Japanese ceramic artist Hayashi Kyōsuke 林恭助 is one of the few people worldwide who succeeded in recreating what is called a Yōhen Tenmoku teabowl (Yōhen Tenmoku Chawan 曜變天目茶碗) in Japan, or Jian teabowl (Jian zhan 建盞) in China. This refers to a specific kind of teabowl that have been fired roughly 800 years ago during the southern Song dynasty (1127–1279) in the kilns of what is now Fujian province: While originally large quantities of teabowls were produced at those kilns, within the baking process a very few of them gained star-like glowing patterns on the surface which allow for the designation as Yōhen Tenmoku teabowl.

There are different categories of Tenmoku teabowls from the kilns in present-day Fujian Province back in the Song dynasty. In Japan, within these categories – and in fact within all teabowls – the Yōhen Tenmoku are considered to be the ones of supreme quality. They are characterized, among others, by patterns of starburst sparkles embedded in a dark blue glaze.

As regards terminology, Yōhen – written 曜變 or 耀變 – literally means as much as “gloriously transforming…” It seems to refer the calaidoscopic effects of glistening iridescent sparkles, colors and surface structure under changing light. However, usually it is translated as “changed by the fire,“ referring to the effects of the baking process on the glaze that takes place in the kiln. Sometimes it is simply translated as “spotted” or “speckled.”

Tenmoku is the Japanese pronunciation of Mount Tianmu (lit. Heaven’s Eye), located on the border of Zhejiang province and Anhui, China. Mount Tianmu lent its name to the teabowls which became known as Tenmoku in Japan.

So, as a somewhat adequate working solution, Yōhen Tenmoku Chawan might well be translated as “gloriously sparkling Tenmoku-style teabowl.”

Hitherto only three completely intact specimens of “gloriously sparkling Tenmoku-style teabowls” are known to exist in the whole world. All these three are located in Japan, and all these three are designated a National Treasure. The three current “gloriously sparkling Tenmoku-style teabowls” belong to:

- Seikadō Bunko Art Museum in Tōkyō.

- Fujita Art Museum in Ōsaka.

- Ryūkō-in subtemple of the Daitokuji Temple in Kyōto.

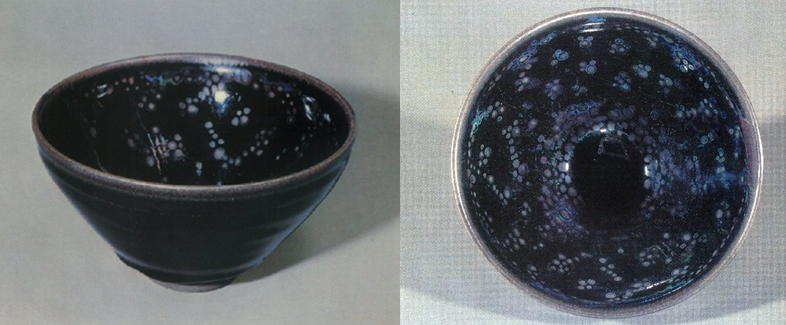

Crystalline patterns appear spontaneously within the baking process and produce the distinctive starburst sprinkles. In most cases these sprinkles appear mainly on the interior of the bowl, such as in case of the specimen of the Seikadō Bunko Art Museum, which is considered to be of the highest quality among the “gloriously sparkling Tenmoku-style teabowls.” However, in case of the Fujita Museum specimen the sparkles are on the exterior surface of the bowl, which is a unique feature and makes it absolutely gorgeous.

- Seikadō Bunko Art Museum in Tōkyō.

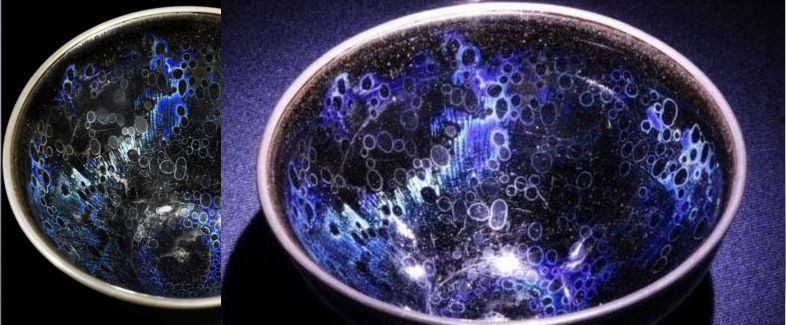

“Gloriously sparkling Tenmoku-style teabowl” (designated a National Treasure of Japan) of Seikadō Bunko Art Museum in Tōkyō.

