ver read one of the articles and studies as regards various facts related to health among aging Karate people? The buzz word making the rounds is “longevity”.

ver read one of the articles and studies as regards various facts related to health among aging Karate people? The buzz word making the rounds is “longevity”.

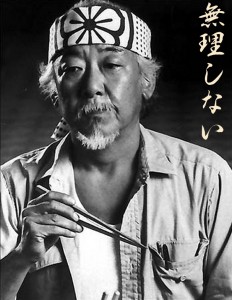

“Don’t overdo”, says Mr. Miyagi. Among others.

Since the 1980s Nakamoto Masahiro pointed out examples of Karate people from the social group of Shuri-te exponents who would reach old ages. The topic is often brought into connection with food: the Okinawan wonder-cucumber called Gōyā (Momordica charantia) is but one of those lifestyle ingrediences Karate people crave for. A study serving the popular Zeitgeist of longevity and exceeding the boundaries of Karate is “The Okinawa Program” on example of how “the World’s Longest-Lived People Achieve Everlasting Health–And How You Can Too”. Of course, it includes a reference to Karate.

All approaches are very positive, with few exceptions, like the only book that dares pointing out negative implications of inflammation on health among aging Karate people.

Martin Meyer, 46, a professor at the Psychological Institute for Learning and Plasticity of healthy aging at the University of Zurich, speaks of the “glorification of aging”: Pretending that aging is a great challenge that simply has to be accepted with pleasure perhaps applies to a minority, but not to the majority of the population. On the other hand, all these approaches to the “glorification of aging in Karate” may be valid, helpful, and have truth in it to a certain degree.

In any case: Add good food, lots of sleep, a well-balanced work-life balance and some fun and it will have a positive impact on anyone’s health (Note: this is legally without engagement).

“The idea is to die young as late as possible.” Ashley Montagu

But seriously now:

What about the relation of physical and mental fitness when aging? Can we borrow statistical data from a field that is better researched than that of the fringe group of old Karate people?

Of course we can:

Karate people are like all other humans, though populism doesn’t want us to agree. (I hear you: “Take that: we don’t care!”.)

Below is a summary of an interview with professor Martin Meyer, 46.

It is written in general language so the medical laymen can understand it, too (always do your target group analysis!). It is not only interesting but leads to a recommendation for setting ones training intensity.

So here it goes:

As regards age-related degration, Meyer explains that it is a fact that the brains of healthy people from age 60 onwards partly show considerable signs of degradation of brain matter as well as other degenerative signs. This is simply part of the normal aging process. On the other hand, in their studies Meyer and his colleagues encoutered numerous older people who show a remarkable cognitive performance.

Good to have: cognitive reserve

This is explained by the fact that the brain is not a static entity, but changes and remodels itself until old age in order to counteract an impending degradation of performance abilities. That is, there is a cognitive reserve or buffer which preserves our mental capacities even longer. This cognitive reserve works because the human brain is not a computer, but a neural network. It is comparable to the railroad system of any larger city: There are heavily trafficked main routes, slow secondary tracks, and some connecting hubs. These are the nodal points in our brains. There, information is being distributed. With increasing age however, some of these nodal points of information distribution begin to dissolve. Therefore, information must seek other “tracks”. It then may take longer to reach your destination.

What is needed in this situation is more patience. In particular, more serenity and less hysteria. We are people, not machines that can simply be repaired by installing a spare part. We react psychologically. We realize that something is not working anymore and feel anxiety, which then often acts as an additional chock block. If I can’t remember a phone number, I shouldn‘t make an “act of state” of it, but accept it and just write the number down on a piece of paper.

Thing is: There is no general rule for the cognitive reserve. Within an age group the gap opens wider with advancing age. Some will already withdraw into mental retirement in their mid-50s, and these you cannot “retrieve” anymore. Others start blooming at age 65 and earn a doctorate or learn a new language.

What you can do

At this point, the importance of motivation, curiosity and personal identification with a profession – or Karate for that matter – can not be stressed enough. In studies about healthy aging, Meyer and his colleagues encountered an 80-year-old, who in his pace of information processing – i.e. a classical indicator of cognitive aging – did much better than some of their Master students. As a reason for this the 80-year-old stated that learning and new things still fascinated him. In other words: Motivation and a higher self-esteem can have a direct positive effect on cognitive performance and thus contribute to the fitness of the brain in old age.

Oh, so you’re a Sudoku god?

As regards the benefits of brain training, Meyer says it is understood by now that commercial brain jogging programs always only improve specific cognitive capabilities: If you train solving Sudoku riddles, you become better at solving Sudoku riddles – nothing more. The practice of brain training does not transfer to other cognitive abilities such as memory performance, problem-solving skills, or logical thinking. The recommendation is simple: It is much better to time and again face new situations and challenges. Life is the best training!

Experience counts – in general terms

As regards the benefits of elders from experience: It is there. Many activities in everyday professional life require strength of concentration and will and the ability, to draw abstract conclusions from existing facts for a rational and objective decision making. However, all this does not necessarily correspond to the strengths of the brain, which in its judgments is often guided by feelings, subjective interpretations, and individual experiences.

In any case: Seniors benefit from their professional experience, because their brains can draw parallels and comparisons to similar situations in the past.

So what significance does physical exercise have for healthy aging?

For one, the brain needs oxygen and nutrients, so it is reliant on a good circulatory system. Studies show that training has an impact on cognitive health in old age. The best prophylaxis in the case of aging is a physical activity at a moderate level, for example: Nordic walking, cycling or dancing. In short: Everything that is good for the heart is also good for the brain. However, we are all slaves of our genes. If I have a predisposition to neurodegenerative diseases, training will help very little. Then I’ll probably be physically completely fit by mid 70s, but demented.

So while it is advantegous to train both body and mind, there’s no guarantee. Live with it. And do both.

One of the Dōjōkun I remember from my Gōjū-ryū school was quite simple:

“Don’t overdo.”

And this seems to be true when getting older with Karate.

© 2015, Andreas Quast. All rights reserved.