Translator’s note: The Japanese language version of this article published on the Motobu-ryū website has sparked a lot of interest among the international karate and Ryūkyū bugei community. In addition, there was a request for a translation. For this reason I translated it here with the kind permission and support of Motobu Naoki Shihan of the Motobu-ryū and Motobu Udun-dī. As it is a quite difficult topic with some rare terminology, I added a minimum of explanations at the end (terms noted by a preceeding arrow →). Any inadequacy is mine alone.

On the distinction between Shuri-te and Tomari-te

Salt drying field at Tomari. From: Hawks, Francis L.: Narrative of the Expedition of an American Squadron to the China Seas and Japan, performed in the years 1852, 1853, and 1854, under the command of Commodore M. C. Perry etc. 1857 (opposite page 362)

There is a theory that claims that “Motobu Chōki is Tomari-te”. Have you ever wondered where on earth this theory might have come from? The Motobu-ryū does not make such a claim. To begin with, Tomari-te (Tūmaidī) has the meaning of the tī (bujutsu) of the →shizoku of Tomari village (today’s Naha-shi Tomari), and Motobu Chōki came from Shuri Akabira village, which means he was from Shuri →shizoku, and not from Tomari →shizoku. In karate the classification into so-called Shuri-te, Tomari-te, and Naha-te is only a rough regional classification of the bujutsu of the →shizoku who lived in each of these regions, and not a classification according to an exact stylistic or methodical content. This is a matter that Motobu Chōki himself has pointed out in his books.

So looking up various sources, this claim seems to have originated from Nagamine Shōshin (founder of Matsubayashi-ryū). One of his former teachers was Kyan Chōtoku, who in turn was a direct student of Matsumura Sōkon, the restorer of Shuri-te. Another former teacher of his was Motobu Chōki, who in turn was a direct student of Matsumora Kōsaku, the restorer of Tomari-te. In order to perpetuate the martial virtues (butoku) of both Matsumura and Matsumora to future generations, Nagamine used the character “matsu” as found in both persons’ names to call his own style Matsubayashi-ryū.[1]

But would a distinction according to either of the two systems of tradition be accurate?

Kyan Chōtoku was originally from the Kyan →dunchi in Shuri Gibu village and was a genuine member of the Shuri →shizoku. He first studied karate under his father Chōfu, and from the age of 16 years (→kazoe) studied under Matsumura Sōkon for two years. Afterwards, together with his father Chōfu he moved to Tōkyō where he stayed for a total of 9 years as part of the inner circle of →Marquis Shō Tai, the former and last king of the Ryūkyū kingdom. After returning home, he studied Tomari-te with Matsumora Kōsaku and Oyadomari →Pēchin from Tomari village.[2] In addition, Nagamine in his martial resume of Kyan noted that Mr. Kyan in this way not only practiced Shuri-te, but also Tomari-te.[3] So when distinguishing the tradition based on the system it would not be accurate to limit it to the classification of Shuri-te. By the way, Mr. Kyan had been adopted into the Motonaga family, which was a →monchū of the Motobu →Udun. His real name was thus Motonaga Chōtoku. This Motonaga house by way of adoption became a →monchū of the Motobu →udun. From this reason the descendants of Mr. Kyan currently call themselves by the family name of Motonaga.[4]

Motobu Chōki, on the other hand, at the age of 12 years (→kazoe) studied under Itosu Ankō (Shuri-te) who had been invited by the Motobu →udun, and while growing up he studied under Matsumura Sōkon (from Shuri Yamagawa village), Sakuma →Pēchin (from Shuri Gibu village), and Matsumora Kōsaku from Tomari.[5] In addition, from Nagamine’s martial resume of Motobu Chōki[6] can be seen that three of Chōki’s teachers were persons from Shuri, and only Matsumora came from Tomari. It is therefore also inaccurate to limit the classification of Motobu Chōki to Tomari-te.

