The “Law of Fifteen Injunctions” as well as the vows taken by king and councilors (sanshikan) were first given in English translation in 1879 in the Japan Daily Herald on 3rd October 1879, three days later again in the Japan Gazette, and on October 16, 1879 in the North China Daily News.

The “Law of Fifteen Injunctions”

During King Shō Nei’s captivity in Satsuma the Shimazu handed to him the Law of Fifteen Injunctions (okite jūgo-jō 掟十五ヶ条). These constituted the basic regulations to be implemented in the Ryūkyū kingdom under Shimazu control. It clearly determined that the Three Councillors (sanshikan) were given administrative responsibility for internal affairs (article 9). Another important point was that Satsuma was to take care of all external affairs (articles 1, 6, and 13). Although not explicitly noted, this included that military protection towards external threads was henceforth provided by Satsuma. And this was the major trigger for the development of the non-military character of Ryūkyū’s security functions and martial arts during the early modern era. Except for the security-related functions within the China trade and duties related to foreign ships reaching her shores, the martial arts of the Ryūkyū Kingdom were henceforth directed inward only.

Dated October 24, 1611, the Fifteen Injunctions were the following:

Art. 1.: No goods other than those authorized by Satsuma shall be taken to China.

Art. 2.: No emoluments shall be given to any member of any family, however illustrious a pedigree he may have, unless he is currently in public service.

Art. 3.: No emoluments shall be given to women.

Art. 4.: No private servitude shall be allowed.

Art. 5.: Shrines and temples shall not be established and maintained in excessive numbers.

Art. 6.: No merchants shall be allowed to engage in trade to or from Ryūkyū without the officially sealed permit of Satsuma.

Art. 7.: No inhabitant of Ryūkyū shall be bought or sold and taken to Japan.

Art. 8.: All annual taxes and other public imposts of a similar kind shall be levied in accordance with the rules and regulations stipulated by the Resident Commissioner of Satsuma (in Naha).

Art. 9.: The conduct of public affairs shall not be entrusted to any person other than the Three Councilors (sanshikan).

Art. 10.: No persons shall be compelled to purchase or sell against his will.

Art. 11.: Fights and quarrels are prohibited.

Art. 12.: Reports shall be made to the authorities in Kagoshima, in case of any official making any unreasonable and unjust claim upon merchants and farmers or others exceeding the amount of taxes and labor duties properly to be levied according to prescribed law.

Art. 13.: No merchant ship shall be allowed to go from Ryūkyū to any foreign country.

Art. 14.: No measure for grains other than the standard measure known as Kyōban shall be used.

Art. 15.: Gambling and all other vicious habits of a like nature are prohibited.

Those who violate these rules shall be put to prompt and severe punishment. We hereby lay down this order.

The Written Oath

King Shō Nei and his Three Ministers had to sign a written oath, which was to proof that the authorities of Ryūkyū felt loyal towards the Shimazu. On the same day the “Law of Fifteen Injunctions” was issued, the king and two of his Sanshikan signed the pledge:

- The kingdom had long been a dependency of Satsuma, but because of its failure in recent years to do its duty toward the overlord, it has been chastised. After the custody in Satsuma, the king and his men were to be allowed by the merciful lord to return home and to govern the territory kindly granted to them. The favors so extended by Satsuma shall not be forgotten.

- These oaths shall be handed down to posterity, so that Satsuma’s benevolence will long be remembered.

- The 15-article edict shall be faithfully observed, and any violation is liable to punishment.

The oath was to be pledged by every subsequent king and councilor (sanshikan). Matsuda concluded that “even in case of any revolt in the kingdom to which their king might lend support against Satsuma, their obedience would always be to the Satsuma lord.” From this reason any sort of rebellion or armed and unarmed resistance would have been completely futile, which should be recalled in connection with the theories of the emergence of Karate.

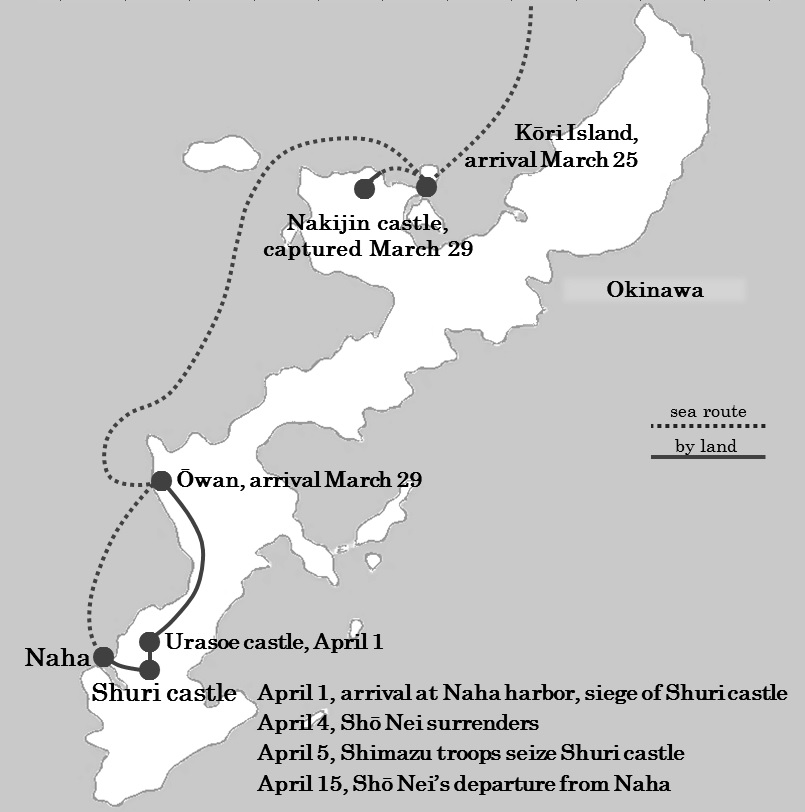

BTW, during the offensive in 1609, after having been repelled from Naha harbor, in late March the Shimazu troops made land in a bay near Unten in the northern part of Okinawa. After disembarkation, Ryūkyū sought a peaceful solution, which was denied. On their way from the north the invading forces took each and every fortress, shooting many of the defending commanders in battle, and in early April captured Shuri castle.

At that time, at the extremely steep area behind Shuri castle the Okinawan defenders had released large numbers of venomous snakes (dokuhebi), so the Satsuma warriors accumulated firewood and brushwood on the ships, transported it to the coast and set the forests and thickets on fire, burning everything down to kill the snakes.

© 2019, Andreas Quast. All rights reserved.