It would be a mere rethorical question to ask if historical Ryūkyūan combative methods were influenced by the outside world. Notwithstanding, somehow this seems to be a weird question. One of the persistent beliefs making Ryūkyūan combative methods so likable is the notion of their perceived immaculate conception, so to speak, unrelated to serious topics like soldiers, or war. While Chinese influences are considered fully acceptable, Japanese influences prior to 1879 already blow a breach through the atomic lattice of the community.

But what about 19th century Western influences?

Already since the middle of the 17th century the top-ranking official (karō) of Satsuma sent numerous directives to Ryūkyū pertaining encounters with Western ships. As a result, Ryūkyū was strategically aligned to act and represent itself towards foreign visitors in prescribed ways. Ryūkyū’s uncertain position within the complex system of shifting powers at that time can be detected in the narratives of Western visitors. The Ryūkyūan perspective, on the other hand, is reflected in numerous entries in the Kyūyō and the genealogies. These events, especially those of the 19th century, are quite important to understand Ryūkyū’s significance for the Japanese national order, which parallel to these events became more and more unstable. Consequentially, the Western advances of the 19th century had major repercussions on security-related issues in the kingdom. In fact, it probably had major repercussions on the very characteristics of the combative methods of Ryūkyūan design.

Western interest in Ryūkyū became forcefully renewed from around 1800 until the 1850s, when the Western powers–while spreading out at the Chinese coastal areas–tried to break open the isolation of Japan. The first eye-witness report of a Western encounter with Ryūkyū after Wickham and Adams (1614/15) is given by Jean-François de Galaup de la Pérouse, who made land near the island of Yonaguni on May 5th, 1787.

From the beginning of the 19th century the Napoleonic wars led to a decline of European activities in the Far East. But early in 1816, Basil Hall was appointed commander of the Lyra, a small sloop equipped with ten cannons. Together with the frigate Alceste of Captain Maxwell, they reached “the Great Loo-Choo Island” (Okinawa) on September 16th, 1816, and let go anchor in the harbor of Naha. In his narrative Hall provides the first Western note on “karate” (“a boxer’s position of defence”).

One of the Ryūkyūan officers, “a man of dark and peculiar aspect,” was fitted by the British of Hall’s squadron with the nickname Buonaparte, “so named because he was suspected of being the most inclined to keep us at arm’s length.” On his return journey from Okinawa to England, on August 13th, 1817, Basil Hall entered St. Helena, where the real Napoleon I. Bonaparte lived in exile. He reported that Napoleon was most astonished by the information that the Ryūkyūans did not possess weapons.

In the following years the picture created by Hall and members of his fleet portraying Ryūkyū as a weaponless country was relativized. In 1819, on the basis of the travel accounts provided by Hall, Maxwell, and Clifford, a certain Amicus concluded that “Both sides were acting an artificial part” and that the observations of the voyagers were “very limited, and whatever lies the people of Loo-choo chose to tell, the English had no means of detecting them,” pointing to the circumstance that the Ryūkyūans declared that they “had no weapons, not comprehend the use of a weapon, nor had an occasion for the infliction of punishment.”

One of the chief objects of Beechey, who stayed in Naha from the 11th to the 25th of May, 1827, was to inquire into the “supposition that the inhabitants of Loo Choo possessed no weapons, offensive or otherwise.” Inquiring about the weaponry on Beechey’s ship, a Ryūkyūan official inquired,

“Plenty guns?”

- “Yes.”

“How many??”

- “Twenty-six.”

“Plenty mans, plenty guns! What things ship got?”

- “Nothing, ping-chuen” [bīngchuán兵船, man-of-war].

“No got nothing?”

- “No nothing.”

“Plenty mans, plenty guns, no got nothing!”

Anytime foreigners reached Okinawan waters, such inquiries were made, and without doubt forwarded to Satsuma.

Later Beechey was told by a mandarin, and several other persons, that there were both cannon and muskets in the island; and one of the interpreters distinctly stated there were twenty-six of the former distributed among their junks. According to Beechey, the fishermen and all classes from Naha were familiar with the use and exercise of their cannon, and the Ryūkyūans were particularly interested in the improvement from matchlock to flintlock. Elijah Coleman Bridgman, publisher of The Chinese Repository, in 1837 also noted that military weapons and various modes of punishment were prevalent in Ryūkyū.

