In early modern Okinawa, that is the era between 1879 and 1945, there was a system called “Customs Improvement Movement.” It was a part of the assimilation policy and included the revision and abolition of Okinawan customs that were considered a hindrance to modernization.

The customs improvement movement consisted of two elements, namely 1. Assimilation and 2. Modernization. Some of the targeted customs were smoothly abolished, while the abolition of other customs failed. For example, the prohibition of going barefoot or the cleaning of roads were considered modern and rational, and not as a forced assimilation, so they were not rejected by the Okinawan people. Tattooing, on the other hand, was one of the few customs that has been successfully revised and abolished, but its abolition too has an element of modernity and rationality to it and cannot be simply considered an assimilation policy, so people understood it. On the other hand, if an abolition of customs was considered unneccesary or unwanted by the people, the rejected it.

Itani argues that early modern assimilation policy in Okinawa has a too short range and that rationalization and modernization of daily life actually has a longer history, ranging from the era of the royal government even to the present. Some of the customs, such as the simplification of important ceremonial occasions in family relationships (such as coming-of-age, wedding, funeral, ancestor worship) or rituals, still in the 21st century remain issues for the improvement of village societies. Therefore, Itani promotes the use of a broader historical range that goes beyond the relatively short period of the customs improvement movement.

As an example, some customs, which were temporarily cut off due to suppression, were revived after 1945 if the people really wanted them. Customs that have not been revived after 1945, on the other hand, had lost the social function that once supported them and consequently became obsolete. This includes customs such as “mō-ashibi” and “uma-dema,” whose premise was “marriage inside a village” and which are limited to the topic of marriage.

NOTE: Sexuality and marriage of young men and women in rural areas was often associated to mōashibi, or enjoying a night in the fields with singing and dancing etc. There were few marriages outside one’s own village, but in that case, alcohol or otherwise the alcohol expense had to be presented to the young men in the woman’s village. This is called “umadema.”

Five educational functions accompanied the occasion of mōashibi and can be ordered as follows:

- the function of handing down songs and dances such as mēkata,

- the function as an occasion for creative activities,

- the function of handing down traditional physical education of the region,

- the function of creating a circle of friends, and

- the recreational function that creates vitality for tomorrow’s labor.

Number 3, the transmission of traditional physical education, included wrestling (called mutu), a kickboxing-like kind of grappling (called tose), karate, sumo, and bojutsu.

Doubts remain however as to how well the leaders of the customs improvement movement understood their own culture. A point to keep in mind here is that the customs improvement movement was not organized by national or prefectural governments, but by Okinawan young men’s associations (seinenkai) and customs improvement associations, that is, by people somewhere between 16 and 25 years of age.

While customs such as various forms of martial arts had been handed down by the Okinawan young men’s associations, other customs where not. For instance, from the royal government era to the postwar period, there were customs such as “yuta-kōyā” that are still today subject to revision and abolition. The understanding of Okinawan culture by the leaders who worked on the reform and abolition of customs was superficial, proof of which is that the movement did not reach the deep religious nature of the spiritual life of the people.

NOTE: Yuta-kōyā is the act of buying the services of a yuta. This usually requires the judgment of two or three yuta. The client is willing to pay a considerable amount of money to the yuta. There is a long-standing saying in Okinawa, called “half a doctor, half a yuta.” There is also the saying that “men buy prostitutes, women buy yuta.”

For people in the prewar era, the difference between the customary laws of the villages and modern law was not unambiguously clear. In the life of the village (shima) we see the fact that the customary laws were like a melting pot in which tatemae (one’s official opinion) and honne (one’s real opinion), legal regulations and loopholes were mixed together.

In the above sense, Tanigawa Ken’ichi (1972) identified the characteristics of Okinawa as,

“Everything is undifferentiated in Okinawa, and the historical society of Okinawa reflects light at various angles like polyhedral crystals.”

NOTE: The above is part of a study into youth groups in Okinawa and mainly based on: Itani Yasuhiko: Social education as an Okinawan custom seen in the “penalty tag” system of the Customary Laws of Southern Island Villages (Nantō Mura Neihō). Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor in Education. Waseda University Number: New 7911. Waseda University 2018, pp. 153-154.

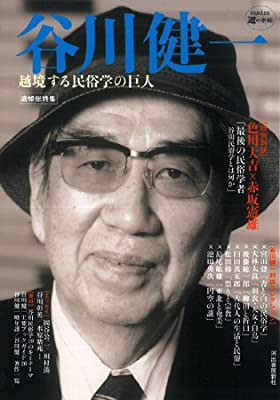

BTW, since there is almost no material on Tanigawa available in English, I will provide some here.

Tanigawa Ken’ichi (1921-2013) was one of the most important cultural anthropologists in Japan, especially with regard to historical place-name studies, folklore, and Japanese literature.

After attending middle school in Kumamoto, he majored in French literature at the Imperial University of Tokyo.

Tanigawa collected information about the way of life and culture of the lower social classes, traditions, rites and legends that have to do with the coast as a buffer zone between sea and land, between ideas of the afterlife and this world. His specialty are place names. Numerous publications appeared from 1957, initially by Heibonsha. In the 1960s he got into a scholarly dispute with Origuchi Shinobu and Yanagita Kunio (1875–1962).

His “Collection of the Historical Biographies of the Simple People” (published 1973) comprises 20 volumes, the “Compendium of Japanese Folk Customs” (1986) comprises of 14 volumes. In 1981, the city of Kawasaki set up an “Institute for Research into Japanese Place Names,” of which he became the director and from which he received an award in 2008. From 1987 to 1996 he taught at the Kinki University of Osaka, where he directed the anthropological institute.

He has also written novels such as “Umi no Murubushi” which was made into a drama on NHK in 1988 with appearances by Ogata Ken, Ishida Yuriko, and Orimoto Junkichi.

He is highly praised for his achievement of the “Theory of the Development of Literature in the Southern Islands,” based on songs from Okinawa and Kagoshima as a source of Japanese literature. He has received several academic prizes for research achievements, including one in 2001 for his Tanka collection. In 2007 he became a “Bunka Kōrōsha” (“person with special cultural achievements; it is an honorary title combined with a government annuity).

Tanigawa Ken’ichi is the eldest of the Tanigawa brothers, including the poet Tanigawa Gan, the oriental historian Tanigawa Michio, and Yoshida Kimihiko (formerly: Tanigawa Kimihiko), the founder of The Editors’ School of Japan. His eldest son is Tanigawa Akio, an archaeologist and professor at Waseda University.

© 2020, Andreas Quast. All rights reserved.