[This article was first published in: Quast, Andreas: Karate 1.0. 2013]

The first Western eyewitness accounts of Okinawa originate from Richard Wickham and William Adams (1564–1620).[1] The latter was later provided an estate and samurai status by shōgun Tokugawa Ieyasu, whom Adams served as a counselor.

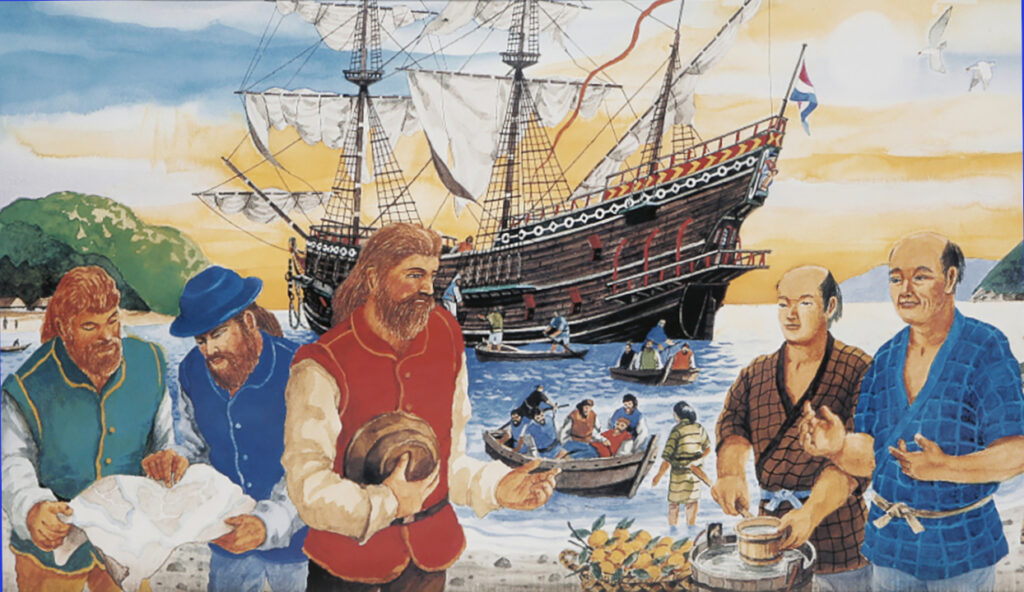

At the time both Wickham and Adams were working for the British factory of the East India Company, with headquarters in Hirado, Kyūshū. In August 1614 the factory bought a junk for 2,000 tael, naming it the Sea Adventure. Although another 2,312 tael were spent for repairs and outfit, she was said to not have been very seaworthy. Richard Wickham had to be persuaded to board as the head merchant, assisted by Edward Saris, and with William Adams as the pilot. Their first voyage was intended for Siam. The ship carried merchandise for barter and ₤ 1,250 for the purchase of Brazil wood, deerskin, raw silk, etc. from Siam. There were also several Japanese merchants on board, among them a certain Shobei. Adams set sails at Kawachi harbor, south of Hirado, on December 17th, 1614.[2] It was just when they had left the coastline behind,

when she was battered by a ferocious electric storm. The wild seas lashed at the recent repairs, loosening timbers and pouring water into the hold. For a day and a night the Japanese crew labored ‘to heave out and pumpe the water continually’, but the waters continued to rise. […] The attitude of their reckless English captain only increased their sense of terror. Adams appeared to be enjoying their predicament, urging them on in their endeavors and putting ‘the merchants and other idle passengers unto such a feare that they began to murmure and mutiny.’ As the winds howled and the waves crashed over the deck, the crew rebelled and told Adams that they would refuse to pump unless he headed immediately for the Ryūkyū Islands in the East China Sea. Adams had little option but to agree and, with heavy heart, he steered the vessel towards the subtropical island of Great Ryūkyū–today’s Okinawa–which lay some 500 miles to the south of Hirado.[3]

On their way they reached the port of Amami Ōshima on the 22nd. The local governor and others came aboard and assured their friendship, for which they were presented a lance. The governor recommended Wickham to go to Naha, being the main harbor on the island of Okinawa, where the king is resident.[4]

Richard Wickham, in a letter from December 23rd, 1614, wrote “and seing ourselves in extreme peril of death if that our leaks should increase never so little more, having now not more than 15 men, being the officers, who could stand upon their legs, the rest being either seasick or almost dead with labor, so that on the 20th, about 10 in the morning, we shaped our course for Okinawa Island […].”

