Recently the topic of Taoism in martial arts was raised by quoting Kai Filipiak PhD, stating that while “there is evidence for martial practice in many Buddhist locations […] historical evidence for Daoist practice of martial arts is rare.” (Academic Research into Chinese Martial Arts: Problems and Perspectives, p24.)

Usually Okinawan martial arts people are practically oriented, result-oriented, opportunistic, or lean towards certain personalities and their recent traditions. When it comes to language, but at the latest with the topic of religion, everyone soon hops off. In today’s operation of “Karate” there are various streams, like more or less business-oriented, culture oriented, application oriented etc.pp. Most of them have in common that topics such as Taoism rarely find a place and – after a short, formal phase of respectfulness – are usually simply ignored or a little bit ridiculed. This is something for academics, who – in the minds of practitioners – have no clue anyway.

Knowingly or not, everybody in Okinawan MA circles just loves Itosu’s words “Karate did not develop from Buddhism or Confucianism.” In this case here it is tacitly enlarged by Taoism.

Where things different in Ryūkyū?

The following is by no means meant to be exhaustive.

Already in the second half of the fourteenth century the port city of Naha spontaneously developed into a melting pot of sea merchants plying back and forth the southern sea route between Japan via Ryūkyū to Yuan China. These private groups consisted of Chinese, Japanese, Koreans, and people from South East Asia. Following Ryūkyū’s participation in the Ming’s investiture and tributary trade system, local powers are thought to have further improved its functions and facilities as a port city, with this process continuing through the Ryūkyū kingdom’s government-sponsored entrepôt trade during the so-called Great Age of Trade (Dai Kōeki Jidai 大交易時代) in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. (Uezato 2008: 60, 73-74)

An ancient Omoro song-poetry tells about old Naha, which was originally an islet:

“The Son of Heaven reigning in Shuri had a floating islet remodeled. Ships from China and southern countries gather at this port of Naha.” (Matsuda 1966: 291. Omoro sōshi, Chapter XIII, No. 8.)

The islet was called Ukishima (浮島, floating island), connected to the mainland by a kilometer-long causeway called Chōkōtei (長虹堤) continuing on to the royal capital of Shuri. Ships from China, Southeast Asia, and Japan would come and go and various merchant groups from China, Japan, Korea, and the South Seas had their own living quarters. There were temples and shrines, different villages and foreign settlements, and various agencies for overseas trade. (Uezato 2008: 61-63.)

Naha was divided into the Chinese settlement of Kumemura 久米村 and the districts of Higashi 東 and Nishi 西, Wakasamachi 若狭町, Izumisaki 泉崎, and Tomari. Situated within the port area was the Royal Government Trading Center (Oyamise 親見世), the open area in front of which was used as a marketplace, and vis-à-vis was the Tenshikan (天使舘) where the Chinese investiture envoys stayed. On a small island in the harbor there was the Omono-gusuku 御物城 warehouse, where goods for overseas trade were stored. The center of the island was occupied by the Chinese settlement of Kumemura, surrounded by earthen walls, and it was traversed from northwest to southeast by a street called Kume-ōdōri 久米大通, which was likened to a dragon following feng-shui geomantic thought. To the north of this street stood Tensonbyō 天尊廟, a Taoist shrine complex for the Heavenly Cannons and Statues, and to the south the Upper and Lower Tenpigū 天妃宮, also known as Masobyō 媽祖廟, i.e. Temple of the Taoist deity Mazu. To the north of Kumemura lay Wakasamachi 若狭町, which, according to oral tradition, was founded by Japanese. Here were situated the Nami-no-Ue Kumano Gongen 波上熊野權現, as well as Jizōdō (地蔵堂, temple of the protective Bhodisattva of the pregnant, the children, and the roads) and Ebisudō (夷堂, temple of the deity of good fortune) shrines, furthermore the Kōganji (廣嚴寺) Zen temple with its cemetery for Japanese, and lodgings for maritime people based on the Tokara Islands, and it is thought that there was a marketplace in front of Ebisudō. Wakasamachi was traversed from northeast to southwest by a street called Wakasamachi-ōdōri 若狭町大通, which intersected with Kume-ōdōri, running roughly from north to south. Izumisaki lay across the Kumoji River, opposite the port town of Naha, and, having no key harbor facilities, it is thought to have been a subsidiary settlement that developed as the residential area of Ukishima spreading across to the other side of the river. (Uezato 2008: 62.)

So there were a bunch of Taoist and Buddhist shrines and temples.