During Bowman’s stay on Okinawa in 1840, he was once informed by an alarmed principal that “a number of bad men had arrived, to get all the people within the inclosure, and on no account to allow any one out, as he could not be answerable for their safety.” The visitors were described as “Tokara men,” which was the usual Ryūkyūan description of Satsuma samurai towards Westerners.“A short distance, about 100 yards from our enclosure,“ wrote Bowman, “the Tokara men had collected, and evidently several of them men of rank; they were all armed; every man had two swords and a matchlock, or bows and arrows. […] These men were evidently soldiers; each wore a dark-blue handkerchief tied around the forehead, and differently dressed to the Ryūkyūans. I should say they amounted to between three and four hundred in number.”

In a letter of the year 1850, Bettelheim described his discovery of a Japanese garrison quartered in Naha, with “Japanese soldiers engaged in cleaning and polishing their fire-arms.” Some years later John M. Brooke, naval scientist and educator, for the year 1859 noted that “The fathers told us that in their rambles they frequently met Japanese soldiers wearing two swords; that they had seen them with their own eyes and there could not possibly be a doubt of the facts; that the reason we never encountered them was that they concealed themselves the moment we approached them.”

The above are just a few examples of a corpus of evidences that render it completely impossible to pretend as if the shōgunate in Edo and the daimyō of Satsuma had been unware or indifferent towards the Western advances in the 19th century. Ryūkyū, it appears, acted as a clandestine outpost and gathered intelligence for Satsuma, and Japan.

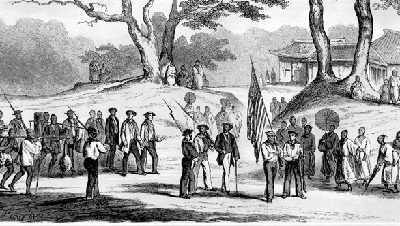

The 18th Royal Irish Regiment of Foot storming the Amoy forts during the 1st Opium War.

When talking about old-style Ryūkyūan martial arts, it should be remembered that neither Japan, nor Satsuma, nor Ryūkyū was cut off from the outside world in terms of intelligence. Quite on the contrary. They were very much aware how from the mid-18th century to 1840 the British East India Company emerged as the world’s largest drug dealer. China under the Qing was unable to stop the import of opium and slithered into the First Opium War (1839–42). Defeated by the modern army of the British Empire with relative ease – artillery in place, an hour of bombardment, infantry charge with bayonets mounted – the decline of the once unlimited Chinese hegemony in Asia was launched, gradually deadening China’s scope to that of an informal colony of Western powers.

The Treaty of Nanking (1842) made Fuzhou one of five Chinese treaty ports completely open to Western merchants and missionaries. You remember that Fuzhou was the place where Ryūkyūan martial arts are said to have come from largely, and that it was the place of call for all Ryūkyūan ships to China. As British captain Belcher termed it, the Ryūkyūans supposed that “as we had punished the Chinese we were masters of the world.”

Lovell Pattern 1839 Infantry Musket, 0.75-calibre with socket bayonet, standard Brtish weapon during the First Opium War. From: Felton, Mark: China Station: The British Military in the Middle Kingdom 1839-1997. Page 105.

Meanwhile, in Japan, it was Takashima Shūhan 高島秋帆 (1798–1866) who, from 1840, following the outbreak of the Opium War in China, appealed to the shōgunate government in Edo to reinforce Japan‘s military capabilities. When Takashima in 1841 had the first Western style gun corps of Japan openly perform, Western-style bayonet fencing was also demonstrated for the first time. Takashima had studied the techniques from the Dutch in Nagasaki, which also points to Japanese translations of written Dutch textbooks, which was standard procedure back then.