2. Fujita Art Museum in Ōsaka

“Gloriously sparkling Tenmoku-style teabowl” (designated a National Treasure of Japan) of Fujita Art Museum in Ōsaka.

3. Ryūkō-in subtemple of the Daitokuji Temple in Kyōto

“Gloriously sparkling Tenmoku-style teabowl” (designated a National Treasure of Japan) of Ryūkō-in subtemple of the Daitokuji Temple in Kyōto.

A fourth Yōhen Tenmoku teabowl was discovered in Hangzhou in Zhejiang Province, China in 2009. However, it is broken to various pieces.

“Gloriously sparkling Tenmoku-style teabowl” discovered in Hangzhou in Zhejiang Province, China in 2009.

Well, this rare porcelain manufacturing technology of the Song Dynasty has been long lost in China itself. The reason for this is that, while ceramic-making methods reached their all-time pinnacle 800 years ago during the Song Dynasty, the technology fell in disuse soon afterwards and finally was lost completely. It is therefore little surprising that, when in 2007 earlier mentioned ceramic artist Hayashi presented a replicated “gloriously sparkling Tenmoku-style teabowl” to Chinese ceramic experts in Beijing, they greatly admired it and and commended Hayashi’s reproduction. At that time no one in China was able to recreate such a teabowl.

Ceramic artist Nagae Sōkichi 長江惣吉 from Seto City in Aichi Prefecture also succeeded in reproducing replica of a “gloriously sparkling Tenmoku-style teabowl,” and his replica is considered to come as close as possible to the originals. Actually, Nagae produced the astonishing number of 20,000 teabowls, of which only 4 or 5 achieved the quality necessary to actually deserve the name “replica” of a “gloriously sparkling Tenmoku-style teabowl.” BTW, teabowls deemed unworthy are simply destroyed – there is no such thing as a second quality here. To be exact, from among the batch size of 20,000 teabowls produced by Mr. Nagae, only 0.025% reached the necessary quality characteritics. The remaining 19,995 “unworthy” teabowls were all scrapped. As a matter of fact, the reproduction of “gloriously sparkling Tenmoku-style teabowl” is considered very difficult by all experts unisono. Translated to the practice of karate kata, the above would mean that 99.975% of your attempts to perform a perfect kata would be failures.

Considering the above, you may imagine the complete perplexity among experts when at the end of December 2016 the TV Tokyo show “Better Fortune! The Appraisal Team for Anything” hunted out a teabowl. One of the show’s art connoisseurs, Nakajima Seinosuke, judged the teabowl to be a genuine “gloriously sparkling Tenmoku-style teabowl” of national treasure-class. The teabowl was then estimated to be worth around 25 million Japanese Yen (approx. US $ 217,123 or € 202,952). Watch the appraisal here, or the full show here.

Since that day, this has become news all over the world.

The teabowl owner, who runs a ramen noodle-house in Tokushima, provided a convenient historical narrative: his great-grandfather found the teabowl when he worked as a carpenter building the residence of a descendant of Miyoshi Nagayoshi (1522–1564), a powerful warlord during the Japanese Age of Civil War.

WOW!

However, meanwhile, earlier mentioned professional ceramic artist Nagae Sōkichi remonstrated the sensational discovery as being a low-quality Chinese imitation, such as are currently produced as souvenirs etc. in the kilns of China. “If you call this TV show teabowl a ‘gloriously sparkling Tenmoku-style teabowl’, then there are hundreds of thousands of ‘gloriously sparkling Tenmoku-style teabowls’ in this world,”says Nagae. Actually, just two days ago from now, on January 27, 2017, Mr. Nagae also protested the appraisal via a YouTube video in English.

