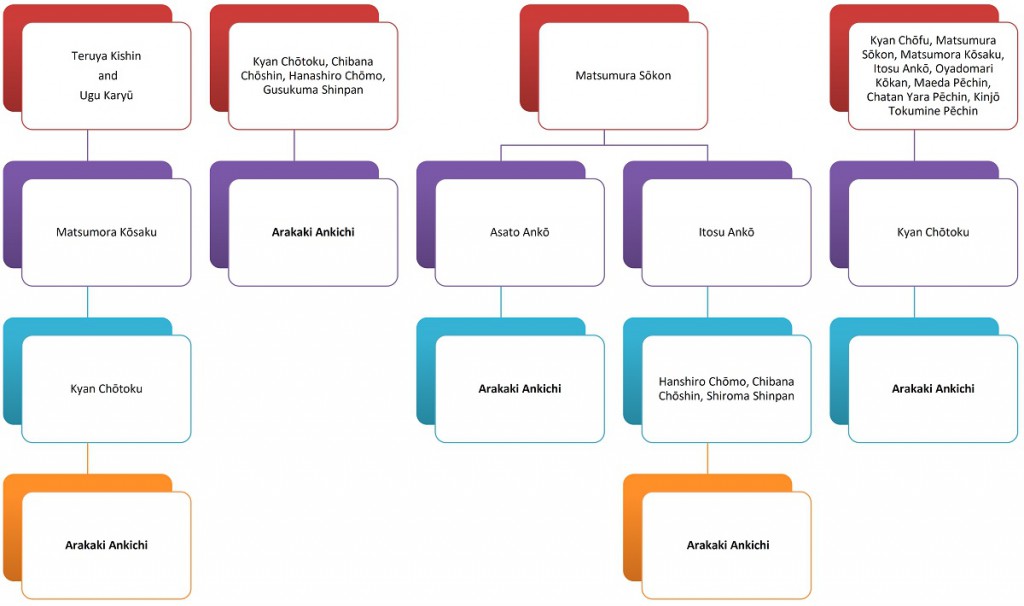

Few person united and excelled an entire generation of Okinawan martial artists in the way Ankichi did. According to Watatani (1978), Ankichi was an expert in karate so much that his tradition was referred to as Arakaki-ryū. The most important personal relations leading to Ankichi can be summarized as follows (from various entries in Watatani 1978).

Episode

Among Chōtoku’s most visible disciples were Aragaki Ankichi (Arakaki-ryū), Nagamine Shōshin (Matsubayashi-ryū), Shimabukuro Tatsuo (Isshin-ryū), Nakazato Jōen (Shōrinji-ryū), and Shimabukuro Zenryō (Shōrin-ryu Seibukan).

Chitose Tsuyoshi (1898-1984), who was born under the name of Chinen, was also a student of Chōtoku. Tsuyoshi remarked that Ankichi was Chōtoku’s best disciple and that he was nicknamed “tsumasaki-geri no Ankichi” (Ankichi with the toe-tip-kick). Tsuyoshi came to know about Ankichi when he heard rumors made the rounds about a very strong guy at Chōtoku’s place. This was Ankichi. Chitose met him by chance at an amusement center:

Chitose Tsuyoshi at Chōtoku’s left side.

“Are you Ankichi?” asked Tsuyoshi. “I know you!”, said Ankichi, “You are little Chinen (Chinin-gwā).”After self-introduction among karate men, it was implicit they would both go for a match. At the time matches were called kakedameshi, considered real fight as compared to yakusoku or prearranged combinations. A cemetery was chosen as the location, and without public. The fight began in the middle of the night. Arakaki was strong as had been told in the rumors. The violent struggle continued, but there was no life or death decision: In the end both fell down tired and exhausted. And when they noticed, it was becoming dawn. In this way Ankichi and Chitose became adopted brothers.