Qing China’s decline was further marked by the Taiping Rebellion (1850–1864) and the Second Opium War (1856–1860), which were accompanied by a reorganization of the Qing military. These events, naturally, resulted in a shift of the Japanese and Satsumese perspective towards Western visitors to Ryūkyū, too. Their significance was increased by the fact that many of the Western vessels were straightforward warships manned with big guns and guard under arms, all officers wearing swords, and the marines equipped with bayonet rifles.

Since Hall in 1816 Western ships entered Ryūkyū ever more until the 2nd half of the 19th century. This illustration shows the American squadron under Commodore Perry at Shureimon. Many of these ships were warships and sabers, bayonets, and arms drill an everyday view for the Okinawans.

During all the visits of Western powers since Hall in 1816, military drills at sea and ashore were ubiquitous. During Perry’s visit, the marine and howitzer divisions were usually landed for drilling purposes at the level plains at Tomari, which were normally used to dry salt from saltwater. In May and June 1853, during Perry’s first visit to Okinawa, there had been military drills on every ship and on shore each day after the squadron came in. On the day following the Shuri Castle visit, a full-dress review of auxiliary craft was held in the harbor. “Seventeen boats, fully equipped and armed, and five of them carrying twelve and twenty-four pounders’ were paraded for the Okinawans to see.”

Other notes follow the same tone, such as “Early this morning the marines went ashore under Captain Slack’s order to drill.” Commodore Perry actually had an interest to extend over Ryūkyū “the vivifying influence and protection” of the U.S. government, least some “less scrupulous” nation–he was thinking about France, Russia or Britain–might “slip in and seize upon the advantages which should [have] justly belong[ed]” to the Unites States. While the U.S. government showed no interest in a too tight intricacy with Ryūkyū, general and division exercises of great guns and small arms, with artillery and infantry drills were ordered by the commodore to be carried out with increased diligence, and bayonet-rifles, fixed ammunition, cutlasses, and ball cartridges were paraded on the island.

Bonham Ward Bax (1837-1877), Captain of the British gunboat HMS Dwarf, was in Okinawa in 1872 “saw no guns or soldiers there”, but noted that each time Ryūkyūan officials came on board they would examine the Western ships and guns. You may rest assured that this was was no coincidence.

Admiral Guérin and French marines embark at Tomari in November 1855.

1874, three years following the establishment of the Imperial Japanese Army, François Ducros of the Armée de Terre Française was invited as a “gymnastic instructor” (taisō kyōkan 体操教官 – taisō or gymnastic referred to military drill) to the Toyama Army Academy 陸軍戸山学校, where he first introduced Western style fencing and bayonet practice. The French used the “Fusil Modèle 1866”, better known as the Chassepot rifle, and this was also used in Japan. It weighed 4.635 kilograms and with its Yatagan bayonet it had a length of 1.88 m.

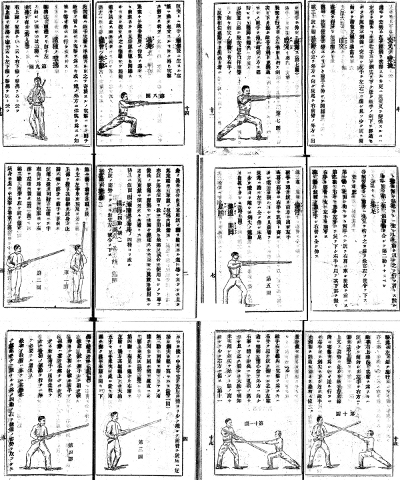

Kenjutsu Kyohan, Part 3 (bayonet fencing), 1889.

At that time, the use of the bayonet in Europe over the last 200 years had changed warfare. Hundreds of Western publications were published in the 19th century alone (see, for instance: Thimm, Carl A.: A Complete Bibliography of the Art of Fence etc., London 1891). In Japan, after Ducros had left the shores of Japan, in 1889 the “Textbook of Fencing” (Kenjutsu Kyohan 剣術教範) was compiled outlining the official Japanese military method of swordsmanship. This textbook was divided into three parts: 1] kenjutsu, 2] guntō-jutsu (saber), and 3] jūkenjutsu (bayonet).

