The article “Karate no omoide” (My Memories of Karate) is a primary source about Kyan Chōtoku’s life and his relation to karate. The article was published on 1942-05-07 in the Okinawa Shinpō Newspaper.

The Okinawa Shinpō was a result of the nationwide “newspaper control regulation” (shinbun tōsei), implemented by the Department of Interior (naimushō) and the Information Office (jūbōkyoku) at its center. Its object was the integration of all existing newspapers in such a way so that there is “one prefecture, one newspaper.”

In other words: media was synchronized for propaganda purposes.

In Okinawa, the newspaper control regulation was in effect from 1940 to 1945. It resulted in the establishment of the Okinawa Shinpō Newspaper in December 1940. To do so, three newspapers were integrated into the new one, namely the Ryūkyū Shinpō, the Okinawa Asahi Shinbun, and the Okinawa Nippō.

Even after the start of the ground war on Okinawa Main Island in April of 1945, the Okinawa Shinpō continued to be issued from an underground air-raid shelter in Shuri, but was disbanded on May 25, 1945.

![“Karate no omoide” (Memories of Karate) [excerpt], by Kyan Chōtoku. Okinawa Shinpō, 1942-05-07.](http://ryukyu-bugei.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/011-150x150.jpg)

“Karate no omoide” (Memories of Karate) [excerpt], by Kyan Chōtoku. Okinawa Shinpō, 1942-05-07.

This old Ryūkyū Shinpō was established in 1893 by former ruling class members Shō Jun (1873–1945, 4th son of former King Shō Tai), Takamine Chōkyō (1869–1939, 1st president of the Okinawa Gingko bank), and Ōta Chōfu (1865–1938).

As stated in the first issue (1898) of this old Ryūkyū Shinpō, the objective of this newspaper was

“To strive for national assimilation, to smash the narrow-minded and evil local customs and to hound out regional insular provinciality.”

Make no mistake: The old Ryūkyū Shinpō was very successful in achieving this objective. For this reason it was also referred to as the “agency paper of the ruling class.”

Above mentioned Ōta Chōfu, as the president of the Ryūkyū Shinpō at the time acted as the sponsor and interviewer at the famous 1936 “Meeting of Karate Masters.” The records of the meeting were subsequently printed by his newspaper (see for example, the translation by the Haiwaii Seinenkai, were his name is misspelled to Ota Choshiki).

Ōta Chōfu is a prominent figure within the apolitical self-narrative of modern karate romance. He also provides an example of the diremption of Okinawan society, and karate. While karate today is narrated as a martial art of peaceful people from an ancient peaceful kingdom — with peaceful bitter melons and peaceful baby pork hoove snacks and peaceful everything –, and while there is no first attack (!) in karate, Ōta Chōfu and karate men of his time fully supported Imperial Japan. They did not support any cultural, lifestylish, or peaceful Okinawa.

As regards Ōta, he was one of the first Okinawan students to obtain a scholarship to study in Tōkyō and received a decidedly Japanese – not Okinawan – education. In 1931 he served as the mayor of Shuri and as Okinawan representative in the prefectural assembly.

In his journalistic idea, Ōta focused on the 1st Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895), in which Japan was victorious and which ended the Ryūkyū Question, i.e. Chinese claims on Ryūkyū. This war also ended the Ryūkyūan fight for restoration of the kingdom. And it also brought Taiwan under Japanese control, were it remained until 1945 and were many karate men would serve or tour, including Kyan Chōtoku. This was one of the most crucial events in the making of modern Okinawa Prefecture, and modern Japan!

Ōta, together with 4th prefectural governor Narahara Shigeru 奈良原繁 – nicknamed the “King of Ryukyū” and practitioner of Jigen-ryū sword fencing – orchestrated the oppression and ultimately the destruction of the person Jahana Noboru (1865–1908), the then leader of an Okinawan movement for democracy.

So while Ōta is often portrayed as some nice karate-related guy, his idea of karate was not that of a peaceful Okinawa that never attacked anyone else, but that of the Japanese conolianism, imperialism, and militarism of his time.

Until the time of the “newspaper control regulation” in 1940, the proprietors of the old Ryūkyū Shinpō were all wealthy persons who worked together with the prefectural authorities in achieving national aims while following the editorial policy of “worshipping the powerful” and oppressing the Okinawan civil movement for democracy.

And this political viewpoint can clearly be seen in the (at least) 124 karate-related articles that the old Ryūkyū Shinpō published between 1898 and 1940 (unpublished survey by this author).

It was in the above circumstaces that the Okinawa Shinpō Newspaper came into being in December 1940. “Karate no omoide” (My Memories of Karate) by Kyan Chōtoku was published on 1942-05-07. The text is organized as follows:

■ The Way of Karate

■ The Purpose of Karate

■ Techniques of Victory or Defeat

■ The Method of Unrestricted Offense and Defense

■ The Preparation of the Practitioners

■ The Necessity of Physical Strength

■ Musular Accordance

■ Age and Physique of the Practitioners

■ Chīshī and Makiwara

■ Conclusion

The largest part of the text is about karate and related topics. However, in connection with the earlier mentioned role that newspapers played in Imperial Japanese war propaganda, it is interesting to read Kyan’s conclusion:

■ Conclusion

“I have attained a long life of seventy-three years and yet I have achieved nothing for our society. Here I have written down my memories of karate, making my own essay available to the public, shamelessly. But meanwhile, unfolding from the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) to the Greater East Asian War (1941–1945), the divine spiritual powers of officers and men of the Imperial Japanese Army suddenly appear in the sky and at sea and scatter our huge Caucasian enemies like one unified body. The fruits of battle are based on the glorious virtues of the Emperor, and our officers and men have enhanced the deepest secrets of Bushidō – the Way of the Warrior. Meanwhile, it is unbearable for this old man, to sit here, like an old tree, comfortably next to a charcoal brazier.”