Legacy

agamine Shōshin (1907-1997) began his training in karate at age seventeen, around 1924. In 1925 he entered the school of Shimabuku Tarō in Shuri and in 1927, aged 20, Nagamine and Shimabuku both began to study under Ankichi, who was the top student of Kyan Chōtoku at the time. Ankichi was then twenty-eight years old. Shōshin recalled:

agamine Shōshin (1907-1997) began his training in karate at age seventeen, around 1924. In 1925 he entered the school of Shimabuku Tarō in Shuri and in 1927, aged 20, Nagamine and Shimabuku both began to study under Ankichi, who was the top student of Kyan Chōtoku at the time. Ankichi was then twenty-eight years old. Shōshin recalled:

“Under the guidance of Ankichi, I began to appreciate the spirit and beauty of karate–dō. His modern approach to teaching karate with scientific explanations, the quoting of historical facts, and stories of martial arts in general, fascinated me right away.”

Shōshin. Original photograph documented by Andreas Quast at the Kodokan dojo in Naha Kumoji.

Shōshin trained with Ankichi for one year, until after his graduation from Naha City Commercial School he enlisted in the 47th IJA Infantry Regiment in Ōita in north-eastern Kyūshū for 18 months. In 1929 Shōshin, as can be read in one of his books, returned to the study with Ankichi. It was in December that year that Ankichi passed away in the prime of his life.

From December 1931 to April 1936 Shōshin was assigned to the Kadena police station as a prefectural law enforcement officer. During that time he studied directly under Kyan Chōtoku. He recalled that Chōtoku in his later years taught the village youth in karate and also gave lessons at the Kadena police station and at other places. You may bet that Shōshin visited all these places as often as possible. What we do know exactly according to his own words is that he deeply studied Chōtoku’s favorite kata Passai, Chintō, and Kūsankū. In fact, Shōshin had learned these Kata already earlier from Chōtoku’s top student Ankichi as well as by Shimabuku Tarō. This was karate network learning. According to the dates given, and although slight variations might be possible, Shōshin learned these kata for more than ten years. It is probably from this experience that Shōshin said that it takes at least ten years to master Kūsankū.

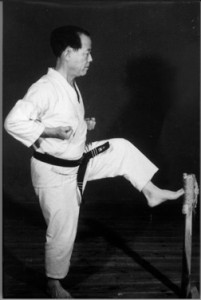

Nagamine Shoshin

Chōtoku often talked to Ankichi about Chatan Yara and his Kūsankū kata. This we know because Shōshin was told about this directly by Ankichi and preserved it in his writings. According to it, the Kūsankū tradition was the principal vehicle through which Yara transmitted the secret applications of karate to Chōtoku. Chōtoku in turn taught it to Ankichi, who taught it to Tarō. Nagamine in turn learned it from each Chōtoku, Ankichi, and Tarō.

Chintō as well as Passai are known to have been favorite kata of both Kyan and his top student Ankichi. The original creator of both of these kata is unknown but they were popular practice handed down in and around the district of Tomari and remain principal kata of koryū or old style karate.

Today these kata are known as Tomari no Passai, Tomari no Chintō, and Chatan Yara Kūsankū. They are quite specific in the Matsubayashi-ryū. As Shōshin explained,

“Although these kata are practiced by many different schools, the way I teach them are exactly the way that Master Kyan, Arakaki Ankichi, and Shimabuku Tarō handed them down.”

Nagamine Shoshin, ashisaki-geri.

When in May 1942 Nagamine opened his first dōjō in Naha’s Sōgenji district, it was the sole private karate school in Naha at the time. Kyan Chōtoku, his personal teacher, came all the way from Yomitan village, together with his assistant Arakaki Ansei – the brother of Ankichi. Chōtoku demonstrated his favorite kata Passai and Chintō as well as bōjutsu in the presence of guests of honor like rear admiral Kanna Kenwa, the publisher of the Ryūkyū Shinpō newspaper Matayoshi Kenwa, the dentist Hidehiko Tomoyose and others. The superb performance by 73-year-old Chōtoku was a demonstration of the very essence of karate that left the audience speechless. Unfortunately, this amazing, memorable performance was one of his last. On September 20, 1945 at the age of seventy-six, Chōtoku passed away in the northern part of Okinawa.