From the above it becomes clear that Kyan Chōtoku has trained in both Shuri-te and Tomari-te, and the same holds true for Motobu Chōki. In addition, both Kyan and Motobu have studied under both Matsumura Sōkon and Matsumora Kōsaku. And therefore it is apparent, in sense of the above noted systems of tradition, that it is an inaccurate classification to categorize Kyan Chōtoku as Shuri-te and Motobu Chōki as Tomari-te.

Now, when classifying the systems of tradition in this way, yet another issue arises. Namely, there is no clear distinction between the contents of Shuri-te and Tomari-te.

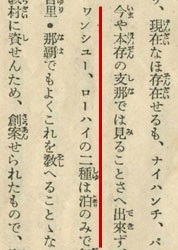

Note on Wanshū and Rōhai (From Motobu Chōki: Watashi no Karate-jutsu, page 4).

As regards Motobu Chōki, the Shuri-te prior to Itosu was tī (Koryū Shuri-te) of the Matsumura and Sakuma period. And the Naha-te prior to Higaonna Kanryō was tī (Koryū Naha-te) from the era of Bushi Nagahama. It should also be noted that Bushi Nagahama in addition also taught Itosu Ankō.

It was stated by Motobu Chōki in his book that Koryū Shuri-te and Koryū Naha-te had differences in contents when compared to their modern successors. However, he made no equivalent statement about Tomari-te. Only mentioning it in one short line, he said that prior to the abolition of the feudal fiefs – in Ryūkyu between 1872 and 1879 -, “The two kinds Wanshū and Rōhai were only practiced in Tomari village”. And these two types of kata were neither practiced nor taught by Motobu Chōki. Or he possibly learned it during his younger years, but in later years did not practice these two Tomari-te-specific kata. The fact that both Wanshū and Rōhai contain neko-ashi-dachi, which Motobu Chōki disliked, essentially underlines the low probability that he had trained in these kata. According to →Motobu Chōsei, Motobu Chōki did not use neko-ashi-dachi at all, even when it was part of a kata.

In addition, he said that the practice methods of Matsumura and Itosu (who was under the influence of Bushi Nagahama of Koryū Naha-te) were different, while he not noted about a difference in the practice methods of Matsumura and Matsumora. It seems that Matsumura Sensei placed emphasis on kumite, which also applies to Matsumora Sensei. In this context: Matsumora Sensei’s teaching style was to issue homework assignments to his skillful students. For example, he would issue a task related to kumite or the like, and without him providing an early solution the disciples had to come by the correct answer by themselves by the time of the next practice meeting. This anecdote appeared in the Karate round-table discussion of 1936.[7] In addition, Matsumura Sensei also advocated the importance of adaptation to the circumstances in the practical application of kata (putting it to practical use in kumite) as well as in real combat (jissen). Therefore the ideological difference between Matsumora and Matsumura is also not considered to have been any significant. Ultimately, besides the personal characteristics of Matsumura and Matsumora, it is appropriate to assume that there was no essential difference between Shuri-te and Tomari-te.

It should be noted that there is the theory of a contest bout having taken place between Matsumura Sensei and Matsumora Sensei, and there is also a theory that supposes Matsumora Sensei has studied under Matsumura Sensei.[8] But it is difficult to support these theories by means of historical source material of that era. However, the possibility of some sort of exchange between the two is perfectly imaginable. By the way, both Matsumura and Matsumora are pronounced “Machimura” in Okinawa dialect. As in Okinawa many episodes about both these persons were and are handed down, there are sometimes cases in which both persons are mistaken for one another. For karate researchers it is necessary to pay attention to this point, too.

