There is an interesting bōjutsu kata called Shirotaru no Kon. Today there are quite a number and variety of different versions of this kata in existence. Most of them have more in common than not and they all share specific “signature techniques” which unequivocally point to a common ancestor and make it clearly distinguishable from other bōjutsu kata.

There are different ways of writing the name in Japanese kanji and of pronouncing it. In addition, while there is very little tenable information about it, various authors consider it “the most ancient form of bōjutsu” (cf. OKKJ, 2008).

Since many points about this kata remained unexplained, it is a rather confusing topic for persons seeking tenable information, both technically as well as historically.

Well, Miki Nisaburō described Shirotaru no Kon in his work “Kenpō Gaisetsu” (1930, pp.171-181). Within my private studies, I translated the text already years ago and conducted various cross studies, once from literature, and once asking various experts when traveling to Okinawa. Literature was more fruitful.

Miki had learned the Kata from Ōshiro Chōjo (1887-1935), who lived in Shuri Ōnaka 1-54 at the time. At that time Ōshiro served as a regular teacher as well as the head of the karate department at the industrial school (Kōgyō Gakkō), where he taught karate and bōjutsu to the youth in an “educational manner.” He also taught karate and kobudō at the Okinawa Prefectural Teachers’ College (Okinawa-ken Shihan Gakkō), where he was active together with Yabu Kentsū.

As Miki put it,

“Ōshiro was known as a leading man in bōjutsu of today’s Ryūkyū. And the famous bōjutsu master Yamane no Chinen sensei was his teacher.”

Obviously Ōshiro also initiated Miki into heroic tales which, btw, accompany Okinawan martial arts throughout its existence:

“My bōjutsu is based on what I was taught by Ōshiro sensei, and the story (told by Ōshiro sensei) about ‘Chikin Akanchū’ – a person who was very good with the bō – was interesting.”

Ōshiro did not only teach at school but also invited the youth to his private home to teach them, about which they are said to have been “both were happy and proud.”

Well, regardless of today’s many versions, Miki’s classical version of this kata is proof of how Shirotaru no Kon was performed in the 1920s. Or let’s say, how at least one version of it was performed.

Let’s turn to the seemingly easy part first: history.

Nohara Kōei accredits Shirotaru no Kun to a certain Shirotaru Uēkata during the 14th century (Nohara 2007). Uēkata was a rank similar to that of a minister of state.

In the “Okinawa Karate Kobudō Encyclopedia” (2008) it is also said that:

“Shirotaru no Kon is the most ancient form of bōjutsu and the name Shirotaru remained from 1314 (year Ōchō 4) as the name of a warrior who was active during that time.”

Nakamoto (2007: 109) also wrote about the matter:

“Remembered in the whole Shimajiri region as well as in outlying islands, this posture [Shirotaru no kamae] is probably a relic of [the person] Shirotaru [from the legend].”

Indeed, in the Okinawan folk tradition a person named Shirotaru is the main actor of an ancient legend. The legend is described in the Irōsetsuden [*1] and the Kudakajima Yuraiki [*2] .

The Legend of Shirotaru

A long time ago a young boy called Shirotaru lived in Hyakuna Village in Tamagusuku District. Due to his docile nature and pronounced filial piety, Shirotaru was deeply beloved by Tamagusuku Aji, the lord of the district. So the lord married Shirotaru to the daughter of his eldest son, Minton Aji, thus making Shirotaru his grandson-in-law.

One day, Shirotaru and his wife went out in the fields and saw a small island alternately appearing and disappearing in the eastern sea. At that time, local warlords rivalled for power and there was war without end. The couple imagined how much better it would be to avoid the war and instead to cross over to the island and live together enjoyably, and so they crossed over to the island in a small boat. They saw clear spring water gushing forth, fertile soil, and fields far and wide. It was a comfortable place to live. They built a hut and stayed on the island.

The two made their living by gathering conch shells. One day they discovered a white jar that came drifting in the sea. Shirotaru tried to catch it but every time it disappeared between the waves and could not be seen. His wife had a revelation and so they went to the Yaguru Well where they performed a ritual ablution for purification. Afterwards they returned to the shore and this time Shirotaru was able to get hold of the jar. When they opened the lid they found seeds of the five grains in it. At once they choose the right soil, sowed the seeds, and it produced fruitful harvest, which the couple dedicated to the people of Tamagusuku district. Everyone greatly rejoiced and immediately began to brew sacred wine from the crop and offered it to the lord Tamagusuku Aji, and offered it to the gods, and gave it to the retainers and commoners. Since that time, the descendants prospered and the island was named Kudaka 久高, referring to the abundant harvest of the five grains over many years from this island in the sea.

