In the legend of Shirotaru, it is said that the fruitful harvest from Kudaka Island was dedicated to the people of Tamagusuku district, who began to brew sacred wine from the crop and offered it to the lord Tamagusuku Aji, and offered it to the gods. As suggested previously, the legend of Shirotaru has also been variously interpreted within the legend of origin of Ryūkyū itself. Let’s take a look at the article called “The Indigenous Culture and Martial Arts in Okinawa” (沖縄の土着文化と武術) by Miyagi Takao (OKKJ 2008: 25).

“Since ancient times, the people of Ryūkyū highly valued their religious beliefs. According to popular belief, in legendary times the ancestors came to Ryūkyū from distant land far off in the sea. They brought with them plenty of food, an original culture, good craftsmanship and so on. This distant land far off in the sea is called Nirai Kanai, the ‘paradise beyond the ocean.’ In hope of a blessed life, the people included gods and celestial beings from Nirai Kanai in their prayers.”

In the legends of origin of Ryūkyū, from this distant land far off in the sea (Nirai Kanai) a pot with five kinds of grains drifted to Kudaka Island. But there were no grains of rice among them so the “legendary god, Amamikiyo, descended and summoned an eagle to Nirai Kanai to get these grains. The eagle traveled a long journey and returned with three grains of rice between its beak. Amamikiyo then planted these grains at a spring in Tamagusuku.” This is how the ancient religious beliefs of Okinawa came into being, reflected in the worship of nature, like Utaki. And the various analogies to the Shirotaru legend are obvious.

I still wonder: What has this supposedly to do with bōjutsu?

Well, according to above quoted article by Miyagi Takao,

“The marine culture established its own entity of existence. Divine assistance paired with the courage of the people shaped the basis for the ‘heart of Ryūkyū’ (Ryūkyū no kokoro). In this way the people of Ryūkyū came into contact with Japan, China, and Southeast Asia, at which the gods of Nirai Kanai acted simultaneously as gods of safe sea voyages, gods of the fine arts, and gods of cultural creation. In the same spirit, the fine arts, karate, and kobudō coalesce into a traditional culture. This is ‘kokoro’, or the spirit of mutual assistance, fellowship, and community.”

Alright. That is, in the 21st century self-perception of karate and kobudō everything is glued together: culture, religion, history, technique, etc. Well, it is a good, sustainable marketing idea. And actually it is quite typical for Japan, where “indigenousness” underpinned by academic or other sources is valued extremely high. The search for “indigenousness” might have been one decisive momentum in the development of karate anyway.

Btw, native beliefs in Ryukyu have been a topic for centuries. Already in 1611 the Satsuma domain ordered the termination of official emoluments for women in Ryūkyū. This aimed at eradicating the influence of the ancient institution of “holy women” in both society and government. While this measure was by no means fully implemented by the Ryūkyū royal government, it led to a gradual loss of influence of the “holy women” at the royal court.

