Over the last 120 years, the technical syllabi and contents of “karate” have constantly been reviewed and aligned to various aims and ideas. Within this process, not only were new methods created, but also were various existing martial arts methods and techniques integrated into “karate.” Such methods and techniques are often indiscriminately and retrospectively treated as if they were all proven contents of “historical karate,” however, this is not necessarily the case. Rather, all sorts of other martial arts methods were continuously looked into by various people at varying times. Such methods and techniques came to be cumulatively placed within the infinite variety of existing “karate” syllabi, and henceforth been practiced in reference to “karate,” its kata, and its historical narratives.

Based on the assumption that all conceivable methods must be historical techniques of “karate,” the technical corpus of practical applications of “karate” grew exponentially to its current magnitude. It should be noted that the extensive current corpus of practical “karate” applications did not only come about by way of personal traditions handed down over several generations, but also through the availability and accessibility of videos and illustrations since the dawn of the internet.

There is nothing wrong in optimizing the technical applicability of “karate.” No doubt, it is possible to assign any technique seen in a photo or a video to a posture found in one of the many kata of “karate.” This is an established and successful method. The only issue is whether we want to accept this as an actual historical content of “karate” or not.

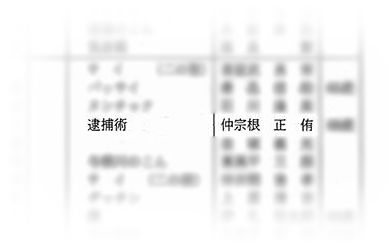

As an example, in 1961, Nakasone Seiyū performed taiho-jutsu (Program of “1st Kobudō Demonstration Meet,” 1961). It is unknown where Nakasone had learned it, and what level of expertise he had reached. The issue here is that Nakasone’s techniques subsequently and generally became considered as a historical tradition of “karate.” This was done without knowing or considering the fact that Nakasone apparently has referred to it as taiho-jutsu, and not “karate.”

Is it not possible that it has had been handed down since the 18th or 19th century in secret?

Is it then not logical that it constitutes a reference technique by which we can see how actual historical karate was like, and from which further deductions about historical “karate” techniques can safely be made?

No, it is not. Rather, Nakasone’s case of taiho-jutsu is an example of how a specific martial arts category was presented within the context of Okinawa “karate” in 1961, and subsequently became considered a historical method of “karate.”

By 1961, almost 100 years had passed since the abolition of the Ryūkyū Kingdom. Also, the term taiho-jutsu provided by Nakasone leaves no doubt that it referred to exactly that, so let’s look at the term.

Taiho-jutsu is a specific martial arts category related to police duties that deals with catching and arresting criminals and offenders. As regards chronology, the term taiho-jutsu came into use only after the end of the war in 1945, as can be verified by a query in the National Diet Library. In fact, it was started in 1947. At that time, Ōtsuka Hironori of Wadō-ryū karate and Shindō Yōshin-ryū jūjutsu was on the team, as well as boxer “Piston Horiguchi.” It was revised in 1957 toward a more efficient learning of the basics of taijutsu, striking, thrusting, kicking, joint manipulation and throwing techniques, but it did not become popular with police officers in the field. Therefore, further research was conducted by the National Police Academy and the current taiho-jutsu was established in 1967. From then until April 1978, 10,000 cases of successful arrests using taiho-jutsu have had been reported.

Today, taiho-jutsu is a method for Japanese police officers, Imperial guard officers, coast guard officers, narcotics control officers, military police officers of the Japan Self-Defense Forces (JSDF), and other judicial police personnel. It is also used by officials who legally speaking are not judicial police personnel, but who perform duties similar to it, such as immigration officers, and generally persons who control, arrest, detain suspects and criminals and take them to the police.

Seen from a broader bird’s eye view, taiho-jutsu is a modern variant of something much older, namely torite and similar jūjutsu-like system with special emphases. Officials, employees, and contractors who have learned martial arts and carried out police duties existed for a long time, and torite already already existed in the Muromachi period (1336-1573). Not only bare hands were used, but also arresting tools such as the “three tools” (sasumata, tsuku-bō, and sode-garami), wooden arrows, the “nose twitch” (hananeji 鼻捻) – a short stick with a cord loop, called like this because it looks similar to the nose twitch used for horses –, and weighted chains (kusarifundō). In the middle of the Muromachi period (1336-1573), the short, hooked truncheon jūtte was used by policemen and private thief-takers, and the techniques of the rope used for restraining criminals (hojōjutsu) also developed.

In the Edo period, martial arts spread to people such as kyōkaku (person acting under the pretense of chivalry while participating in gangs and engaging in gambling), townspeople, landowning merchants, and farmers. In addition, people of discriminated social status were often involved in tasks such as chasing down and capturing criminals or as prison guards, and also to execute punishments and in some feudal domains they had to serve as border guards, in which case they were trained by high-ranking feudal retainers of the domain. In this way they also learned various jūjutsu-like systems, hojōjutsu, and the like.

In any case, as can be seen in the case of Nakasone and taiho-jutsu, martial arts methods and techniques from elsewhere came to be integrated in “karate,” backdated as if they were contents of “historical karate,” and cumulatively placed within the infinite variety of existing “karate” syllabi, and henceforth practiced and considered in reference to “karate,” its kata, and its historical narratives.

In fact, the above is an example of what has become the standard procedure of incorporating other martial arts techniques into karate, and their embedding and historical authentification by referencing it to karate, its kata, and its historical narratives.

© 2022, Andreas Quast. All rights reserved.