One boy and two girls were born to the couple. The second daughter Umitaru 思樽, since she was a rare beauty, was summoned by Tamagusuku Aji and entered the inner sanctum of the castle. She attracted the affection of the lord but also the jealousy of many of the other concubines. One day Umitaru farted in the presence of lord Tamagusuku Aji, thus breaking manners, and so she was expulsed back to her birth-place Kudaka Island.

At that time she was pregnant and gave birth to a boy during full moon and named him Kanematsu 金松. After Kanematsu had grown up, he did not stop to frequently ask about his father. Eventually his mother explained to him the situation.

One day, Kanematsu found a jar at the shore. In it he found golden gourd seeds. Overjoyed he immediately went to the castle and presented the seeds to lord Tamagusuku Aji. While presenting the seeds he said

“When a merciful rain rains down, have a woman who has never even farted once in presence of her husband sow these gourd seeds. Be that the case, it will bear fruits of gold!”

The lord Tamagusuku Aji smiled and replied

“There cannot be a woman in the world that never farted.”

So Kanematsu responded,

“Then, why did you expel my mother because she has farted?”

Thereupon Tamagusuku Aji regretted his past follies. Later, since he had no heir, he made Kanematsu his heir.

Above-mentioned Kanematsu was identified as King Sei’i (西威王, 1328?–1349; rg. 1336 or 1337 to 1349), the 5th generation descendant of King Eiso 英祖王 of the Eiso Dynasty (1229–1349). When he died in 1349, his 5-year-old heir was dethroned and went into seclusion to Kudaka Island.

In the land near the Shuri castle there lived a House Kudaka of the Kei-clan (恵姓久高氏) who were descendants of Kanematsu=King Sei’i and who served in the position of priests called the “Shuri root deity 首里大根神,” which must have been an important religious post. During the Jingtai years (1450–1456), 1st generation founder Kudaka Pēchin Yūken 久高親雲上友顕 was officially appointed estate steward (jitō) of Kudaka Island territory by the royal government in Shuri. In 1671, during the era of King Shō Tei (1646–1709; rg. 1669–1709), the 8th generation Kudaka Pēchin Yūjō 久高親雲上友常 became a clerk of the Omono Bugyō of the government of Naha. 10th generation Kudaka Pēchin Yūshi 久高親雲上友始 was granted the post of the estate steward (jitō) of Kudaka Island as a hereditary domain.

Assessment of the Shirotaru Legend

Well, in the legend, Shirotaru was not a warrior. Quite on the contrary: he was someone who left the war behind with his wife to live on a peaceful island. Moreover, the original legend never mentioned any kind of bōjutsu, let alone the “most ancient form of bōjutsu.”

What, then, could this have to do with pole fencing techniques?

So lets seek out the narrative coherence in the tradition of Shirotaru no Kon:

According to our written source from 1930, Miki learned his bōjutsu from Ōshiro, who in turn learned it from Yamane no Chinen. For those of you who are into lineages and know a little about the importance of a chronology of events, the earliest source I was able to detect which adopted this information in written form was Inoue Motokatsu who wrote in 1972 (page 6) that Shirotaru no Kon was created by Yamane no Chinen (1842–1925). Ōshiro also initiated Miki into the heroic tale of Chikin Akanchū (a person who lived on Tsuken Island). Now, in the tradition of Shirotaru no Kon, it was noted by Nakamoto Masahiro (2007: 109):

“Having remained on Kudaka Island as Shirotaru no Kon, the founder of Yamane-ryū, Chinen Chikudun Pēchin Masanrā, at the age of 18 years heard that there are masters of bōjutsu on Tsuken Island and on Kudaka Island. So he went to both these islands to learn the bōjutsu.”

