Okinawa karate and kobudō is an amazing realm of sport, fitness, self-protection, and culture. It can be many different things for many different people. Embedded within the Okinawa karate kobudō landscape with its emblems, dōjō, photos, certificates, costumes, world championships and the like, there is little reason to question the authenticity and the veracity of it all. In fact, most people just want to be part of the narrative and to affirm it. There is also often the reference to official commendations and honors. I remember stumbling over a big hardcover book of recipients of imperial orders while researching in the late Nagamine Shōshin’s study. Nagamine was listed in there himself. And there was also the framed order with certificate hanging in the dōjō. The family of James Pankiewicz’s wife was a royal supplier, providing sweets for the court.

There are also many references to the Imperial family in Matayoshi Kobudō. For instance, there is an early description of how Matayoshi Shinkō returned to Okinawa temporarily:

“During that time, when [Matayoshi Shinkō] temporarily returned to Okinawa, there was a celebratory martial arts demonstration in Tōkyō in 1915 in commemoration of the [Taishō] Emperor’s accession to the throne, where karate was performed by Funakoshi Gichin, and the ancient martial arts of tounkuwā-jutsu and kama-jutsu were performed by venerable Matayoshi [Shinkō]. (Uechi 1977, information provided by Matayoshi Shinpō)

However, there is no actual record of Funakoshi Gichin performing on this occasion in 1915. There is also no documentation presented as a proof for Matayoshi Shinkō’s participation.

Furthermore, various other events are claimed, such as that Matayoshi Shinkō demonstrated martial arts together with Funakoshi Gichin in 1916 at the Butokuden in Kyōto. (OKKJ 2008:517) While Miyagi Tokumasa (1982) mentions Funakoshi Gichin performing martial arts at the Butokuden in Kyōto in 1916, Funakoshi himself never mentioned that. Moreover, again there is no documentation to prove Matayoshi Shinkō’s participation.

Another example is the following:

“In 1921, when the present emperor [Hirohito], who was the crown prince at the time, visited Okinawa, a martial arts demonstration of karate and kobujutsu was held as part of the celebratory event, in which Miyagi Chōjun performed Gōjū-ryū and venerable Matayoshi [Shinkō] performed kobudō.” (Uechi 1977, information provided by Matayoshi Shinpō)

Again, there is no record of Miyagi Sensei performing on this occasion in 1921, and again there is also no documentation of Matayoshi Shinkō’s participation.

Since then, numerous publications have used and expanded upon these claims. For instance, it is claimed that Matayoshi Shinkō performed tunkwā and kama at the Imperial Enthronement Ceremony of the Shōwa Emperor in Tōkyō in 1928 (OKKJ 2008:517), again together with Funakoshi Gichin, who performed karate (Matayoshi 1997).

In short, there are all sorts of hitherto undocumented claims.

