he elementary school teacher, Karate man and author Funakoshi Gichin in 1914 noted on rural dances called Mēkata 舞方: He considered these to be not-yet-developed precursors of Karate. Currently these Mēkata are again variously perceived as archetypes of an indigenous “Tī” or a primordial form of Karate, transformed into martial arts dances by a systematic culmination of several primitive martial arts, and handed down within the royal government and in rural “warrior class” villages (yadori).

he elementary school teacher, Karate man and author Funakoshi Gichin in 1914 noted on rural dances called Mēkata 舞方: He considered these to be not-yet-developed precursors of Karate. Currently these Mēkata are again variously perceived as archetypes of an indigenous “Tī” or a primordial form of Karate, transformed into martial arts dances by a systematic culmination of several primitive martial arts, and handed down within the royal government and in rural “warrior class” villages (yadori).

In his essay on the origin of Karate, Iha Fuyū noted that the mutual dances of two or more persons called Aimai, in which the opponents seek to overturn or to defeat each other, originated in the Mēkata. Accordning to Iha, this sort of martial dance was still carried out in various rural areas in the time prior to the War in the Pacific, and were called Sāsā-dī, common mostly in central and southern Okinawa.

These Mēkata were closely related to the so-called Ashibī, a form of entertainment originally performed in gratitude to the gods related to harvests and the like, which developed into various kinds of festivals. Ashibī generally refers to enjoying singing and dancing to music, or the skillful performance of songs, shamisen, and theater plays. There are many terms relating to this, including Mura-shibai, i.e. village or amateur theater. The story surrounding lord Amawari of Katsuren castle was one such popular play. Called Chōja nu Ufushu it was performed in the form of village dances.

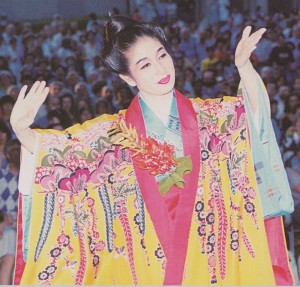

Ms. Masako Ganiku 1993 in Zürich, Switzerland (Okinawa Culture Association 1998)

Furthermore, the Mēkata were part of so-called Mō-Ashibī, which refers to young men and women enjoying time in the fields during night time in rural areas. Mō has the meaning of the Japanese word Nohara, i.e. a rural field. Ashibī comes from Asobu 遊ぶ, i.e. to play; to enjoy oneself; to have a good time. According to this explanation, the Mēkata are perceived as something of characteristic Ryūkyūan provenience. Although performances of Mēkata by old experts are reported until the 1970s, this sort of entertainment died out afterwards and are now considered a so-called “lost transmission of traditional arts & culture.”

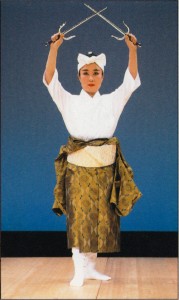

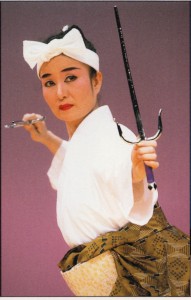

Bu no Mai (from: Okinawa. Traditional Dance, Music & Culture. Okinawa Culture Association 1993)

More recently, contemporary Okinawan Karate authorities, acting on the suggestions made by Funakoshi and Iha in the early twentieth century as described earlier, explained that both Karate and Mēkata have a descriptive technical expression in common, called Tī chikayun. This simply translates as “to use the hands,” which is an integral part of dancing, isn’t it?

Using the simile of the character for hand in the meaning of the martial art called Tī, however, in martial arts circles it had been interpreted as “the skillful use of the martial arts called Tī.” Based on this symptomatic premise the theory was created that the Mēkata were traditions of ancient martial techniques and an original form of a likewise ancient and bare handed martial art of Tī.

In this way, the Mēkata became considered martial arts dances, habitually performed accompanied by the Sanshin on such occasions as the Mō-asibi, Eisā, tug-of-war, bullfighting tournaments etc., in short, at all sorts of festivals and celebrations. It is said that – these following are actual quotes from written material – dancers “competed in battle,” that it contained “actual combat,” or that “challengers danced as fiercely as if clashing and blocking swords.” Occasionally excitement would involuntarily become emotional, and if not mediated, real fights would also occur. In this way this theory describes the Mēkata both as a historical form of actual fighting as well as an art form, which through the centuries coalesced into martial arts dances.

Bu no Mai (from: Okinawa. Traditional Dance, Music & Culture. Okinawa Culture Association 1993)

It should be noted that, as a peculiarity, the Mēkata did not have had fixed forms but were basically improvised dances expressing individual skills and feelings. This is in contrast to the more recently developed dances called Bu no Mai 武の舞, a term only borrowed from actual history which must not be confused with the Mēkata. The current Bu no Mai are choreographies created by teachers of the Ryūkyū dance or by martial artists, and performed on stage following fixed forms, often using the modern Kata of Karate and Kobudō embedded in historical stage settings. These Bu no Mai are modern creations, motivated by the idea of merging the extinct Mēkata and other theatrical performances with the face of Karate and Kobudō.

The Bu no Mai today is a standard repertoire of Okinawan dance. In the style of the Young Men’s Dances (Nise Odori), the dancer wears a white headband, striped gaiters, and the upper half of the kimono tucked in and tied firmly around the waist.

© 2013 – 2015, Andreas Quast. All rights reserved.