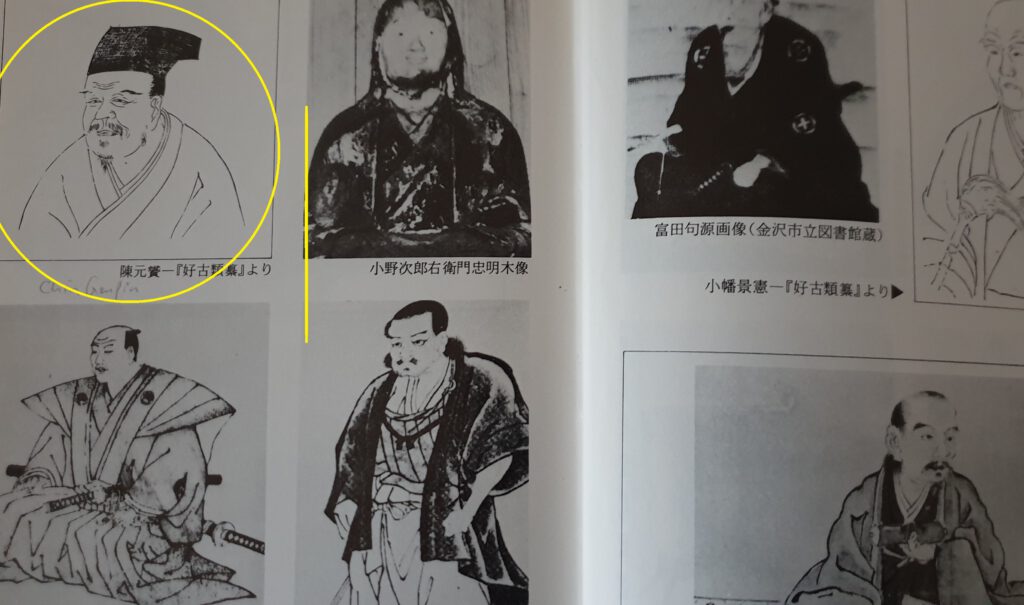

As has been noted previously, it was no less than Itosu Ankō who “said that karate was introduced by Chin Genpin.”

As regards the art taught in Japan by Chin Genpin, it has been described as the “art of torite” (torite no jutsu) as well as kenpō (cf., the entry for Genpin-ryū in the Bugei Ryūha Daijiten 1963 and 1978), approving the contextual interchangeability of both terms. It should also be noted that while China at the time had no regular police force and these techniques were part of the military sphere of wu in general, in Japan it had been interpreted into techniques for persons who were feudal policemen rather than warriors at that time already.

Another hint is given by kobujutsu expert Taira Shinken, who might have picked up Itosu’s note, stating that “about three hundred and eighty years ago, a certain Chinese person named Chin demonstrated a kind of arresting art to police officers, which subsequently were adopted and further developed.” Obviously, the Chinese martial artist in this note is Chin Genpin, the arresting art is given as taihojutsu – i.e. the modern equivalent of torite in sense of a police martial art to arrest criminals –, and the police officers are described as torite no yakunin, that is, feudal officials specialized in arresting criminals. (Taira 1997: 55, from a writing of Taira posthumously published).

One may argue about the validity of Itosu’s reference to Chin Genpin. However, it is symptomatic for karate’s narratives to be extremely selective and artificial in their tendency to almost never even consider Japanese influence, but instead always quickly refer to China. The reasons for this are manyfold. One reason is to protect the overall popular narrative of Okinawa as having been historically victimized by Yamato/Japan. The whole modern narrative of Okinawa largely depends on not referring to Japan. Also, among martial artists there is a lack of theoretical and practical knowledge of historical jūjutsu and its technical contents and distribution to a degree that most of the masters can be said to have no clue about it. It is therefore no wonder that everyone quickly sidesteps such issues and instead perpetuates whatever they can relate to without further efforts. In the end, most of Okinawan karate is based in kata of the early 20th and late 19th century at best, and on personal traditions among Okinawan persons, while various historical martial arts of Okinawa have obviously been lost. This raises the question whether or not karate is an invented martial art of the 20th century. I cannnot imagine that any one of the countless people who have huge stakes in the modern narratives and success of karate will entertain that idea.

And hence, the fact that Chin Genpin was mentioned as a headwater of karate by the real father of modern karate, Itosu Ankō, which was noted for the purpose of further study by Majikina in 1923, has almost entirely been left unconsidered by karate people anywhere for the past century, and continuing. Keep in mind that this is not just about Chin Genpin, whose story was well-known at the beginning of the 20th century in Japan. Rather, it is about the question of distribution pathways of martial arts techniques, and why the stakeholders and agents involved in Okinawa karate obviously refuse to consider it. BTW, to see why Chin Genpin’s (once popular) story of being a founder of Japanese jūjutsu is erroneous and completely exaggerated, see Serge Mol’s Classical Fighting Arts of Japan (2001).

This being said, I am looking forward to more research towards the topic of Japanese martial arts techniques handed down to Ryūkyū, or Okinawa respectively, and whether or not they were simply lost or whether they were possibly somehow incorporated into later martial arts fashions, even if fragmentary. In the end, the existence and use of the term torite (tuitī in Okinawan dialect) alone makes further study indispensable, that is, if interest in karate history is not just mere lip service.

BTW, Itosu mentioned torite in 1908. The next note about torite from within Okinawan karate circles appeared only in the 1960s, more than half a century later.

© 2021 – 2022, Andreas Quast. All rights reserved.