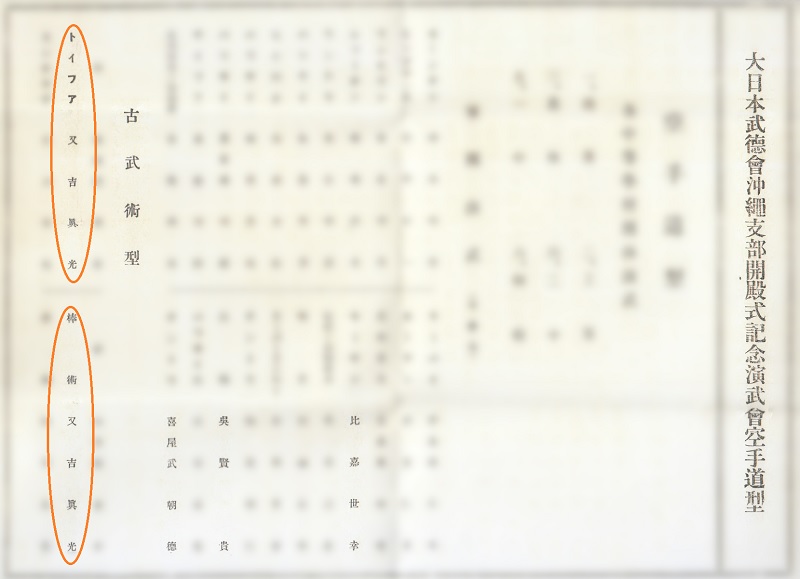

It is for exactly this reason that the following fact is of utmost importance: Over the past half century, not a single publication mentioned the martial arts performance of Matayoshi Shinkō in 1939, presenting toifa and bōjutsu. This demonstration was the Commemorative Demonstration held during the Opening Ceremony of the Okinawa District Committee of the Dai Nippon Butokukai, which took place at the Butokuden in Naha. It was only in 2019 that the printed program of this demonstration became known (see here). It shows the place, date, participants, and martial arts presented at this performance. This means that neither Matayoshi Shinpō nor anyone else in the field of Matayoshi kobudō was even aware that Matayoshi Shinkō had taken part in it. Moreover, several persons related to the martial arts claimed by Matayoshi Kobudō participated in the demonstration, including Kyan Chōtoku, Go Kenki, and others. It might therefore be no surprise that information shared by Matayoshi Shinpō is a little ambiguous around that time, as seen in his self-provided martial record:

Martial Record

1930: Studied under Kyan Chōtoku (karate training) (8 years old)

1934: Studied under Matayoshi Shinkō (biological father) (kobudō training) (12 years old)

1935: Studied under Go Kenki (Chinese Shaolin Crane Boxing) (Age 13)

1945–1960: Instructed Okinawan kobudō in Kawasaki City, Kanagawa Prefecture.

…

There is a gap of 10 years, from 1935 to 1945. Usually, this is understood as a sign that Matayoshi Kobudō kept training for all these years. With the new source, however, it is possible that Matayoshi Shinpō had already left Okinawa by 1939 at the latest, which greatly reduces the time of his possible training under his father.

I interpret the above as follows: The 1939 demonstration was related to the Dai Nippon Butokukai, the Butokuden, and by that indirectly to Imperial Japan. Obviously, as is evident in the complete absence of any written reference, neither Matayoshi Shinpō nor anyone else had any knowledge about the 1939 demonstration. Maybe, after Matayoshi Shinpō’s return to Okinawa around 1960, he heard rumors, inaccurate or ambiguous oral fragments by seniors such as Higa Seikō or others. Maybe it was also a taboo topic, since the Dai Nippon Butokukai was directly linked to Imperial Japanese militarism and ideology, so Okinawans might have wanted to forget about this episode altogether. Maybe it was just bad communication. Whatever the real reason was, Matayoshi Shinpō and his followers creatively reinterpreted their fragmentary knowledge since around 1960, confusing the Naha Butokuden with the Kyōto Butokuden, confusing the Dai Nippon Butokukai with some Imperial Ceremony, then confusing the year 1939 with various other event years, and so finally and cumulatively came up with a whole new history during the prewar era in which Matayoshi Shinkō allegedly took part in.

This might also be one of the several reasons why the Karate Promotion Division of the Okinawa Prefectural Government around 2020 refused to accept the 1939 demonstration program when it was offered to them by the owner, Mr. Satō. It is simple: Because modern Okinawa karate and kobudō’s self-written histories are full of flaws and errors, the protection of old traditions and stories is a major concern. On the other hand, the 1939 demonstration program allows to rectify several fabulist testimonies and historical revisionism created during the postwar era. Fortunately, the owner was able to donate the program to the Okinawa Prefectural Museum, which evaluated the material as “precious items” and accepted to take them in and preserve them for later generations. In the end, Matayoshi Shinkō’s 1939 demonstration should be a matter of huge pride for Matayoshi Kobudō practitioners. However, because it raises doubts whether Matayoshi Shinpō actually has learned from him, and if so, what exactly, this poses a huge problem for this school’s historiography.

Another dimension are the unproven stories of Matayoshi Shinkō demonstrating together with two of the most important prewar karate persons, Funakoshi Gichin and Miyagi Chōjun, in front of an Imperial Prince or even the Emperor. These stories can be interpreted as retrospective attempts to place Matayoshi Shinkō on one level with, and equal to Funakoshi and Miyagi. In short, the stories serve the purpose of creating the myth of Matayoshi Shinkō as the best martial artist in pre-1945 Okinawa. It can also be considered Matayoshi Shinpō’s self-recommendation and appeal to the new, postwar Dai Nippon Butokukai by establishing a long family history of relations to the Dai Nippon Butokukai and the Imperial Family through his father Shinkō.

