Recently, I have written about the Ming Dynasty’s need for sulfur and horses to produce gunpowder and to pull cannons to the battlefield. Ryūkyū was able to supply both (Takara 1996: 46). According to the Minshu (Book of Fujian), the Chūzan Seikan, the Rekidai Hōan and others, trade articles during the whole Ming and Qing dynasties included swords and knife sharpeners (Wang 2010: 172. Majikina 1952: 72-73). Much of the Ryūkyūan swords and lances were from Japanese production (TIR-RKB 1. Heikin Shimatsu), but there were also blacksmiths and other craftsmen in Ryūkyū, and a particularly Ryūkyūan style can be seen in the ornamentations of the Japanese weapons and armors.

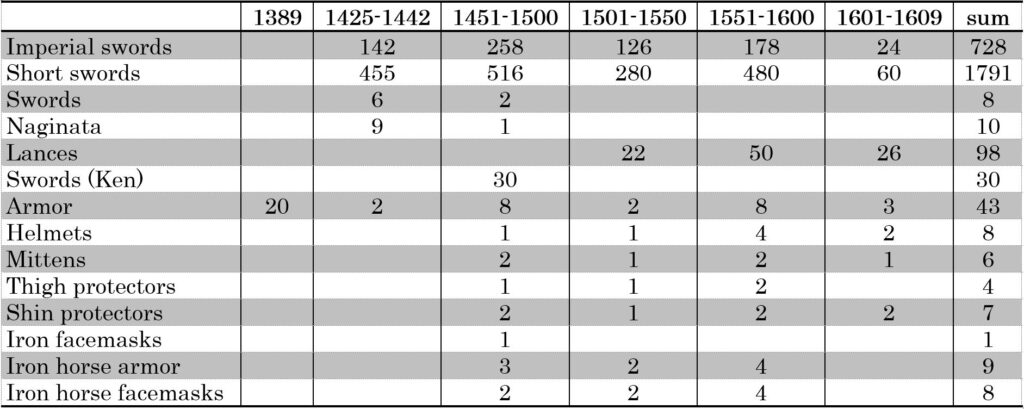

The number of swords and other weapons Ryūkyū officially exported to China during the Ming dynasty alone numbers in the thousands. The number of military articles in the following list amounts to 2,751 (Uezato 2010: 233, analyzed from the Rekidai Hōan).

Obviously Ryūkyū acted as an international arms dealer, using the Chinese tribute-trade system they had entered as a high-potential marketplace. The Palace Museum in Beijing still has a number of such swords and armors in its possession.

There were also cut and thrust weapons in Ryūkyū itself throughout the 15th to the 19th centuries, particularly among members of samurē class – i.e., most people in the urban centers of Shuri, Naha, Tomari, and Kume –, the nobility, and royalty, but also among commoners, as is shown in the following list of private property of crew members of a Ryūkyūan ship that sailed to China in the fall of 1864, the last six of which were commoners:

- 1 katana and 1 wakizashi: the supervisor Hokama Chikudun Pēchin.

- 1 katana: the chief interpreter Ōmine Pēchin.

- 1 wakizashi and 1 katana: the assistant writer Wakugawa Satonushi Pēchin.

- 1 wakizashi and 1 katana: the senior government official Takara Satonushi Pēchin.

- 1 wakizashi: the ship manager Takara Satonushi Pēchin.

- 1 wakizashi: the coxswain Ōmine Satonushi Pēchin.

- 1 wakizashi: Kinjō Chikudun.

- 1 wakizashi: Ishikawa Niya.

- 1 wakizashi: Kawakami Chikudun.

- 1 wakizashi: Chinen Niya.

- 1 wakizashi: Matsu Yamashiro.

- 1 wakizashi: Niwau Yamashiro.

(From: Asō 2007, referring to: Ryūkyū Shiryō (Vol. 2). In: Naha-shi Shi, Shiryō-hen Dai Ichi Maki 11. pp. 22-27. Naha-shi Kikakubu Bunka Shinkōka. Naha-shi Yakusho 1991.)