In 1894 the Japanese Imperial Army began to use the straight-edged Type 30 sword bayonet and continued to do so until 1945. It was designed to be used with the Arisaka Type 30 Rifle. Mounted with the bayonet, the Arisaka Type 30 Rifle had a length of 1.680 millimetres and weighed 4.65 kilograms.

Other than the spike bayonet, which was limited to thrusting actions, the above noted sword bayonets allowed slashing and thrusting.

Of course the Western bayonet rifle had an effect on Ryūkyūan Bōjutsu!

To what extent, if any, did the Western bayonet rifle had an effect on Ryūkyūan Bōjutsu?

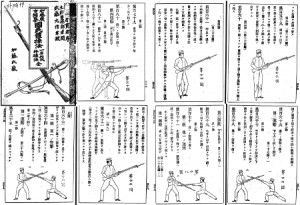

From ” ‘National Gymnastics (国民体操法),’ otherwise known as the ‘Method of Military Drill’ (兵式体操法),” 1896. You can see here that the term “gymnastics” (taisō 体操), which was abundantly used in connection with Karate instruction in Okinawa, was closely related and actually derived from and meant military drill (heishiki taisō 兵式体操).

In Europe, with the advent of the bayonet rifle, the use of all sorts of polearms like the pike and others dramatically vanished. By the early 19th century, the bayonet rifle was standard equipment of all European armies. Hundreds of textbooks were published from early 19th century through to the early 20th century. For fencing, various adaptions were used. One was a small metal disc fitted to the point of a real bayonet. Later systems with spring mounted rods fitted inside the (look-a-like) barrel were used. However, since the early the 19th through to the early 20th century, a “Fechtstange” (fencing staff) was used. According to Constantin Balassa (Fechtmethode, 1844), the “Fechtstange” of course had to have “the length of a rifle together with bayonet.” Their use as a safe tool for practice fights was continued without interruption until the beginning of the 20th century (See, for instance: Turnvorschrift für die k. u. k. Fußtruppen. Kaiserlich-königliche Hof- und Staatsdruckerei, Wien 1903. Abteilung IV. Bajonettfechten. §18. Allgemeine Bestimmungen.)

Now, when in Okinawa in 2009, with permission of Nagamine Takayoshi I recorded an unpublished handwritten book by Nagamine Shōshin. In it is found a page describing the details of an interview of Nagamine with Chinen Masami at the latter’s home. The interview took place on May 14th, 1967, at Shuri Tōbaru town, 2, No. 6, home of Chinen Masami.

In the interview is noted the kata called Yonegawa no Kon 米川の棍. It was created by Masami’s grandfather Chinen Sanrā 知念三良 (1840–1922), the retrospectively designated founder of Yamane-ryū bōjutsu 山根流棒術. Pronounced Yunigwā nu Kun in the Okinawan tongue, the techniques of this kata are mainly performed with the left hand leading. For this reason, it is also called Hidari-bō 左棒, or left-sided Bō. It is a complex choreography and includes a large number of practical techniques. On the left-sided performance of Yonegawa no Kon, it is noted in the interview that:

“The left-sided posture (of Yonegawa no Kon) was Chinen Sanrā’s interpretation of the left-sided posture employed in Jūkenjutsu (bayonet fencing).”

So, according to Chinen Masami, the left-handed Bō-kata called Yonegawa no Kon, which was created by his grandfather, was devised or adapted to the bayonet-rifle fencing of the time, therefore holding the Bō like a bayonet-rifle with the left hand forward. Looking at Chinen Sanrā’s life dates (1840–1922; or otherwise 1842–1925), this completely corresponds to the era of Western visitors to Okinawa, Western bayonet fencing introduced to Japan, and Western bayonet fencing as an indispensable part of infantry tactics.

In 1874, when François Ducros began teaching French style bayonet practice at the Toyama Army Academy, Chinen Sanrā was 34 (32, respectively) years old. In 1889, when bayonet fencing was showcased in part three of the “Textbook of Fencing” (Kenjutsu Kyohan), Chinen was 49 (47, respectively) years old. During this time and afterwards, the Japanese Imperial Army used sword bayonets, which allowed for slashing and thrusting. Yonegawa no Kon includes a lot of strikes, as well as eighteen tsuki, and four nuki-zuki which – if the bayonet theory is correct – refer to strikes with the butt end of the rifle.