Let’s look at Tensonbyō. The Tensonbyō was dedicated to the supreme deity of Chinese popular Taoism, which had been introduced to Okinawa by the thirty-six families of Kume. This supreme deity refers to Guan Yu 關羽 (-219), alias Kantei Ō 關帝王 (chin. Guan Diwang), sworn brother of Liu Bei in the Romance of the Three Kingdoms. Feared fighter known for his loyalty and value concepts. Posthumously honored and identified as the patron bodhisattva Sangharama.

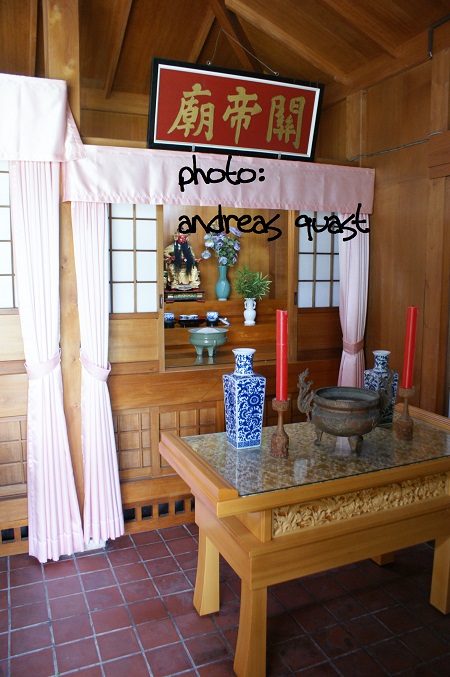

Kantei-o AKA Guan Yu in the Tenson-byo.

Guan Yu was a general of the Shu, perceived as a fearless warrior, known for his virtue and loyalty and who even appeared in the famous historical novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms. His alias, Kantei Ō, literally ‘Monarch of the Frontier Post,’ points to his role as a protective patron who secured the country’s borders.

On the name plaques still found today in the Tensonbyō he is revered as Tenson Kantei (天尊關帝), from which the shrine derived its name. He is also known as the ‘Saint of War’ (wu sheng 武聖, i.e. the deified Guan Yu), which is of complementary to Confucius, who was known as the ‘Saint of Culture’ (wen sheng 文聖). At this point we can actually see that an original concept of wuwen (文武, the civil and the military realms, Jp. bunbu) existed in Ryūkyū since olden times.

Guan Yu was also worshiped as the guardian deity of the king of Ryūkyū (Kantei Ō no Kakejiku ga satogaeri 関帝王の掛軸が里帰り [A hanging scroll of Guan Diwang returning home]. Ryūkyū Shinpō, 1997/6/26), and so it might be considered no coincidence that the Tensonbyō was situated right beside the Gokokuji (護国寺, the Temple for the Protection of the Motherland).

The Tensonbyō is also assumed to have been the repository of the Okinawan Bubishi 武備志, a collection of topics on empty-handed fighting, enhanced by the figure of the Būsaganashi, who was obviously considered important in this tradition and who is of course a Taoist deity. A statue of it was refered by Miyagi Chōjun as the deity of martial arts and is still today found in the Jundōkan dōjō in Naha Azato.

One more point: The first educational facilities (schools) in Ryūkyū were the above mentioned Taoist shrines in Kume. (See Tsūko-ichiran, Ryūkyū-kunibu.) Their successor school – the Meirindō in Kumemura – taught and performed old style Ryūkyūan martial arts, as is exemplified in the 1867 martial arts items during the performances in honor of the Chinese investiture envoys.

So while it might have had no direct influence on martial arts – in sense of specific Taiost practices, like bre athing, gymnastics, use of herbs –, Taoism and its belief systems in Ryūkyū were apparently indeed related to martial arts since early times, yet maybe on a specific (non-physical) level. Things get a bit complicated by the fact of a targeted de-Sinicization after the establishment of Okinawa as a Japanese prefecture in 1879. However, in the end Taoism was a part of the cultural complex of Kumemura, and therefore of the old Ryūkyū kingdom and its martial arts. At least it seems impossible to just shout “Nay!” (= “I am not interested”) without any hints contrary to the above.

athing, gymnastics, use of herbs –, Taoism and its belief systems in Ryūkyū were apparently indeed related to martial arts since early times, yet maybe on a specific (non-physical) level. Things get a bit complicated by the fact of a targeted de-Sinicization after the establishment of Okinawa as a Japanese prefecture in 1879. However, in the end Taoism was a part of the cultural complex of Kumemura, and therefore of the old Ryūkyū kingdom and its martial arts. At least it seems impossible to just shout “Nay!” (= “I am not interested”) without any hints contrary to the above.

So it might be interesting to find out more details. Even if in the end it will turn out that Taoist concepts were merely applied to martial arts.

BTW, you can read more about the floating islet of Naha, Guan Yu, temples and shrines, and of course martial arts in my “Karate 1.0”.

© 2016, Andreas Quast. All rights reserved.