In case of Motobu Chōki the problem is not so much a difference between Shuri-te and Tomari-te, but rather the difference between a) Matsumura and Sakuma →Pēchin era Koryū Shuri-te and b) Kindai (modern) Shuri-te since the era of Itosu. In Motobu Chōki’s literary works as well as in the articles about the Karate round-table discussion of 1936,[9] this difference was repeatedly brought to everyone’s attention. This problem awareness was by no means unique to Motobu Chōki. We can also see it from other examples, like from Sai Kahō who said that “Matsumura Sōkon’s Karate was the original real thing; Itosu Ankō’s method was riddled with mistakes”, and furthermore that “After reaching the condition as Okinawa Prefecture (since 1879), the real deal karate disappeared. Lately the karate of the people of Shuri was riddled with mistakes and it is below criticism (not worth criticizing)”.[10] To a certain extent this problem awareness seems to have been the common understanding among those karateka who actually knew the koryū versions of it.

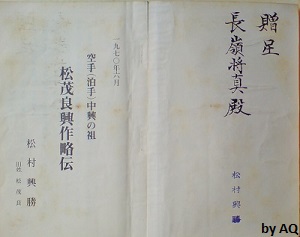

Present of the author Matsumura (former name Matsumora) Kōshō to Nagamine Shoshin: “The Restorer of Karate (Tomari-te) – Biography of Matsumora Kosaku (1970)” (from author’s collection).

Well, generally in karate history the acknowledgment of Matsumora Sensei tends to be low when compared to that of Matsumura Sensei and Itosu Sensei. But this doesn’t mean that he fell behind in his martial art, but simply that he is mentioned less. Under these circumstances it is indeed a wonderful thing that Mr. Nagamine devoted one chapter of his book to describe Matsumora Sensei’s life and to praise his significant accomplishments. And therefore, aside from the pros and cons as regards a distinction between Shuri-te and Tomari-te, the fact that his styles’ name includes one character of Matsumora Sensei’s name in order to convey his martial virtues to later generations, can be considered a precious thing.

End of article

Transl. Notes:

- →Marquis Shō Tai: the rank of marquis (kō 侯) was the second highest amongst five old Japanese aristocratic ranks; it was placed between the duke (kō 公) as the highest and above the count (haku 伯) as the third.

- →Motobu Chōsei: Son of Motobu Chōki, and the inheritor of both Motobu-ryū (his father’s style) and Motobu Udundī (the art of his uncle, Motobu Chōyu).

- →kazoe: i.e, age in which the counting of years follows the traditional Japanese calendar year: at birth a person is counted as already one year old, and at the turn of the year he becomes one year older)

- →monchū: lit. “inside the gates” or “inside the family”; patrilineal groups originally limited to the upper class, although the peasantry had reorganized its society along similar principles by the end of the 18th century.

- →pēchin: Early modern royal government rank.

- →shizoku: Shizoku is a Japanese term meaning “ancestry in a samurai family; the warrior class.” The concept of shizoku was introduced to Ryūkyū by Satsuma, although on the islands no actual warrior class in the Japanese sense existed. That’s why for Ryūkyū it is usually called keimochi, literally “possessing a genealogy”. The keimochi were represented by the Ryūkyū court ranks 1a to 9b. The 1st major to the 4th minor rank constituted the senior keimochi who managed important offices of the government. This was the strata that bore the designation of dunchi. The keimochi of 5th major rank and below correspond to the ordinary keimochi, mainly those with satonushi and chikudun family ancestry and in the ranks 5a-9b. In the colloquial language the keimochi were commonly referred to as yukacchu. There were also keimochi without official posts called muyakushi, and keimochi without official post but working in agriculture, called yadoi.

- →dunchi: Designated the residences as well as the families of the senior keimochi ranks 1a-4b (uēkata and pēkumi). When speaking about these persons as well as their families and family members, they were generally called, for example, Tomigusuku Dunchi, Gima Dunchi etc.

- →udun: Designated the residences as well as the families belonging to royalty (anji-be, omoi-guwa-be), which were all above the rank system of the keimochi. Instead of using their family names, the ōji and anji would generally assume the name of their endowed territory, e.g. Nakijin Ōji, Motobu Anji etc. The term udun was also used as a honorary title or a sobriquet to indicate the whole family of the person, such as Nakijin Udun, Motobu Udun etc. The only exception of an udun family that did not belong to royalty was the Kunigami Udun of the Ba Clan, as the eighth generation Seimi was an adopted child.