Note: For a large number of eye-witness accounts and original field research gathered by Nagamine Shōshin on many of the Okinawan masters of old, see: Nagamine Shoshin (auth.), Patrick McCarthy (transl.): Tales of Okinawa’s Great Masters.

Shōshin remembered how much he was impressed with Ankichi’s understanding of the Okinawan heritage. This was at a time when most Okinawans underestimated the values of their own culture. For example, Ankichi instructed his disciples that karate and the Ryūkyū dances, considered from their dynamic and movements, had much in common. However, at the same time he stressed that karate developed from the human instinct of self-preservation, while dances developed from the desire of humans to express their feelings. Ankichi said that when studying the dances, a karate man would understand the differences and similarities between the two.

It is from the above personality traits that Nagamine noted:

“Ankichi was a true Renaissance man. Under his influence, I began to study dance and poetry.”

Monkey scene from “The Fateful Encounter of the Flower Seller” (Hanauri no En)

In 1920, the Shuri Fire Fund Association sponsored a classical art and dance performance at Shuri castle’s Northern Palace (kita no udun). As part of the program a classical dance (kumi-odori) called “The Fateful Encounter of the Flower Seller” (Hanauri no En) was performed. This dance premiered in 1808 during the festivities of enthronement of King Shō Kō. Ankichi performed the role of the monkey in this play. With his incredible strength and skills, Ankichi mimicked a monkey perfectly, jumping up onto the big column of the stage and then climbing it upside down. He even picked a lit cigarette out from the mouth of a man in the audience with his toes and puffed on it. Everyone was astonished so much by his striking performance that it became the favorite of the era.

Overview of “The Fateful Encounter of the Flower Seller” (Hanauri no En)

Morikawa no Shī was a lower noble of Shuri. Since he had suffered a misfortune he was no longer satisfied with life. He left his wife Ototaru and his young son Tsurumatsu behind and moved to Yanbaru in the north looking for work. His wife Ototaru, on the other hand, apprenticed as a nanny in a wealthy family of Shuri and lived without incident in peace.

12 years passed by. One day, Ototaru with grown Tsurumatsu heard that Morikawa had been seen and they set out on a journey looking for him.

At Tsuha village they met a monkey trainer. Resting from the fatigue of the journey they watched the monkey perform tricks with the Naginata and others. Later they asked an old person collecting firewood on the whereabouts of Morikawa. The person answered that Morikawa had lived in Tsuha village until last year, but hasn’t been seen recently. He said that people often travel to violent Taminato village and that he might be there. So Ototaru and Tsurumatsu set out to go there.

When they reached Taminato village, they met a flower seller selling plum blossoms. When Ototaru told the person that they are looking for her husband and father, she noticed the man was her husband Morikawa. And when Morikawa extended a plum flower to her, he too realized that they were his wife and son. But ashamed of his poverty he fled into his hut.

However, the joy of reunion of the family by persuasion of Ototaru and Tsurumatsu was stronger, and they returned to live in Shuri again as a family.

Watch and listen to the scene where Ototaru and Tsurumatsu meet the monkey trainer:

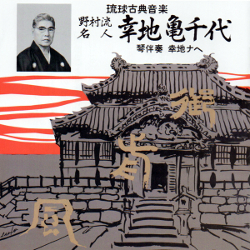

Another eye-witness account was imparted to Shōshin by a late master of Nomura-ryū named Kōchi Kamechiyo (1903-1969), who was also a respected friend of Ankichi and – like Chōtoku – one of the celebrated persons of Kadena town to this day. Around 1922, the Nomura-ryū held a ceremony in front of the grave site of its fonder in Chatan town. During the program the chairman asked if there was anyone who might like to recite an impromptu poem. The only person volunteering was Ankichi, and his peom was very well received. Then Ankichi played and sung the Sanyama-bushi or Scattered mountain tune, for which he received unprecedented applause by all present experts.