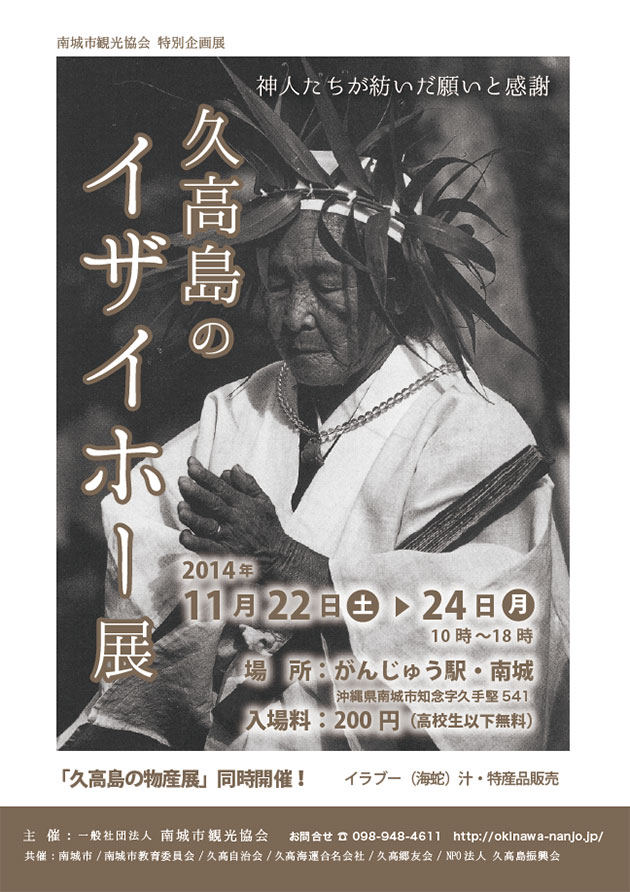

Priestess at Kudaka Island. Poster by Nanjo City Tourist Association.

Haneji Chōshū (1617–1675), prime minister of Ryūkyū from 1666 to 1673, realized that the native beliefs constituted “a conflict between ancient and medieval societies – the former dominated by women and the latter by male statesmen awakened to medieval consciousness” (Nakahara Zenshū, “Koyū Shinkō,” p. 154, cited in Matsuda 2001, p. 87). Haneji struggled against numerous native superstitious beliefs which extended to “illiterate peasant diviners” (called Tuchi), government officials, and holy women within the royal government, representing the dominant religious force of the country. The nation’s chief priestess known as Kikoe Ōgimi was begun to serve as an institution during the reign of King Shō En (1470–1476). At that time, the Kikoe Ōgimi usually was the queen or a daughter of the ruling king, which underscores their high level of official influence. The Kikoe Ōgimi stood on top of a vast network of religious administration and remained in the same official rank as the queen. Only in 1667 Haneji degraded her one rank below the queen. Haneji also criticized the traditional pilgrimages of the king and holy women to holy places in Chinen, Tamagusuku, and Kudaka Island.

Kudaka Island – as mentioned in the Shirotaru legend – is not just some arbitrary island. Quite on the contrary: During the Ryūkyū kingdom era it was an important place in connection with bilateral religious powers of the king and the holy women. In fact, since ancient times the king regularly visited Kudaka Island to worship, such as in 1550, when sacred wine was offered by a specifically designated official (see Kyūyō, article 211). Like this, sacred wine – as mentioned in the legend of Shirotaru – was a regular item of sacred offerings to the gods as well as to the royal family for centuries. To curb religious influence and divining and shaman practices as a whole, such pilgrimages were officially abolished in 1673 and henceforth performed by subordinates of the king. Like this, Yoshimura Aji Chōmei assumed the headship of the Yoshimura family in 1847 and moved into the hereditary family lodgings in Shuri and succeeded the hereditary fief of the Kochihira district, worth 300 koku. In the following twenty-five plus years he served the royal government in a large number of duties. And as a member of the Princely Shō-clan he was also dispatched to Kudaka Island to perform prayers for the nation’s health and security on behalf of the king (cf. Genealogy of the Princely Shō-clan, House Yoshimura). BTW, this person was the father of Yoshimura Chōgi, in turn the noted disciple of Higashionna Kanryō and (cf. Okinawa Karate Kobudō Jiten 2008: 597).

It is therefore interesting how those ancient beliefs survived. In this connection it was rather remarkable when a few years ago a young strong Okinawan martial artists, while openly flaunting his contemptibility, told me “You are Christians, ne?! … But we Okinawans are not religious!!!” The same persons would shiver when I whistled, because – as you know – this calls out the ghosts of the dead…

While I still wonder what this could possibly have to do with bōjutsu, for the time being I’d say: Sapere aude, boys and girls, sapere aude.

© 2018 – 2022, Andreas Quast. All rights reserved.