Footnotes:

[1] Cf. Okinawa Karate Kobudō Jiten 2008.

[2] according to Kyan Chōtoku: Memories of Karate, 1942

[3] Nagamine 1975: 67-68

[4] As explained on the Motobu-ryū website: Kyan Uēkata Chōfu (Chinese-style name: Shō Ishin, born 1839) was the eldest son of Motonaga Chōyō and a member of the 8th generation of the Motobu →Udun. His grandmother was Manabe, the third daughter of Kyan Uēkata Chōiku. Chōfu had been adopted into the Kyan family at the age of 17, in order to become the head of the Kyan household. He studied karate under Matsumura Sōkon. Chōfu’s third son Chōtoku in turn was adopted back into the Motonaga family in order to continue the succession of his father’s family. Notwithstanding, he continued to use his birth name Kyan until his latter years.

[5] from Motobu Chōki’s biography in his book “Watashi no Karate-jutsu”

[6] Nagamine 1975: 71-75

[7] Ryūkyū Shinpō, November 9-11, 1936

[8] Matsumura Kōshō (previous family name: Matsumura): Karate (Tomari-te) Chūkō no So – Matsumora Kōsaku Ryakuden. 1970, p. 40.

[9] Ryūkyū Shinpō, November 9-11, 1936

[10] This statement was given by Kojō Kafu (born 1909) during an interview by famous martial arts historian Fujiwara Ryōzō. The person Sai Kahō he referred to is Kōjo Kahō (1849 – 1925) of the Sai clan, who was Kafu’s grandfather. He was a →shizoku member from Kume village and 4th generation of the Kōjo-ryū. Nickname “Gakusha-tanmē (the venerable old scholar)”. He studied Confucianism and cultivated karate-dō, bō, and jō. BTW, Kōjo is pronounced Kogusuku in Okinawan dialect. The above cited statement by Kojō Kafu was published in: Gima Shinkin and Fujiwara Ryōzō: Taidan – Kindai Karate-dō no Rekishi wo Kataru. Bēsubōru Magajin-sha, Tōkyō 1986, p. 95.

It should be noted, though, that on p. 96 Kojō Kafu further cited his grandfather Kahō saying “Instead I think Higaonna Kanryō brought back the skill into karate after his return (from China)“. As Higaonna in China also trained at the Kojō dōjō in Fuzhou, Kafu possibly superelevated his own lineage of Kōjo-ryū while diminishing modern Itosu-based Shuri-te. It should be borne in mind that in martial arts research it is sometimes difficult to distinguish between arguments that are based on “style-pride”; thinking in relative terms is necessary. This awareness to relative terms was formulated by Gima Shinkin in his reply to the above issue:

“However, even if it’s close to the truth, when it comes to the evaluation in modern karate history, it becomes necessary to see it at all from a different angle. That is, in this situation it is impossible to insist on a high-handed truth only. In the case of Itosu Ankō Shihan, he created the Heian (Pinan) kata, and in the Naihanchi kata he carried out a process of educational reorganization, which is why he divided it into three levels. If you look at these kata from the perspective of the martial arts of the Sōke of the Ryūkyū era Sai clan, you might reflect on them as being arbitrary kata full of mistakes. However, Itosu Shihan, because he was a creative person active in the transition of the era and considering it as Itosu-ryū, it is not a problem at all.”

Biblio:

1) Matsumura Kōshō (previous family name: Matsumura): Karate (Tomari-te) Chūkō no So – Matsumora Kōsaku Ryakuden. 1970, p. 40.

2) Gima Shinkin and Fujiwara Ryōzō: Taidan – Kindai Karate-dō no Rekishi wo Kataru. Bēsubōru Magajin-sha, Tōkyō 1986, p. 95.

3) Nagamine Shōshin: Shijitsu to Dentō mamoru Okinawa Karate-dō, 1975.

© 2015 – 2018, Andreas Quast. All rights reserved.