Musician Kōchi Kamechiyo (1903-1969), friend of Ankichi.

Ankichi’s Hanging Scroll of a Thunder God

![]()

Shōshin at the tomb of the Teruya family, where Teruya Kishin, forefather of Tomari-te, taught his disciple Matsumora Kōsaku. Original photograph documented by Andreas Quast at the Kodokan dojo in Naha Kumoji.

n 1928, at the request of Dr. Iha Magobei who owned a hospital in Chatan’s Yara village, Ankichi painted a hanging scroll depicting a god of thunder and composed a poem for it while at a party near Murochi. This hanging scroll is a unique specimen of Ryūkyūan martial arts. Arakaki Angi, the brother of Ankichi, presented the painting to Shōshin in January 1984 as a memory of his venerated teacher. It remained in family possession of his son Nagamine Takayoshi. I first saw it displayed at the Matsubayashi-ryu Kōdōkan Dōjō of my late sensei Takayoshi in 2008.

The picture scroll bears a verse on top: Kuken karate hatsukaminari mo nigiri o osafu, to be read from top to bottom and from right to left. It is difficult to interpret, but it is something like:

“The bare hands of karate, seizing the first bolt of lightning.”

Yes, something like that. And now it is getting really interesting. Because during my assessment and evaluation I came to the following conclusion, shedding some light on this alcove-forgotten figure.

Excerpt from the original Ankichi Scroll. Photo: Andreas Quast.

Among the poem is the depiction of a god of thunder (raijin) with two short horns, governing lightning, thunder, and storms. One might suppose an allusion to the young horned dragon found in Ryūkyū myths. On a cloud scattering lightning he rides along through the sky. In his right hand is a drum, which bears three right-rotating commas. With his left hand he wields a drumstick and with his drumbeats unleashes thunder and lightning. His otherwise naked body is covered with a loincloth made of tiger skin. Around his neck he wears a type of scarf, which in fact is the bag of winds of the wind god (fūjin): our figure is a combination of two old Shintō deities, the God of Thunder (raijin) and the God of Wind (fūjin)!

On the left side the picture scroll is signed:

“An immortal mountain wizard from the shores of the pond of time.”

Way cool!

Lara’s Ankichi Scroll. Finished early March 2015. It is not only a 100% perfect artistically implemented reproduction, but also carries the very soul of the original.

As regards gods of thunder and winds mythology, there are many legends across all cultures. Buddha commissioned the gods of thunder with the protection of the cosmic law and order, or dharma. In Japanese shintō mythology, gods of thunder were created by the divine pair Izanami and Izanagi after they created Japan. An example is Takemikazuchi, often revered as a god of thunder and considered the deity of jūdōka and kēndōka, as well as a protective deity of war. In the end, the three right-turning commas are also a symbol for the Hachiman Daibosatsu. For those who wonder: the royal symbol of the Ryūkyū kingdom always had three left-turning (clockwise) commas, as I described here and also here.

In this way, Arakaki’s magnificent example of the artistic culture of the Ryūkyūs compares karate with the fearsome force of nature and merges mythology with poetry and music. At least if you ask me, it carries a message:

Just like the god of thunder and wind in all cultures controls the enormous power of thunder, lightning, and storms, a master controls the enormous power karate. Just like thunder, lightning, and storms are terrifying and destructive and thus need to be controlled by the gods, so does karate need to be controlled by man and women.

Alhough frightening in their power and warlike in their implications, the thunder and wind gods originally were and still are protective deities. Again, the same relationship is valid for karate men and women.

In this way, and independent from its literal translation and screaming linguists, the ultimate meaning of this picture scroll becomes a piece of art bearing witness of the deep humanity and artistic and philosophical ideals of the person Arakaki Ankichi.

Watch and listen to Sanyama-bushi or Scattered mountain tune performed by the Nomura-ryū:

© 2015 – 2020, Andreas Quast. All rights reserved.