I have owned a facsimile edition of the Ambraser Codex since the erly 2000s. It was expensive but well worth it. The edition was self-published in Prague in 1889 by fencing master Gustav Hergsell, who dealt in detail with Talhoffers work. The work contains 116 plates reproduced in collotype method, of which two pages are text and 114 are picture plates.

According to the description in it, the book was published with approval of the office of the immediate head of the imperial-royal court and household of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, by:

Gustav Hergsell, k.k. Hauptmann der n.a. Landwehr, k. Landesfechtmeister zu Prag, Ritter des kaiserlich Oesterreichischen Franz Josef-Ordens, Besitzer der herzoglich Sachsen-Cobur-Gothischen Verdienst-Medaille für Kunst und Wissenschaft.

Hergsell was an outspoken expert. His dedication inside the book tells about his patron at the time, which refers to Rudolf, Crown Prince of Austria:

Dedicated n deepest reverence, to

His imperial and royal sovereignty,

the most illustrious Highness,

Crown Prince Archduke Rudolph.

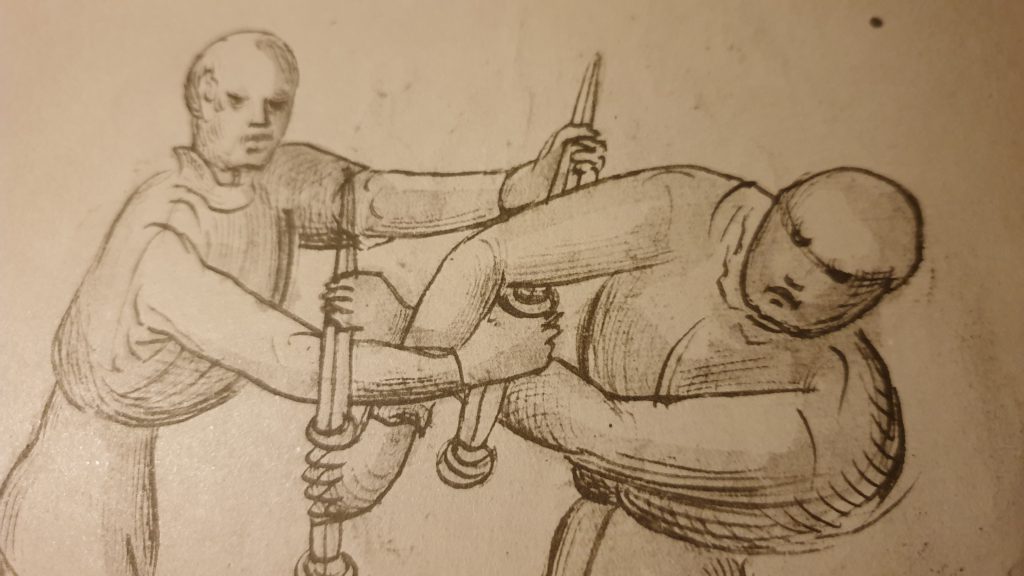

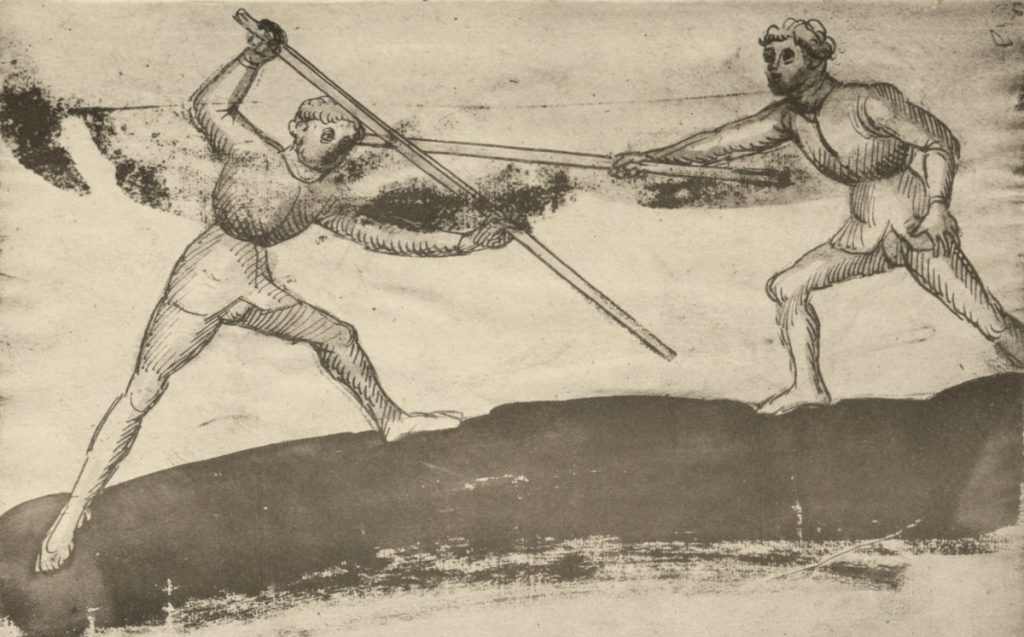

The depictions of the judicial and other duels show the seriousness behind the efforts of the fencing masters of that age. In fact, the larger part of the work itself is a guide to the serious combat, as given by master Hans Talhoffer to the squire Königsegg (Lwtold von Kungsegg) towards a fight for life and death, which is also shown in its various stages, and which ends with the death of the opponent.

Typically for fencing manuals of that era, the depictions seem flawed from an artistic point of view. But they clearly show that the techniques of the ancient fencing masters, particularly in case of Thalhoffer, were designed to kill the opponent. It has been assumed, therefore, that typical distinguishing marks of combat masters of that time would probably have been broken bones, cuts, missing fingers, or a glass eye.

