More than one century has passed since the creation of karate 唐手 in 1905. About seventy-five years ago, in 1936, karate 唐手 was renamed to karate 空手. Since I have had made karate 唐手 my life-task in 1926, about eighty-five years have passed through the three eras of Taishō (1912–1926), Shōwa (1926–1989), and Heisei (1989–). And so I lived in this world throughout the greater part of the history of both karate 唐手 and karate 空手. When looking back on my long karate life, I strongly feel that it was a series of really fortunate coincidences.

I survived difficult-to-cure diseases, begun with meningitis and pneumonia during my childhood days, as well as pulmonary tuberculosis and typhoid fever as an adolescent. Reaching my young adulthood, after about five years in military service and having narrowly escaped death, I was repatriated. Having reached an old age, I also survived lung cancer. Today, at more than 90 years of age, and despite having a variety of adult diseases, I—by and large—enjoy good health and spend every day in peaceful gratitude with reading, exercising, and writing. I also think I lived a little longer than expected.

From childhood to young adulthood I was able to meet most of the people that are referred to as the prominent figures and masters of karate 唐手 at the time (to be precise, the Shuride of that time). In addition, by an integrated analysis of the fragmentary teachings by each of the aforementioned masters, and furthermore through a comparison with the literature related to karate 唐手 of that time, I was able to roughly understand the true picture (real-life image) of the techniques and the historical facts of karate 唐手. However, I guess the image of karate 空手 among the general public is something considerably different.

I feel a sense of duty to by all means communicate to future generations the true picture (real-life image) of karate 唐手 that I have obtained, thus filling in the blanks in the history of karate 空手. Especially as regards handing down our ancestors’ teachings I have the profound feeling that my own life is not solely mine alone [Note: in sense of owing to the masters].

In 1905, nascent karate 唐手 as a compulsory subject entered the regular curriculum of Okinawa Prefectural Middle School and Okinawa Prefectural Teachers College. Because it was the first attempt by the prefecture, the educational outcomes of karate 唐手 were tried out at the Middle School. In addition to this, Itosu Ankō, as the person responsible for karate 唐手 instruction, reported back ten individual clauses. His written report of ten clauses are the so-called “Itosu Ankō’s Ten Articles of Karate 唐手.” However, because of its contents, I promote it under the name “Itosu’s Ten Maxims (Itosu Jikkun),” as a “holy book” advocating the spirit of respect for human beings. Without knowing “Itosu’s Ten Maxims,” it is impossible to talk about both karate 唐手 and karate 空手.

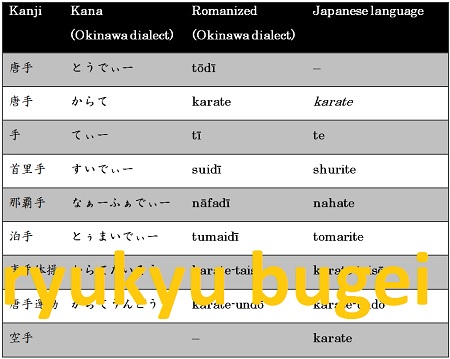

What is the difference between Todi, Karate, and Karate?

Since the creation of karate 唐手 about one century ago, its name has been changed from karate 唐手 to karate 空手, and by borrowing the [Western] method called “sports competition” (kyogi 競技), its rapid expansion up to a global scale was brought about. The global karate 空手 population is said to amount to fifty million people. Born with a strong local flavor in one solitary island of the southern ocean, who would have expected today’s global prosperity of karate 唐手? Of course, karate 唐手’s development and spread to the global scale is something one should be pleased with. However, I also cannot be happy about it with all my heart. Because it was a course of rapid spread and development, isn’t it likely that important things were left disregarded? What are these things left disregarded? Frankly speaking: they are spirit and tradition.

What is the spirit of karate 唐手?

It has been shown in Article I of karate 唐手’s original text, “Itosu’s Ten Maxims,” that

“…by word of honor, (the quintessence should be) to never injure human beings by means of one’s fists and feet.”

This is the philosophy of peace, with the spirit of respect for human beings as its keynote.

What are the traditional techniques?

In Article VI of “Itosu’s Ten Maxims” it is said that

“…the methods of entering, receiving, disengaging, and the seizing skills, of which there are many oral instructions.”

So the traditional techniques are techniques of oral instruction (orally instructed, i.e. in personal teaching). In due course I will inform you about these techniques of oral instruction as well.

In accordance with the spirit of karate 唐手, antisocial or inhuman techniques within the framework of the fourteen kata were modified or deleted. Notwithstanding, in the karate 空手 tutorials from the world of the ordinary people, techniques such as poking the fingers into an adversary’s eye or dislocating the jaw are introduced. A quite provocative text can also be found, called “One strike, certain kill” (ikken hissatsu). Such absurd remarks are unrelated to karate 唐手, which was created for the purpose of school education.

Within its development and spread to a global scale, karate 唐手 in technical terms has also been discovered as a combat sport (kakutōgi) ever more. However, it is difficult to determine whether these techniques were newly developed, or are techniques of karate 空手, or are techniques borrowed from other combat sports. In the transformation from karate 唐手 to karate 空手, the framework of the fourteen kata has been forgotten. Karate 空手 has become something which only is reminiscent of karate 唐手 in appearance. Strictly speaking, karate 空手 has even become something like the kata of Chinese kenpō. This might appear like rushing to conclusions. But in its current form, there is no way around it that karate 空手 is being criticized and dismissed by the circles of scholarship and logic.

As for me, it is not the case that I wish for the revival of karate 唐手 by karate 空手. It is also not my intention to denigrate karate 空手. Rather, in order to understand the true nature of karate 空手, and furthermore to support its rich future prospect, I think it is necessary to correctly recognize the history of the creation of karate 唐手. This is especially true as karate 空手 is one of the contemporary budō (gendai budō) which will be introduced as compulsory subjects in the middle schools, starting in the school year 2012. What must be taught through the practice of karate 空手? What must be learned? It would be a blessing if this book of mine would become a good guidepost for karate 空手.

August 2011

Kinjō Hiroshi

Biblio:

Kinjō Hiroshi: Karate kara Karate made (From Karate to Karate). Nippon Budōkan, Bēsubōru Magajin-sha, Tōkyō 2011. 439 pp. 20cm. ISBN: 9784583104294.

Translation by Andreas Quast.

© 2017, Andreas Quast. All rights reserved.