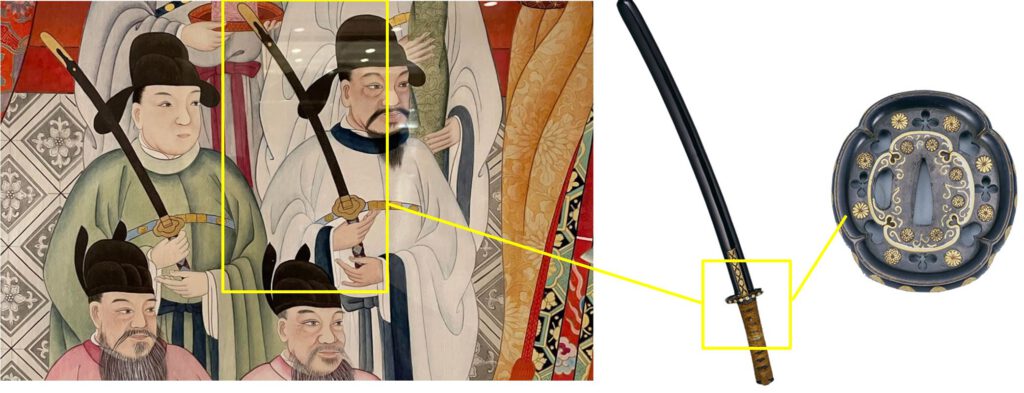

Below picture shows an excerpt of a copy of the restored drawing of King Shō Boku (1739-1794). It was produced by the Tokyo Art University Conservation and Restoration Japanese Painting Laboratory in 2020, and exhibited at the “Special Ryukyu Exhibition for the 50th Anniversary Okinawa’s Return” at Tokyo National Museum.

Middle and right seide: Sword and sword guard: © Naha City Museum of History.

The tsuba is probably a Ryūkyūan work. From the unique sword guards (tsuba), the black scabbards, and the overall uchigatana fashion, the swords in the illustration look quite like the sword called Jiganemaru. The blade of the Jiganemaru is estimated to be a production of the Nobukuni school from the Ōei era (1394-1428), so it is quite old.

According to the exhibition brochure, the “sword guard (tsuba) and seppa (washers) may have been produced in the royal workshop,” but it doesn’t detail which workshop that was (Official Pictorial Record, Tokyo National Museum 2022, p. 107). The fact that this sword has been handed down until today raises the question, namely: who were the craftsmen who maintained these articles in Ryūkyū for half a millenium? Was there a royal armorer in Okinawa?

Some parts of swords were cared for in a workshop called Magistracy for Shell-works (kaizuri bugyō 貝摺奉行), an office established after the Satsuma Invasion. In 1612, Hoeimō Pēchin Seiryō of the Mō Clan was appointed magistrate of this office and supervised craftsmen such as shell-works masters (kaizuri-shi), master painters (e-shi), cypress wood box makers (himono-shi), whetstone masters (tokimono-shi), and masters for unlacquered woodwork (kijibiki). The Magistracy for Shell-works decided on the form and design of lacquerware presented to the Chinese emperor, the Japanese shōgun, and the daimyō of Satsuma.

With the establishment of Okinawa Prefecture in 1879, the Magistracy for Shell-works was abolished, and the Okinawa Normal School was set up on the site in 1886.

Lacquerware continued to be manufactured by the private sector, and in 1912, an Okinawan Lacquerware Industry Association was formed, and articles were shipped to the mainland or sold as souvenirs.

After the Battle of Okinawa in 1945, production of lacquerware was revived and served as souvenirs for US soldiers and mainland tourists. After the Okinawa reversion, in 1980, “Ryukyu lacquerware” was designated a traditional handicraft by the Minister of International Trade and Industry.

Today, a memorial plaque of the Magistracy for Shell-works stands in Naha City, Shuri Tōnokura 1-4, right in front of Okinawa Prefectural University of the Arts. But this plaque vastly emphasizes the production of various articles made of seashells and lacquer, with only a marginal note about swords, and only because the scabbards were lacquered.

As pointed out by Watanabe, painters and lacquer masters who belonged to the Magistracy for Shell-works were “mostly lower-ranking samurē and produced paintings and lacquer works for the royal government, as well as articles presented as gifts to the Qing Dynasty of China, the military government of Japan (bakufu), and the Satsuma domain” (Watanabae 2014:149).

