In this 4th part of his article on the character and weapons of the Ryūkyū Kingdom, Nakahara discusses the influece of the Shimazu invasion of 1609 and the theories of a peaceful and weaponless kingdom of Ryūkyū since the time of King Shō Shin. Of particular interest is that in both Okinawan and Western karate circles the unfounded idea of a peaceful and weaponless kingdom gained much popularity and served as a theory of origin of an

- a) indigenous,

- b) unarmed martial arts that is

- c) older than the import of Chinese kenpō and

- d) whose techniques have been handed down over hundreds of years.

While leading the reader through the various historical stages, Nakahara comes to an incredibly coherent and interesting conclusion: The peaceful condition and auspicious society reached by the Ryūkyū Kingdom following 1609 was due to the military power of the Shimazu House. This was understood and supported by leading Ryūkyūan politicians and part of their political agenda.

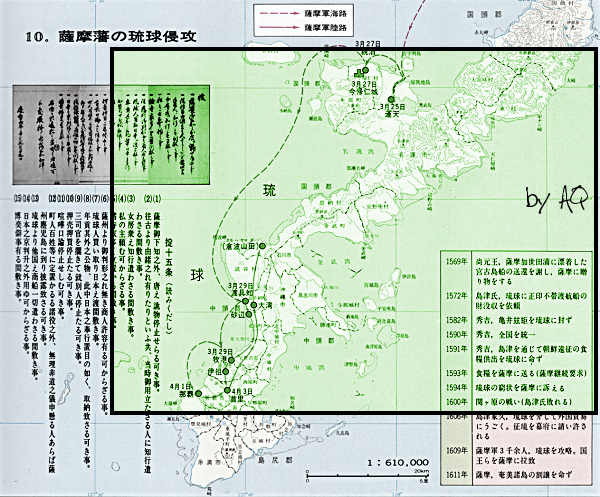

Details and route of the Shimazu invasion of 1609. Miyagi Eishō/Takamiya Hiroe 1983: 53.

This perspective might shake the particular portion among karateka who believe karate was born in the indomitable character of those untainted, suppressed, yet historically ever peaceful Okinawans. Another portion, those who strongly emphasize a picture of a secret Ryūkyūan warrior of old, who possessed world-class skills despite the fact living on a small island with a limited opportunity for actual comparison, might be glad they don’t have to worry about all the philosophical yadda yadda. And the hipster and sportster among us don’t care anyway.

However, again drawing on already established historical conclusions: as Gutzlaff noted following his visit in August 1832, the Ryūkyūans are “however, by no means those simple and innocent beings which we might at first suppose them to be.”

Special attention should also be given to Nakahara’s observation that the karate circles, “by lumping everything together” often draw their own conclusions to establish a subjectively coherent picture. In the present case, the theory formulated by the karate circles, though untenable, has survived a whole century.

Be it the representants and defenders of the “indomitable”-, the “warrior”-, or the “sportster”- and “hipster”- faction: non of these attitudes hitherto provide a satisfactory definition of historical karate beyond personal preferences, but instead are really modern and lopsided approaches. Digging and adjusting shall continue.

Nakahara Zenshu: Character and Weapons of the Ryukyu Kingdom (4)

The illustration shows Oda Nobunaga and Akechi Mitsuhide pounding the rice, Toyotomi Hideyoshi kneading the dough, and Tokugawa Ieyasu eating the rice cake (mochi). It is an allegory to the unification of Japan by Oda, Toyotomi, and Tokugawa, also known as the Three Unifiers of Japan (san’eiketsu 三英傑). Papinot, E.: Dictionnaire d’Histoire et de Géographie du Japon. 1906. P. 783

About one century after the era of King Shō Shin, the house of Shimazu invaded Ryūkyū. Following the rivalry of local warlords during the so-called Warring States Period of Japanese history (approx. 1467-1568), and following the passing Oda Nobunaga (†1582) and Toyotomi Hideyoshi (†1598), Japan entered a period of stability due to the leadership of the Tokugawa family under Tokugawa Ieyasu (*1543; †1616). The Shimazu themselves surrendered to Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s invading army, and furthermore took a flight from Sekigahara in 1600 and kowtowed to Tokugawa Ieyasu. With the surviving political power limited to their home province, their overall strength at the time is debatable.

Their strength in the defeat of Okinawa was unequal, too. The ratio of population and productivity was 7 to 1, that of war potential perhaps 100 to 1, or even higher. They also won by means of new arms called teppō (rifles).

Organization of the Ryūkyūan defense system called Hiki. Although Ryūkyū was a quite militaristic kingdom, in 1609 it was no match for the battle-hardened Shimazu warriors. Uezato 2009: 35.

Nevertheless, with the battles inside Kyūshū during the warring states period, the resistance against Hideyoshi’s troops, the Korea campaign, and the Sekigahara campaign, they were definitely experienced. Viewed from their perspective, “(attacking) the small island of Ryūkyū like one bullet, both heaven and people turned to one, and the conquest was no difficulty“. Supreme commander Kabayama, second in command Hirata as well as the rank and file below them have been expert soldier veterans schooled by adversity in many battles. This opposes the theory of Ryūkyū’s factual defeat having been the result of King Shō Shin weapons confiscation, and moreover, the main military force in this war were constituted by the teppō.