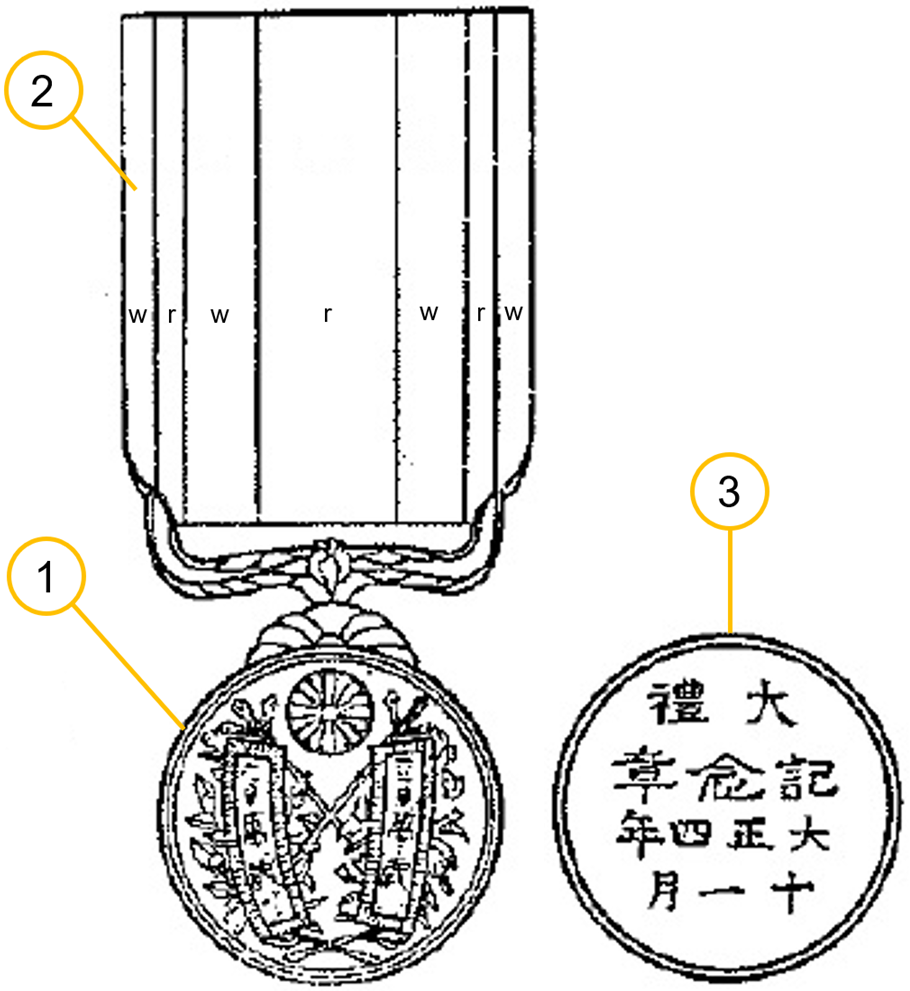

Within the same song of praise can be positioned the claim that Matayoshi Shinkō’s performing skills were amazing to the extent that he was invited (!!!) three times to demonstrate in front of the Japanese Imperial Family. This is said to have happened for the first time in 1917 (sic!), during “one of the most important events in the history of martial arts.” As the hero story goes, Matayoshi Shinkō was invited together with Funakoshi Gichin to demonstrate at the martial arts festival of the Dai Nippon Butokukai at the Butokuden in Kyōto. The adulation continues for another page and finishes by claiming that Matayoshi Shinkō received an “imperial medal” for his “incredible performance skills,” as a proof which is presented the photo of a medal, captioned “Shinko’s 1917 Demonstration medal.”

Now, after seeing a photo of the medal, me and number of colleagues were intrigued to find out more. It took us two minutes to identify and locate the medal. The following is its story.

The Commemorative Medal of the Imperial Enthronement Ceremony of 1915

In 1912, Emperor Taishō assumed the throne upon the death of his father, Emperor Meiji. The enthronement ceremonies were held only three year later, in 1915. August 1915 saw the publication of the Matters of Enactment of the Commemorative Medal of the Imperial Enthronement Ceremony (Imperial Edict No. 154 of August 12, 1915). This is the medal allegedly presented to Matayoshi Shinkō in 1917.

The imperial edict of the time is as follows:

——————————————————————————————–

Matters of Enactment of the Commemorative Medal of the Imperial Enthronement Ceremony (Imperial Edict No. 154 of August 12, 1915)

Article 1: Set up a commemorative medal to commemorate the Imperial Enthronement Ceremony.