Here, a late 19th / early 20th century oral tradition of Yamane no Chinen is further backdated to the 14th century. The connection is made by regions (Tsuken and Kudaka Islands) and by the existence of a “back guard” in this kata and — last but not least — by the name of a legendary person called Shirotaru. Well, it is possible. However, there are a number of other options which are at least as possible as the above. And the blending of existing historical facts and legends with martial arts stories is a typical narrative method of karate and kobudō circles.

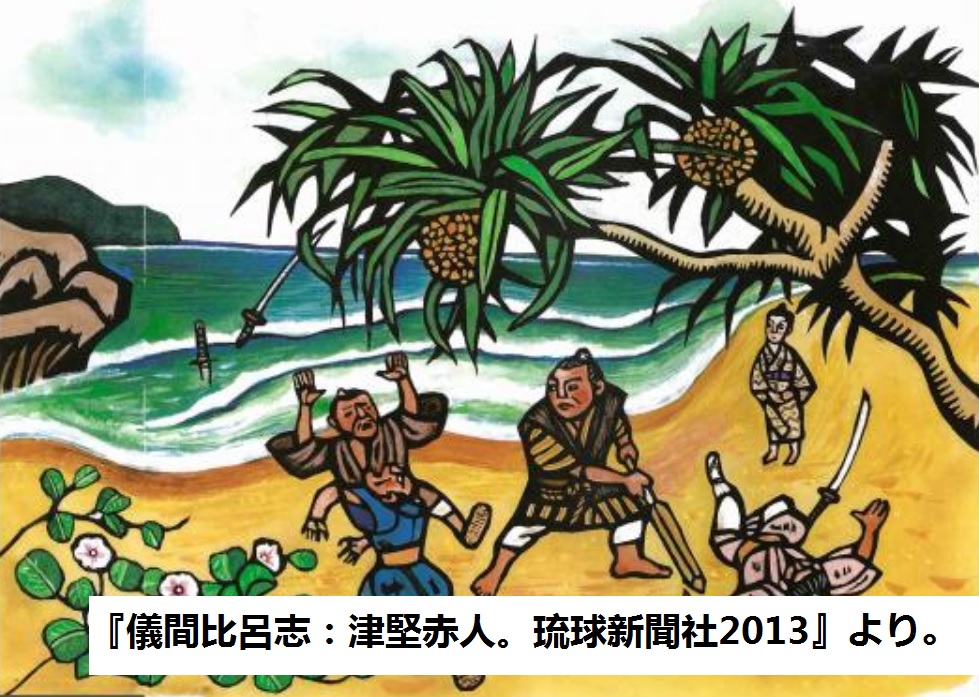

Depiction of the scene from the life of Chikin Akanchu. From: Gima Hiroshi: Chikin Akanchu. Ryukyu Shinpo 2013.

Well, it is an interesting legend, a number of variations of which are found today on Okinawa. It should be noted that the “five grains” as mentioned in above legend is something that was already mentioned 600 years earlier, namely in Japan’s oldest historical record called Kojiki (Records of Ancient Matters, 712 AD). The whole legend with its references to ritual ablution, divine assistance in providing food (the five grains), the role of the Yaguru Well [*3] which still today is used by Noro (Okinawan: Nuuru) priestesses of the ancient Ryūkyūan religion for ritual ablution: This is a strongly religious legend, combined with prayer for good harvest etc. In some versions Shirotaru and his wife are even presented as two deities and children of gods send down to earth.

Rather, it is also possible that, just as in other cases (Kūsankū etc.), that a documented historical event served as the godfather and namesake of a new cudgel fencing method, part of whose narrative design principles it was that it had to be rooted in indigenous history.

While all this is up to speculation, I will turn to the technical description of the kata in a latter part of this series.

Notes

[*1] Tei Heitetsu (1695–1760) compiled the Kyūyō 球陽 as well as the Irōsetsuden 遺老説伝, both written in Chinese. Kyūyō is a poetic name and refers to Ryūkyū itself. The book is a semi-official history of Ryūkyū. The Irōsetsuden is an adjunct volume to the Kyūyō and features ancient legends. See: Matsuda 1962.

[*2] “Account of the Origin of Kudaka Island.”

[*3] Yagurugā ヤグルガー (屋久留川). ~gā ガー here means “well.” It is located in Kudaka, in the Chinen section of Nanjō City, Okinawa Prefecture.

© 2018 – 2022, Andreas Quast. All rights reserved.