It almost sounds like a reference to Pearl Harbor… On the other hand, the conclusion of the article might have been written under consideration of tatemae (façade towards the public). Moreover, it was not a free society in those days and there was a strong wartime censorship — Like in today’s North Korea. This can also be noticed in Mabuni Kenwa’s and Nakasone Genwa’s books. So one might argue that Kyan said what he had to say.

However, Kyan’s ardent admiration for militarism during the escalating war, and his grief for being too old to participate himself, which clearly aims at moral mobilization of the readers, and all that just 5 months after Pearl Harbor: this does not sound to me as if there was “no first attack in karate.” It does not sound to me like the ingénue, peaceful, old former aristocratic karate master.

To be honest, I wonder how much of Kyan’s karate was really still something “original Okinawan”…

The above was an erstwhile reality of karate. But for how long?

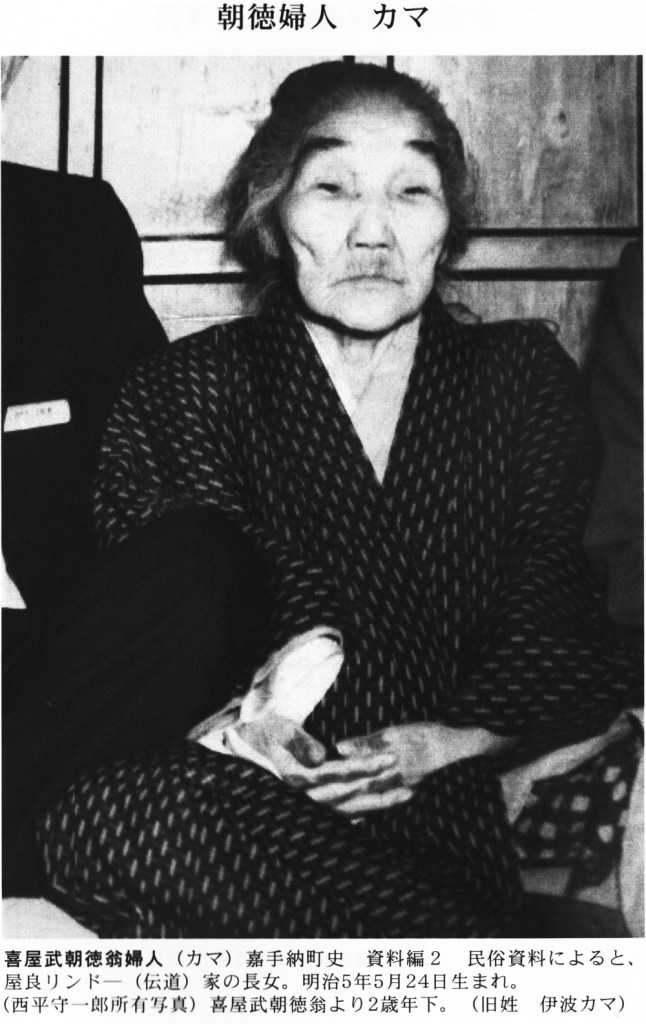

Kyan Chotoku’s wife Kama. Was it all her fault?

There is a terminological problem related to it, namely the timeframe referred to as senzen 戦前 in Japan, literally “the pre-war days”. This term is standard Japanese historical terminology and also used extensively in karate literature. It is sometimes still used for 1941, sometimes for 1942 and basically rethorically narrows down the war years to a very few years, sometimes — and especially in connection with Okinawa — only to 1945. So from the self-narrative of Okinawa karate, December 1944 might well have been considered the pre-war years. What do the Hawaiians think of this?

By this, the term narrows down not only the timeframe, but also the significance of the related, factual military history – and whatever personal opportunities, responsibilities, actions, or inactions related to it. And this is a bit too ambiguous to be helpful, quite on the contrary.

Okinawan soldiers, occupying forces, policemen and business men etc.pp. roamed all of Southeast Asia since the 1st Sino-Japanese War (1894-95), and many of them were karate men. And — as can be seen in his own words — Kyan admired military expansion and would have loved to take part.

Therefore, and particularly to better assess Okinawa karate under the actual circumstances of the time, and moreover to draw a line between the actual “prewar years” and the “war years”, a definition of the timeframe is necessary. And this timeframe of the “war years” should include the years 1931 to 1945 — from the Asia-Pacific War which started with the Japanese invasion of Manchuria (September 1931), via the 2nd Sino-Japanese War (1937), Pearl Harbor (1941) until 1945 (Okinawa). Because it is impossible that these events had no impact on Okinawa, its people, and karate.

© 2017 – 2020, Andreas Quast. All rights reserved.