Article 2: The commemorative medal as shown on the left.

Medal: Silver, circular form, with a diameter of 3.03 cm. Inside the contour line of the front side is the golden Imperial chrysanthemum emblem in the upper part. On both sides are images of [crossed] cherry tree and tachibana orange branches, overlapped by Banzai banners. On the back side are written the characters “Commemorative Medal of the Imperial Enthronement Ceremony, November 1914.”

Ring: Silver, bay form

Ribbon: The fabric is 3.6 cm in width (1 sun, 2 bun). The color scheme is red in the center, white on the left and right, and with red and white lines on both edges.

The commemorative medal is worn on the left chest with a ribbon.

Article 3: The commemorative medal will be awarded to those listed in the following.

- Those who are summoned to the Ceremony of Accession to the Throne (senso 践祚).

- Those who are invited to the Enthronement Ceremony (sokuirei 即位礼) and to the First Ceremonial Offering of Rice by Newly-enthroned Emperor (daijōsai 大嘗祭).

- Those who were granted banquets at each location in the country.

- Persons involved in affairs related to the Imperial Enthronement Ceremony (tairei 大礼) and other duties associated with the Imperial Enthronement Ceremony.

Article 4: The commemorative emblem may be worn only by the recipient himself/herself for the rest of his/her life but may be preserved by his or her descendants.

Article 5: If a recipient who has been awarded a commemorative medal dies before the award, the medal shall be delivered to and preserved by his or her heir, or the head of the household.

Illustration of the Commemorative Medal of the Imperial Enthronement Ceremony

On ribbon, w = white, r = red.

——————————————————————————————–

Is it possible that Matayoshi Shinkō received this medal? It is, in theory, if he was a member of the groups defined in Article 3 Imperial of Edict No. 154.

First of all, the edict (or any related source) does not mention performers at the Butokuden in Kyōto.

Next, as Article 3-1, the “Imperial Enthronement Ceremony” of Emperor Taishō took place 10-15 November 1915 at the Hall for State Ceremonies (shishiden) of Kyōto Imperial Palace. I cannot imagine that Matayoshi Shinkō was invited to it. As regards Article 3-2, I can not imagine him to be invited to “the Enthronement Ceremony and to the First Ceremonial Offering of Rice by Newly-enthroned Emperor. As regards Article 3-4, I cannot imagine him having been involved in affairs related to the Imperial Enthronement Ceremony and other duties associated with the Imperial Enthronement Ceremony.”

As regards Article 3-3 and “Those who were granted official banquets at each place in the country,” I could imagine Matayoshi Shinkō perform at some local festival or maybe a shrine. These local banquets were held throughout Japan to celebrate Emperor Taishō’s enthronement, taking place at Shintō Shrines in sense of “presenting food to the gods,” or at the Prefectural Office. As an example, at the time of Emperor Shōwa’s enthronement, the list of people invited to these local banquets were high officials such as the prefectural governor, aristocrats, temple and shrine priests, local councilors, and city mayors etc., judges, police chiefs, school superintendents.

Frankly speaking, until documentation to the contrary is provided (which never happens in Okinawa), it is completely unlikely – in fact, completely implausible – that Matayoshi Shinkō received this medal for performing tounkuwā-jutsu and kama-jutsu at the Butokuden in Kyōto in 1917, or 1916, or in Tōkyō in 1915, or whatever someone wrote somewhere.

Rather, it should have become clear already that Okinawa karate and kobudō’s “postwar historiography” sometimes started from rumors and inaccurate or ambiguous oral fragments, and coupled with bad communication it confused various persons, events, places, and dates, and while protecting any and each of the old traditions and stories, it cumulatively applied “the art of creative reinterpretation” to establish the modern heroic narrative of past masters. While Matayoshi Kobudō is a great sport and martial art, the medal might serve as a reminder for this.

A typical recipient of such a medal would be Hamaguchi Osachi. Hamaguchi was a Japanese bureaucrat of the Ministry of Finance and politician. He was in the 2nd Major Rank, and Receiver of the Order of Merit 1st Class. He served as the 25th Minister of Finance, the 43rd Minister of Home Affairs, the 27th Prime Minister, and president of the Constitutional Democratic Party. He was called the “Lion Chancellor” because of his looks.

PS: Bibliographic information not approved for public release.

© 2023, Andreas Quast. All rights reserved.