Already in 1754, German legal scholar and politician Johann Carl Heinrich Dreyer (1723–1802) has described the codex in detail. According to it, the original Ambraser Codex contained twenty leaves without the figures, which at Hergsell’s time were not there anymore. In addition to the twenty leaves of text, some of the plates with drawings also seem to have disappeared.

The condition of the codex at the time of Hergsell’s reprint was that of an illustrated manuscript with accompanying explanations, as well as two pages of text. The content was as follows:

- 1. Combat rules.

- 2. Combat with the long sword.

- 3. Duel of Junkers Königsegg in full armor.

- 4. Dagger fencing.

- 5. Wrestling (=unarmed combat).

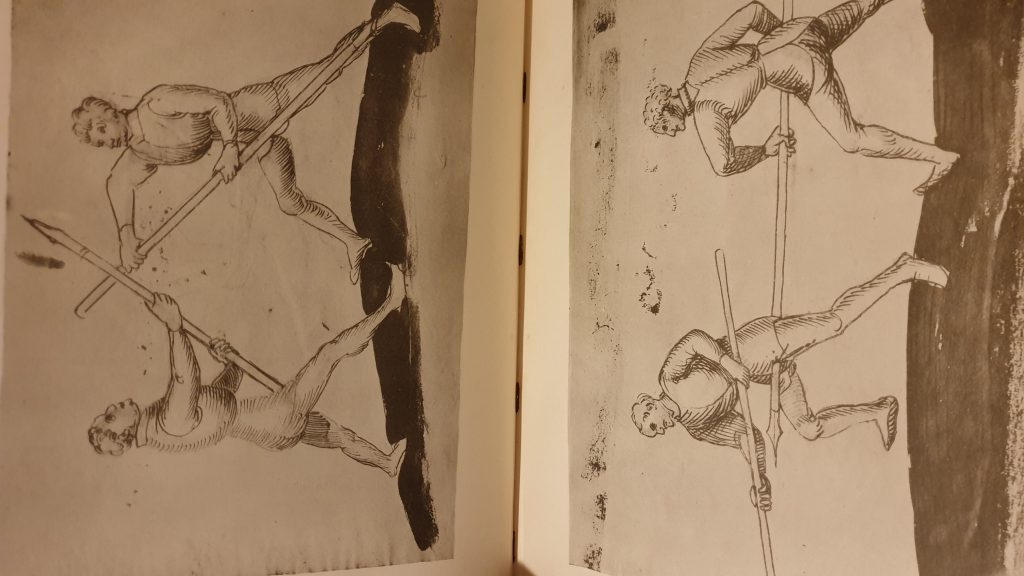

- 6. Combat with the pike.

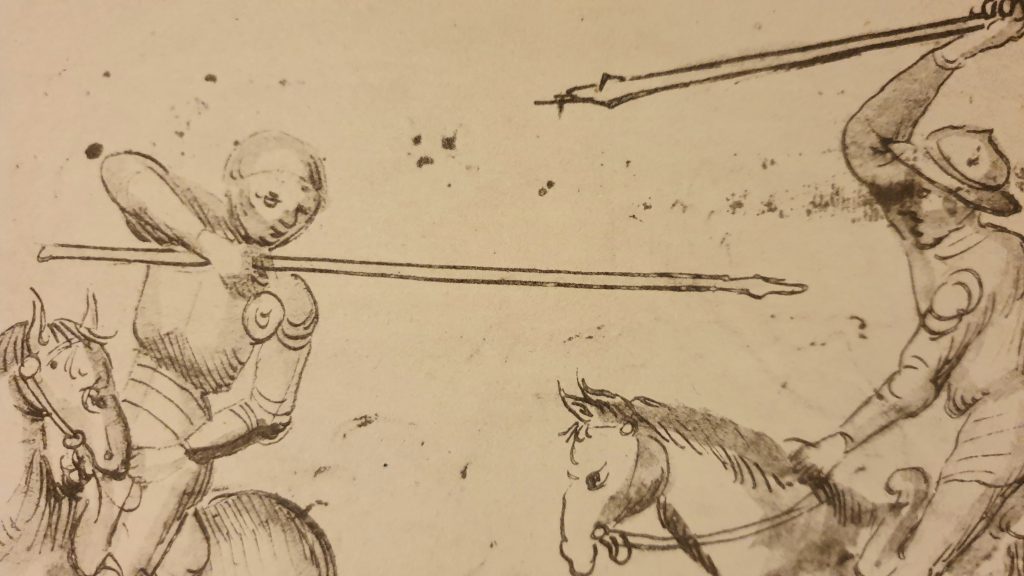

- 7. Mounted combat with the pike.

- 8. Mounted combat with the sword.

- 9. Wrestling on horseback.

- 10. Scenes of horsemanship.

While the work was about serious and deadly combat, there is also one depiction showing combat with staffs. In it, the right fighter strikes while holding the staff with one hand only, in this way making use of the full length and swing of it. The other fight defends by holding his staff inclined, with his head and body behind it.

I’ll end this short piece with a few words about Talhoffer and by sharing a few photos from my edition (right klick and “open in new tab”):

Hans Talhoffer was a 15th century German fencing master. His martial lineage is unknown, but his writings make it clear that he had some connection to the tradition of Johannes Liechtenauer, the grand master of the German school of fencing. Talhoffer was a well educated man, who took interest in astrology, mathematics, onomastics, and the auctoritas and the ratio. He authored at least five fencing manuals during the course of his career, and appears to have made his living teaching, including training people for trial by combat.

Wiktenauer

© 2019, Andreas Quast. All rights reserved.