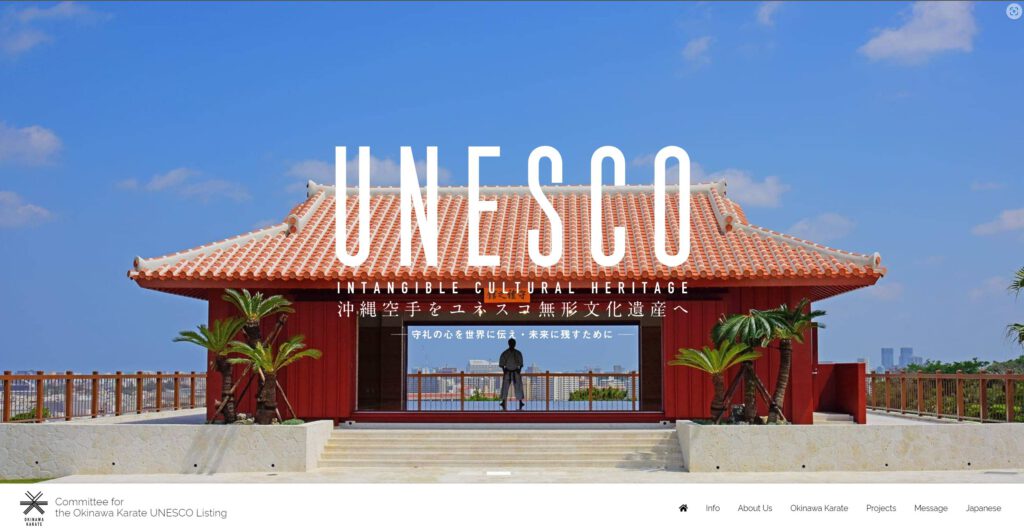

For Okinawa karate circles, imperialism and militarism are extremely difficult issues. This is because they are seemingly irreconcilable with Okinawa’s postwar karate narratives, its notional philosophies, related marketing campaigns in tourism, and most of all, the recent endeavors to list Okinawa karate as an intangible cultural heritage with the UNESCO.

Therefore, the topic is avoided like the plague, all the more so since the Okinawan anti-war movement following the 1945 defeat. There is a conflict of conscience, the wish to repress memories of collaboration during the war years, the wish to disconnect karate from general daily life under the regime, the wish to present karate history as the sum of personal traditions of peace-loving Okinawans unaffected by the circumstances of the times, the wish – or is it pressure? – for harmony at all time, business or other private interests, the insular perception of schools and teachers which does not allow a differentiation of karate prior and after the 1945 defeat, the lack of communication from a bird’s eye view, the mixed ideologies of karate practitioners (everything from left to right, up and down), and so on.

The undeniable reality however is that imperialism and militarism where among the major formative forces behind the creation of karate in the early 20th century, at a time when karate was invented not as a self-defense, but to prepare young men for war, when karate was a conscription agers’ drill and education fueled by ideology. And the young men were receptive.

In short, karate’s actual history is often diametrically opposed to each and all narratives invented and propagated in postwar Okinawa. As a result, there is a certain imbalance in media and academic representations of Okinawa karate, a supra-dimensional contradiction, a skeleton in the closet.

It was therefore a refreshing novelty when in a 2021 paper about the movie “Ryūkyū no Fūbutsu,” the author pointed out various problems related to Okinawa karate and imperialism and militarism. Without getting in into the appalling details here, it is pointed out in the paper that “more careful surveys and research are required in the future.” As a first relativization, the author notes as follows.

“There is no first move in karate” (karate ni sente nashi) has been handed down as a proverb of the predecessors of Okinawa. It is a phrase that includes the meaning that karate is not about attacking first, but it is a technique to protect yourself and your loved ones. After experiencing the Battle of Okinawa, the significance of the aphorisms inherited from our predecessors has increased. I believe that today we can firmly maintain to emphasize the significance of karate as a “martial art of peace” (heiwa no bu).”

As you can see, karate ni sente nashi is cited as an aphorism and a peaceful philosophy of karate already before the era imperialism and militarism, which was just a chapter that had no relation to the real intention of karate whatsoever. Moreover, from that, the author stresses that the real meaning of karate is as a “martial art of peace” (heiwa no bu).”

As regards karate ni sente nashi, the phrase first appeared in 1914, in the article series Okinawa no bugi (Martial Arts of Okinawa), written by schoolteacher Funakoshi Gichin and based on the stories told by Asato Ankō. Here, Funakoshi tried himself as a karate historian and philosopher in an article series published and probably commissioned by the sole Okinawan newspaper at the time, the Ryūkyū Shinpō. The Ryūkyū Shinpō published various articles about what was euphemistically termed “education of conscription-winners” (chōhei tōsensha kyōiku) since August 1898. For this sort of education, the military assigned schoolteachers to prepare future conscripts. The Ryūkyū Shinpō also published lists of conscription dodgers. In short, the karate-related articles published by Ryūkyū Shinpō at the time were meant to support the official policies of the Japanese government.

I wonder if karate ni sente nashi was really a time-honored philosophy handed down by wise ancient masters with Prussian beards, or rather, if it was simply the daily necessity of an elementary school teacher who had do deal with boys and young men every day. As regards the schoolyard manners of boys and young men, they were not so much different in Okinawa than anywhere else, I guess. 10 years before Funakoshi tried himself as a karate historian and philosopher in the government-loyal Ryūkyū Shinpō, in the year of the outbreak of the Russo-Japanese War, at Shuri Middle School “the air was filled with war, and war talks,” and “not only the boys, but the adults too were in a dangerous mood. On the slightest occasion, fists attacked, and sticks were swung.” (Noma 1935) Particularly young men out of school were probably those found “at night in the vicinity of Tsuji,” where “gangs of thugs roamed around, of which it was said they were proficient in tekobushi and who were always ready to overwhelm unwary strangers.” Of course, tekobushi is an old name for karate.

It was the time when nations around the world accessed the resource of “young men” through conscription. The connection between school education and following military training is shown in the term “conscription society.” It is also worth mentioning that the government positioned the Young Men’s Corps between the school and military service since 1915, which were successful in Okinawa as an institution for education and (para)-military preparation of young men between 15 and 20.

More careful research is necessary in the future, but what Funakoshi said in 1914 was,

“Since ancient times, we have been instructed by the teaching of karate ni sente nashi, an expression that admonishes young men and boys from an educational point of view.”

He also said that

However, the first move is permissible in cases where the fate of the nation is at stake.

At this point, and from all I have studied so far about the matter, I guess karate can rightfully be an UNESCO ICH by all ethical standards. However, this only applies if it is limited to postwar karate.

© 2022, Andreas Quast. All rights reserved.