There were some questions online regarding the previous short article “Fujian Southern Boxing (1).” So I’d like to add some more info by Wen Xinhui (Associate Professor, Graduate School of Physical Education, Jimei University, China), translated below.

The historical source of Fujian Southern Boxing

Chinese martial arts were originally created by soldiers. Among them, the history of Fujian Southern Boxing is roughly divided into four elements.

• First, the history (culture) of Fujian is based on the Baiyue culture (generic term for southern ethnic groups) and formed under influence of the propagation of Zhongyuan culture (the Central Plain, i.e. the middle and lower regions of the Yellow river, including Henan, western Shandong, southern Shanxi and Hebei).

• Second, in the war against the Japanese pirates (actually, Japanese, Korean, and Chinese ethnicities) of the Middle Ages, from the Yuan dynasty (1279-1368) until the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), exchanges with soldiers took place and Fujian Southern Boxing was born. As kata that influenced the emergence of Fujian Southern Boxing, the Jixiao Xinshu (1560) includes the description of the “Staff Fencing of the Yu-Family” (yujia-gun) at the Shaolin Temple in Henan province in central China. Those kata were handed down by Yu Dayou (1503-1579), who contributed to the victory of the war against the Japanese pirates of the Middle Ages.

• The third is due to the history and incidents after the anti-Qing movement called “Oppose the Qing and restore the Ming,” which led to a rapid spread of Fujian Southern Boxing.

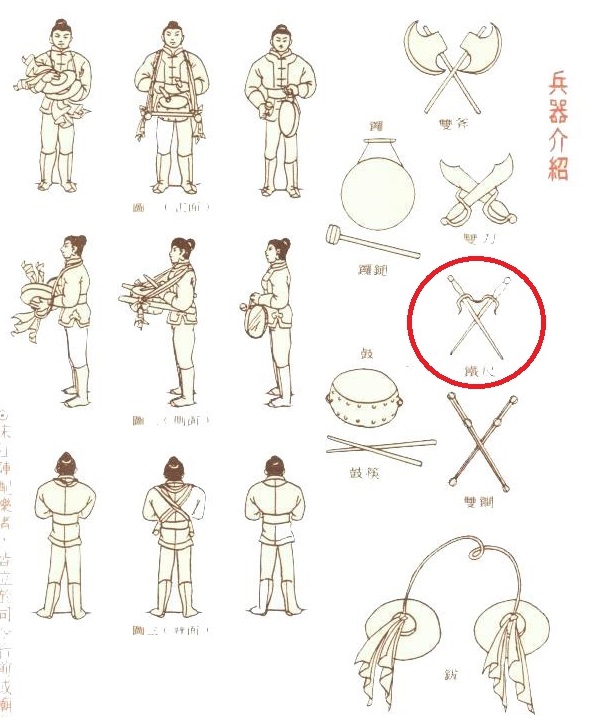

• Fourth, Fujian Southern Boxing was transmitted along with folk customs and folk art. Chinese martial arts literature related to this is found from the Song dynasty (960-1279) to the Ming dynasty (1368-1644). For example, there is the “Gaojia” (high armor opera) in Quanzhou, and the “Gejia” (dagger-axe & armor opera), dances with a history leading back to the Tang dynasty (618-907). Lion Dance is divided into three categories depending on its region: In Beijing it is the golden lion, in Guangdong the white lion, and in Fujian the blue lion. The blue lion stands for “Oppose the Qing and restore the Ming” and it represents combatting the army of the Qing dynasty (1644-1912). And the lion dance in Fujian is called by names such as “Slaughtering-lion troupe,” or “Song Jiang battle array.”

Under the dominance of the Imperial rule in the Song dynasty (960-1279), the administrative units of counties and below had no power but instead were governed by “clans” and private groups on village basis, and martial arts were developed and preserved in smaller units.

There is a type of karate kata called “Chintō,” and the origin of its pronunciation is considered to be found in the term “Chin 陣,” as in “village militia” or “Song Jiang battle array.” Such “Chin” were part of China’s administrative division at that time. Originally, the villages of Fujian Province had an organization called “Song Jiang battle array” (as in Song Jiang, a principal of the 108 (!!!) heroes of the novel ‘Water Margin’). These village organizations played an active role during festivals, not only in martial arts, but also in folk performing arts such as lion dance. The troupe leaders called tou 頭 (Jp. kashira) perform a kata called Zhentou (Jp. Chintō 陣頭), i.e. “Leader of the Battle Array.”

This kata of “Chintō” is not a set kata, but a “kata the troupe leader is good at.” In fact, there is also a kata called Zhentou (Jp. Chintō 朕頭) in Five-Ancestors-Boxing. If you follow the stream to the source, karate’s “Chintō” may be connected to these somewhere in time.

The Historical Formation of Fujian Southern Boxing

It was the success of Zheng Chenggong (1624–1662; also known as Koxinga) that played an active role in the anti-Qing movement to “oppose the Qing and restore the Ming.” Zheng was based in Xiamen and Jinmen islands off the coast of Fujian, where many martial artists gathered under him. Many of those who were in Fujian Province at that time fought against the new Qing government, and it can be inferred that martial arts also developed at that time.

A clear record of the historical formation of Fujian Southern Shaolin Boxing is the entry on “Wu Qi Shi (Mr. Wu Qi)” in the “Miscellaneous Jottings on the Archipelago” (Haidao yizhi, 1806). This document refers to Indonesia. When attacked by the Dutch, the people of an island (in Indonesia) became allies and brothers with Wu Qi. In addition, when attacked by pirates, they were able to regain the ship. It is said that Wu Qi had practiced the martial arts in all countries of Southeast Asia and was respected as a great hero. It was recorded that Wu Qi taught them all the various skills of wielding the spear and the sword etc., regardless of being male or female, from ten years or older. Those teachings had many names, such as Great-Ancestor-Boxing, Arhat (Monk) Boxing, Ape Boxing, and Crane Boxing.

The Xiaodaohui (Dagger Society, anti-Qing secret society who mounted an unsuccessful rebellion in 1855), as well as the Chinese boxer movement (Giwadan), which spread from the late Qing dynasty to the early Chinese revolution, are related to the development of Fujian Southern Boxing. In modern times, Chinese martial arts specialize in competition.

Blogger’s Addendum

Professor Wen also provides an interesting interpretation of the neijia which is usually technically classified as internal martial arts of a Taoistic nature and origin:

Fujian Southern Boxing is a neijia (inner family) boxing, that is,

Wen Xinhui

it follows the premise “to gain the initiative by striking first.”

Bilbio:

Wen Xinhui (Associate Professor, Graduate School of Physical Education, Jimei University, China): A Study on the History and Culture of Fujian Southern Boxing, as well as its Domestic and Foreign Propagation. On example of “Five-Ancestors-Boxing,” “Southern Shaolin Five-Ancestors Crane-Sun Boxing,” “Shōtōkan-ryū,” and “Gōjū-ryū.” In: Ryūkyū Karate no Rūtsu wo saguru Jigyō – Chōsa Kenkyū Hōkokusho (Research and Study Report – Project to Explore the Roots of Ryūkyū Karate). Urasoe City Board of Education, March 2015. Pp. 49-51.

© 2020, Andreas Quast. All rights reserved.