Well, the theory of the origin of Karate as a measure of self-defence as a consequence of the confiscation of Ryūkyūan weaponry by the house of Shimazu mainly comes from karate people. By lumping everything together, Shō Shin is said to have abandoned weapons because he was a musician, as a result of which the government became one of culture, of etiquette, and of esteem for music.

Nevertheless, although King Shō Shin proactively seized weapons, he by no means renounced them. And the confiscation of the Okinawan weapons by the house of Shimazu was not reality, as has been previously discussed and approved.

The two issues actually implemented by the Shimazu were the

“prohibition of the possession of teppō”

and the

“prohibition of export of weapons”.

Concerning the former, to the prohibition of teppō had been added the proviso

“However, equipment belonging to the personal property of princes, Sanshikan, and Samurai, are exempted from that rule.”

The first Europeans at Tanegashima in 1542, introducing the first guns which came tob e the prototype for the Japanese teppō. Papinot 1906: 756.

This was officially announced in 1613, that is, four years following the Satsuma invasion. Even if its objective conceivably was the maintenance of public order and security, the definite motive is unknown.

Next, in 1639 appeared a

“memorandum to Ryūkyū, prohibiting the export of weapons.”

To this, a proviso was attached:

“In Ryūkyū there exists the possession of Katana and Wakizashi, and their unhindered sharpening and manufacturing.”

In reality this meant nothing but a new regulation prohibiting the export of teppō and cut and thrust weapons, and has nothing to do with the ownership or confiscation of weapons.

In 1635 the Tokugawa shōgunate government prohibited the overseas export of weapons for all Japan. As a result of this, 4 years later the Shimazu banned “crossing the sea to Ryūkyū” [i.e. exporting weapons to Ryūkyū]. This prohibition of the export of weapons secured the predominance of Shimazu’s armed might towards Ryūkyū, as is shown in Yamamoto Hirofumi’s work Kinsei Okinawa-shi no Moro-mondai (In: Ryūkyū-shi Hyōron, No. 83). It seems not to be very popular to think about this, is it?

Originally, Japan was a country that supplied weapons to China and among the articles carried on Ryūkyū tribute ships to China as gifts as well as among the presents for the investiture envoys (sappōshi) coming to Okinawa, above all else long swords (tachi) were important goods. As an outcome of the above mentioned prohibition it was an important issue to return to the old tradition of the export of weapons [because it allowed a monopoly business for both the house of Shimazu and the Ryūkyū Kingdom].

The Shimazu house

“at all such times received the shōgunate government’s (bakufu) permission, and (although) particularly pleasing to the eye, in Satsuma mainly imitations were produced; swords and spears were produced from pure iron without adding steel to it, and armor was not forged, but made from leather.“

- Translator’s note: The Shimazu house needed authorization by the shōgunate government (bakufu) in Edo for each export of weapons to Ryūkyū, including weapons meant as gifts or for tribute-trade purposes to China.

When the Chinese investiture envoys (sappōshi) for King Shō Tai arrived in Ryūkyū in 1866, chief- and vice-envoy as well as the people below them added up to a group of four hundred and thirty-four persons. At each official ceremony and banquets, the chief- and vice-envoy would receive 2 swords (tachi) each, so it added to 4 swords at each ceremony and banquet. The other persons would receive the value of a sword in silver coins, along with other presents. Even though it is said that these gifts to the envoys amounted to a total 40 swords, these were blunt swords.

In his Hitori-monogatari, Sai On (*1682; †1761, the leading politician at his time) wrote,

“This place [Ryūkyū] is a very peaceful country, where military arts are completely unnecessary, but every year we fear to encounter pirates during our maritime journeys to China. Because of the possible loss [of life, weapons, gifts, and merchandise], it is desirable to get all [Okinawan] samurai instructed in the spear, halberd, and bow and arrow. If there is no objection [by the house of Shimazu], training in firearmes (teppō) is also intended: at least three days prior to the maritime journey to China, practice in firearmes (teppō) should be carried out.”

Sai On himself approved that the armed might of Satsuma was the reason behind the peace in Ryūkyū:

“Anciently, the government of this country had been divided, and repeatedly revolutions occurred. But since reaching the condition under the rule of Satsuma… this country [of Ryūkyū] became an auspicious society.”

Perhaps, rather than this statement having been mere propaganda towards [the house of Shimazu] of Satsuma, this was Sai On’s real intention.

Satsumese and Japanese Martial arts entered Ryukyu via the resident commisioners bureau (zaiban bugyo) in Naha since its establishment in the early 17th century. Photo: Entry on the house of Shimazu in Papinot 1906: 665.

© 2015 – 2022, Andreas Quast. All rights reserved.