From the above descriptions it is evident that the Magistracy for Shell-works was a new office that appeared after 1609 and the designation magistracy (bugyō-sho) itself seems to point to Satsuma influence. In the making of weaponry, fittings (koshirae) are the parts of a sword other than the blade itself. It seems reasonable to assume that the Magistracy for Shell-works cared for lacquer works of the scabbards, inlay works, and the like. Just as in Japan, every part of the sword and its fittings – blade, cords and wrappings, scabbard, sword guards etc. – had its own master craftsmen. Therefore, there were probably different government offices responsible for different parts of the swords and armor. There were also differences in the government offices before and after 1609; some were renamed or abolished, or duties were shifted to other offices. Let’s dig just a little more.

The Shuri-Naha Dialect Dictionary of the University of the Ryukyus clearly states that the Magistracy for Shell-works was a royal government office which oversaw the production of tribute items. Since swords and armor were tribute items, the office could have supervised all craftsmen involved in swords and armor. However, in connection with the Magistracy for Shell-works, Watanabe only mentions paintings and lacquer works as gifts (=tribute items) produced for the Qing Dynasty, the military government of Japan (bakufu), and the Satsuma domain. In reality, though, swords were among the gifts presented to shōgun and to the Satsuma daimyō and others during almost every visit of Ryūkyūans until the end of the kingdom in the 1870s, and they also reached China under the Qing dynasty.

Matsuda wrote that the Magistracy for Shell-works directed and supervised the office work and craftsmen involved in the production of handiworks for royal family use as well as gifts (Matsuda 2001: 192, 215, with reference to Ryūkyū-koku Yuraiki (1713), I, 52–53), which allows for a broader definition of the articles produced and cared for by the Magistracy for Shell-works.

I guess it is complicated. Swords and fittings and parts thereof might have been supervised by various offices in dependence of the context, for instance, the context of tribute trade to China, the context of royal Ryūkyūan weaponry, the context of maintenance works etc. pp. For instance, as pointed out by Motobu Naoki Sensei, “Repairs that were not possible in Ryukyu could be done by taking the sword to Satsuma for repair. However, permission had to be obtained from the Zaiban [Satsuma Resident Commissioner] in Naha.” There was also a difference between categories such as private weapons, government-owned weapons, ceremonial weapons, and the like.

In fact, there was both a Royal Armory Management Bureau and a Department of Ceremonial Weaponry. I will cover these shortly in a future article.

Sources (excerpt)

- Matsuda Mitsugu: The Government of the Kingdom of Ryukyu, 1609-1872. Front University of Hawaii, 1967.

- Shuri-Naha Hōgen Dētabēsu (Database for the Dialects of Shuri and Naha). Ryūkyū Gengo Kenkyū Sentā (Study Center for the Ryūkyū Language). 首里・那覇方言音声データベース。琉球言語研究センター。

- Watanabe Miki: 04 Kaidai to Kōsatsu – ‘Ryūkyū Kōekikō Zubyōbu’ Kō (04 Synopsis and Consideration – Report on the Investigation Into the Folding Screen Bearing a Map of the Ryukyu Trading Harbor). Nihon Kinsei Seikatsu Ebiki: Amami Okinawa-hen. 2014, p. 149. 渡辺美季:04 解題と考察 – 「琉球交易港図屏風」考. 日本近世生活絵引、奄美・沖縄編。2014、p. 149。

- Quast, Andreas: Karate 1.0. 2013.

- Kaizuri bugyō-sho described by the Naha City Museum of History.

- Asō Shinichi: Ryūkyū ni okeru Satsuma-han no Bugu Tōseirei. In: Okinawa Bunka. Bd. 41, Nr. 2, 102, May 2007. pp. 43-68. Okinawa Bunka Kyōkai, Naha 2007. 麻生伸一:琉球における薩摩藩の武具統制令について。沖縄文化。第41巻2号102、 2007年5月。沖縄文化協会。

- Official Pictorial Record of the Special Exhibition “Ryukyu” for the 50th anniversary of the Return of Okinawa. Tokyo National Museum / Kyushu National Museum / NHK / Yomiuri Shimbun, 2022, p. 107.

© 2022, Andreas Quast. All rights reserved.