In this way, in December 1614, five years after the invasion of the Satsuma and three years after the return of Ryūkyū king Shō Nei from captivity, Adams reached Naha, Okinawa:

The 27th in the morning we steered south for the harbor and came in about 10 o’clock, thanks to God, in safety, which harbor lies 9 leagues from the narrow passage which is some 18 or 30 leagues from the northern point of the island. This day was Tuesday, reasonable weather, much wind and sometimes little showers.[5]

There they met with “marvelous great friendship” and were given rice, meat, and turnips. Adams was permitted to bring his cargo ashore, while the Sea Adventure was to be repaired in the following five months.

During this time, Adams tried to make the best out of the involuntary situation and worked towards the establishment of a trading base. The local authorities, however, under instructions of the Satsuma fief, could not and would not comply with this request: Satsuma would neither allow interference in the trade relations between China and Ryūkyū, nor the possible suspicion of occasional Chinese visitors raised by the presence of a Japanese vessel in the port of Naha, even if it was led by Europeans. On the strategy implemented by the locals, Beillevaire wrote,

“If asked about their relations with Japan, the Ryūkyūans were supposed to answer that there were none, and that everything that might look Japanese came in fact from the Tokara Islands […]. The same explanation would continue to be in use with nineteenth-century western visitors.”[6]

The British, however, had already learned on Amami Ōshima that Ryūkyū recently had been “subordinated” to the daimyō of Satsuma:

“the inhabitants of these islands are descended from the race of the Chinese, wearing their hair long but tied up on the right side of the head, a peaceable and quiet people but in later years conquered by Lord Shimazu, King of Satsuma, so that now they are governed by the Japanese laws and customs […]”[7]

Satsuma tried everything to avoid that these kinds of information, with all its inherent meanings, were made available to third parties:

“This day the gentlemen of Shuri came to Naha to persuade me to go with our ship to Ōshima because in about 3 month a ship would come from China, and if we were here it would be an occasion to cause them to lose their trade which is the only means they live upon. But I answered that I was but on, I did not care where I died, either in here or in the sea […]”[8]

Meanwhile, Adam’s crew got out of hand, caused much trouble, and even rose up in arms. They demanded the payment of half the guerdon. Adams refused more than once, but under request of the merchants, who feared to lose their trade, he yielded at last. With their money the sailors then bought liquor and soon slashed at one another[9]:

“This day all our officers, mariners, and passengers rose up in arms to a fight with one another, but due to my great persuasion and Mr. Wikham and Sr. Edward Saris persuaded both sides and there was no bloodshed of no pity, thanks be to the Almighty God forever, Amen.”

Adams noted, that the Japanese merchant traveling on his ship, Shobei, with sixteen to twenty men entered the market all armed with swords, lances, halberds, and bows and arrows, “but with fair words I prevented our men, who were about 40 persons, from coming together.”[10] Wickham and Damian[11] also fell out and fought and were not reconciled till thirty days later.[12] In the following days, Adams tried to calm the parties, just like on March 9th, “but made not an end, still Shobe and his servants wearing their weapons in braving our men for peace.”[13] This continued until March 15th, when at last “the principal of Shuri came to the town of Naha to take up the quarrel between the merchants and the mariners, who made peace and a general agreement.”[14]

The situation eased, and two days later Adams, along with the merchants, was invited to a banquet by the Three Ministers (sanshikan). The following day he even received an invitation by the King in Shuri, who wanted to show him the capital and hold a banquet–a privilege which Basil Hall, two hundred years later, tried in vain to obtain–, however, Adams did not avail of doing so, because he had to make his ship seaworthy again.[15]

The mentioned dispute seemed to have been settled, when the ringleader in the night of the 26th of March again instigated unrest; the Japanese merchant Shobe found out about it, pitched on the troublemaker and slashed the man into pieces with his sword. “This day at night, he that had been the ringleader of the great mutiny being still foul of desperate parts, this night Mister Shobe killed him. This day fair weather, the wind northerly.”[16]

The misbehavior of his crew was a continual cause of trouble to Adams, and he had much difficulty in saving the lives of two of the men who had been condemned to death for stealing, etc. [17] After these incidents the hospitality of the local authorities was exhausted, and they ordered the departure of the Sea Adventure.