Nagae is a 9th generation in a family line of ceramic artists who have attempted the perfect reproduction of “gloriously sparkling Tenmoku-style teabowls” throughout the last two generations of father and son, over 70 years. Among others, Nagae pointed out that the color used for the TV show teabowl is a ‘spinel pigment’ color that was developed in Europe and only since the 18th century.

Asked about his impression of the appraisal of the teabowl on TV Tokyo’s show, Mr. Nagae explained:

“When I watched the program, at the moment when the tea bowl was appraised ‘gloriously sparkling Tenmoku-style teabowl,’ I was surprised. This is because it was clearly a souvenir-quality imitation such as is currently mass produced in kilns of China. I thought that this was certainly a joke.

Actually I thought to myself, ‘Today is not April Fool’s Day, or is it?’

However, I became speechless when I heard the appraisal that ‘Just as the gloriously sparkling Tenmoku-style teabowls that are designated National Treasures [in Japan right now], this teabowl was certainly baked in the kilns of the Song Dynasty!’ ”

Mr. Nagae continued:

“Even if a common person sees is, the difference between the teabowl presented in the TV show and the ‘gloriously sparkling Tenmoku-style teabowls’ that are designated National Treasures will be obvious. Both are totally different things. Looking at the image of a deer, would anyone believe that it is a horse? …

The teabowl presented in the TV show is such a low-level imitation that it does not even compare to imitations. Actually it is reminiscent of a kindergarten work. It does not even reach the level of a ‘forgery’.”

Journalists inquired about the newly discovered TV show teabowl with several art museums and antique art dealers, but in all cases they answered “It is nothing compared to the original ‘gloriously sparkling Tenmoku-style teabowls’ (that are National Treasures)…”

Morever, a survey planned with the teabowl’s owner for registration as a cultural property with the Tokushima prefectural government was suspended by January 23. It is said that this was caused by the owner who now wishes to “refrain from providing any information to the outside at all.”

Why does this remind me of certain karate kata that appeared out of nowhere, that are allegedly centuries old, but noone seems to have any clear information or even the willingness to inform the millions of karate fans, practitioners, sensei, and trainers and sportlers around the world just about how these specific kata reached you, your eminence?

I hope they are not modern forgeries from Fujian or elsewhere!!!

Anyway, the above topic of the teabowl was recently cited as an analogy with karate on the Motobu-ryū Blog in Japanese. I will continue here and provide a translation of the karate part (with kind permission of Motobu Naoki Shihan of the Motobu-ryū):

I think the traditions of martial arts (budō) do somehow resemble the above circumstances (of the teabowl). Following the Meiji Restoration (since 1868), many martial arts schools disappeared since they were no longer needed due to Japan’s Westernization movement. Furthermore, even after the Pacific War (1941–45) martial arts schools experienced a time of agony.

Karate’s fate was similar, but in its case—because on its inside a movement of self-denial developed under the outward pretense of “modernization”—many old-school kata and kumite techniques have been lost or were changed.

In karate magazines of about 1975-1985, karate people from various schools loudly clamored for a “modernisation of karate,” while the same people today refer to themselves as “karate of the traditional factions” (dentō-ha karate). So when I reread the magazines of those days this astonished me a bit.

In the Motobu-ryū, Sōke [Motobu Chōsei] in the past also received “advice” from persons of other schools, such as “Practicing a simple kata like Naihanchi is worthless (from the point of view of competition),” or “How about you change it to be more dynamic?” However, seeing the current reappraisal of Naihanchi, I will continue to believe it was good without changes.

…

Techniques lost once are not easy to reproduce. Unfortunately, unlike pottery which materially remains after 800 years, even if karate would be reproduced, who could assert that they are the same original intangible techniques of martial arts as they once were?

Therefore, I think that it is important that karate is being inherited uninterruptedly, and without being swept away by the fashions of the times.

Otherwise it might just be some kungfu in white dogi from a mass-production Karate souvenir shop…

© 2017 – 2023, Andreas Quast. All rights reserved.