Soldiers of the Kumamoto Garrison with bayonet rifles (jūken) in front of the Kankaimon front gate of Shuri Castle. Following the Ryūkyū Shobun, the Kumamoto Garrison had been sent by the Meiji government and was lodged inside Shuri Castle.

A technique found at the very end of Yonegawa no Kon is a backwards jump, which is also found in Western textbooks with the command “Jump – backwards!” as described in Austrian textbook of 1903, the same year when later aikidō founder Morihei Ueshiba enlisted in the 37rd Regiment of the 4th Division in Ōsaka, where, due to his skills with the bayonet he was nicknamed the “King of Soldiers.”

Moreover, Okinawan soldiers like Yabu Kentsū and Hanashiro Chōmo and all served as infantry men in the 1st Sino-Japanese War (1894–95) and the Russo-Japanese War (1904–05). At that time the standard infantry rifle was the Murata rifle, of which there were three models of sword bayonets (Type 13, Type 18, and Type 22), or the Arisaka Type 30 Rifle with a Type 30 sword bayonet. Fencing (gekken 撃剣) performed at various school festicals at the Shuri Middle school and elsewhere since 1905 might have included jūkenjutsu. In July 1909 the Ryūkyū Shinpō reported about jūkenjutsu showcased at the memorial service for soldiers killed in action, and in November the same year about the jūkenjutsu tournament held in Shimajiri District commemorating the imperial rescript.

Detail of the Chassepot Fusil modèle 1866 with bayonet. Photo from: www.deactivated-guns.co.uk

Yonegawa no Kon, therefore, might be said to have been created by Chinen Sanrā around the late 19th or early 20th century. This does not even slightly contradict with the technical contenct of Yonegawa no Kon, nor with the age of Chinen Sanrā, nor with anything else shown above, particularly not with Chinen Masami’s own words, that the left-sided bōjutsu is nothing but Chinen Sanrā’s interpretation of jūkenjutsu (bayonet fencing).

It should be added that in Okinawa, there is an oral tradition relativizing the Western influence. It claims that Yonegawa no Kon originally was performed in a right posture and states:

“Apparently, since a certain time bayonet fencing (jūkenjutsu 銃剣術) spread. Since guns are usually fired from the right shoulder, the left foot and left hand are in the front and the posture of the bayonet rifle in jūkenjutsu is also a left-sided posture. In this way the techniques of Yonegawa no Kon were changed from a right to a left posture, to be used as fighting techniques against the left posture of bayonet fencing.”

While it acknowledges an influence of bayonet fencing on Yonegawa no Kon, it ignores most of the facts established earlier in this article. To begin with, bayonet fencing did not spread simply at a “certain time”, but Bayonet charges were considered most important prior to and especially since the time of Napoleon. In fact, by the first half of the 19th century, it was a standard of infantry all over the world. Bayonets were not only clearly visible in Okinawa since the early 19th century, but also on the Asian continent (Opium War etc.), and only lost their importance after WW I. The fact that Yonegawa no Kon was created by Chinen Sanrā allows for its creation since the late 19th century at earliest, and even the early 20th century at latest.Without any doubt, Chinen Sanrā was active during the “bayonet years.” The official adoption of bayonet fencing in the Japanese Imperial Army since 1874 and the fact that Okinawan soldiers almost exclusively served as infantry men speaks volumes. And all the rest of it. In other words, this relativization of Western influence within Okinawa’s own oral traditions might emphasize its own bona fide self-perception. The idea that Yonegawa no Kon originally existed as a right-sided kata and only later was changed to the left, would first of all require some positive evidence to be taken into account. If no such evidence appears, Yonegawa no Kon can and should be considered to have been an excercise specificly designed for bayonet-related practice.

In any case, below find a video of Yonegawa no Kon. You might now consider the techniques for or against the bayonet rifle. Moreover, bayonet fencing was also devised to function against sword and cavalry.

© 2016 – 2017, Andreas Quast. All rights reserved.