During his stay on Okinawa, Adams was constantly worrying on account of news brought by junks from Satsuma of the war between Ieyasu and Hideyori at Ōsaka. Although he had heard, on January 21, 1615, that the “Emperor had got the victory of which news I was glad,” yet a rumor reached him in May that “the emperor is likely to lose his country,” so he delayed a few days longer in order to have an interview with some officials from Satsuma who had brought the latest news.[18]

Adams’ logbook furthermore gives reason to believe that individual samurai probably having served under Toyotomi Hideyori sought refuge in Okinawa shortly before or during the ceasefire in January 1615: “The 21, being Saturday, here came a nobleman to Shuri who had fled from the wars in Ōsaka. His name was [blank]. This day I heard that the Emperor had got the victory, of which news I was glad to hear.”[19] Hence, apparently Japanese samurai, facing the looming defeat against the Tokugawa forces in mainland Japan, sought refuge in Okinawa, perhaps even with the knowledge and toleration of Satsuma.

Later, after Adams return to Japan, in late September 1615, he received a letter from Ieyasu, demanding his presence.

“Adams said that he thought the Emperor wished to hear about a fortress newly built in the Ryūkyū, where it was suspected that Hideyori might retire after his defeat.”[20]

Finally, Adams mentioned that he bought weapons on Ryūkyū,[21] namely four katana, an unknown number of wakizashi (but more than one as he used plural), and two yari for the total amount of “106 mas,” which today would correspond to an estimated 3.430 €, or 5.145 € considering deflation, which is a good price.

Ultimately this travel of the Sea Adventure costed more than 140 pounds and trading-wise it was a failure. The only person on board able to make profit from the situation was Richard Wickham, who had discovered that ambergris was considerably cheaper in Ryūkyū than elsewhere in Asia, and that it was traded for high prices in Japan: “here is great store of ambergris, the best that ever I saw and equal to that of Melinde, but is dear, at 90 or 80 tays a catty.” He bought two pound in the name of the trading post in Hirado, and two hundred sixty pounds for himself. One batch of his amount he later sold with 50% surcharge to the trading post in Hirado, another batch through an intermediary in Nagasaki, and a third batch went to Bantam, which earned him huge profits.

Adams collected a number of Ryūkyūan words and phrases which enabled him to “be polite to the officials of the island.” In this way he produced the first Western micro dictionary of the Ryūkyūan language, although “many of the words are unrecognizable.”[22]

Adams left Naha on the morning of May 20, reaching Kawachi harbor on June 10. One of the results of this voyage was the introduction of the sweet potato from Ryūkyū to Japan.[23] More than one hundred fifty years would pass until the next direct contact of western travelers with Ryūkyū.

Footnotes

[1] His Japanese name was Miura Anjin 三浦按針. Came to Japan as the navigator of the Dutch ship Liefde; was the first Englishman in Japan; gained the trust of Tokugawa Ieyasu; taught geometry, geography and shipbuilding; became diplomatic advisor; was awarded a fief in Sagami; and provided the inspiration for the novel “Shogun” by James Clavell.

[2] Purnell 1916: 167.

[3] Milton 2002: 248-249.

[4] “to goe for Nafe, being the cheefe harbor on the iland of Lequeo Grande, where the king is resident […]” Farrington, Anthony (ed.): The English Factory in Japan 1613-1623. Letters of Richard Wickham from Amami-Oshima and from Okinawa. William Adam’s voyage to the Ryukyu Islands in the Sea Adventure. The British Library: 273-74. 1991. In: Beillevaire 2000, Vol 1.

[5] Farrington 1991, 1051. In: Beillevaire 2000, Vol 1.

[6] Beillevaire 2000, I, p. 5.

[7] Farrington 1991, 326-27. In: Beillevaire 2000, Vol. 1.

[8] Farrington 1991, 1057. In: Beillevaire 2000, Vol. 1.

[9] Milton 2002, p. 250.

[10] Farrington 1991, 1057. In: Beillevaire 2000, Vol. 1.

[11] Damian Marin, a Portuguese who was afterwards made prisoner at Nagasaki by his fellow-countrymen for having served with the English. A special command for his release had to be obtained from leyasu by Adams.

[12] Purnell 1916: 168.

[13] Farrington 1991, 1057. In: Beillevaire 2000, Vol. 1.

[14] Farrington 1991, 1058. In: Beillevaire 2000, Vol. 1.

[15] Purnell 1916: 169.

[16] Farrington 1991, 1059. In: Beillevaire 2000, Vol. 1.

[17] Purnell 1916: 169.

[18] Purnell 1916: 169.

[19] Farrington 1991, 1053. In: Beillevaire 2000, Vol. 1. Purnell 1916: 196.

[20] Cocks, Vol. I: 49. Purnell 1916: 170.

[21] Purnell 1916: 219.

[22] Purnell 1916: 170.

[23] Purnell 1916: 169.

© 2022, Andreas Quast. All rights reserved.