ithin the unpopular history of an island’s people, there are countless historical facts on treason and betrayal in Okinawa on account of base motives. There are always two sides to a story, and least you’re an attourney general, one’s personal perspective is often the sole determinating factor towards the good or the bad of the person. It’s kind of funny that opinions and historical descriptions related to Okinawa often are given in two completely contrary opinions. Just like in karate.

ithin the unpopular history of an island’s people, there are countless historical facts on treason and betrayal in Okinawa on account of base motives. There are always two sides to a story, and least you’re an attourney general, one’s personal perspective is often the sole determinating factor towards the good or the bad of the person. It’s kind of funny that opinions and historical descriptions related to Okinawa often are given in two completely contrary opinions. Just like in karate.

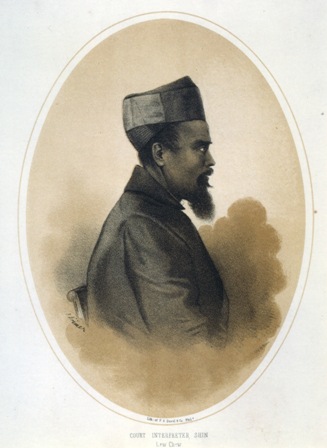

One such story is that of interpreter Makishi Chōchō (1818-62). Makishi belonged to the Shuri shizoku in the closing days of the Ryūkyu kingdom. First he went by the name of Itarashiki, then Ōwan, and later called himself Makishi. Proficient in the Chinese and English languages, he became an interpreter. Mentioned frequently as an English interpreter in Commodore Perry’s narrative of his expedition for opening Japan, the looks of Makishi were preserved to posterity in the narrative.

Matthew C. Perry, Francis L. Hawks: Narrative of The Expedition of an American Squadron to the China Seas and Japan. Washington, 1856.

And, accompanying such enigmatic figures as Asato Ankō, he received instruction in Jigen-ryū by Matsumura Sōkon (OKKJ 2008: 107).

Up until here, popular priming would strongly suggest he was “a good one”.

With the progress of cultural enlightenment and the anti-Tokugawa movement in Japan during the closing days of the Tokugawa shogunate, Makishi had been secretly deployed by the Satsuma xdaimyō Shimazu Nariakira. In 1857, while having been born as a rankless commoner, he was promoted to “keeper of the minutes” (hichō 日帳) within the Omote Jūgo-nin, i.e. the Council of Fifteen, an influential group of officials comprised of the heads of the major divisions of the Okinawan royal government, ranking immediately below the Council of Three, i.e. the Sanshikan.

Makishi, in his role as a secret aide to Nariakira, in Kagoshima defamed the conservative Sanshikan Zakimi Seifu, and later, during the period of election of duties, Makishi commenced rumours of bribery. The simple reason for this was that the conservative faction within the royal government of Shuri dismissed Nariakira’s modern political route and his foreign policy of purchasing French warships. Zakimi, belonging to this conservative faction, was finally banished under suspicion of being about to plot the deposition of the monarch. With no clear evidence existing, the trial was conducted solely upon Makishi’s diclosures. To put it bluntly: he lied heaven and earth.

After the demise of Nariakira in 1858, however, and just as in all the countless other stories on treason and betrayal in Okinawa, things came to light and Makishi, together with the royal treasurer Onga Chōkō and the Sanshikan Oroku Ryōchū were arrested and imprisoned as ringleaders of the bribery scandal known today as the Makishi-Onga Incident.

In consequence, Makishi was banished to Kumejima for 10 years, Oroku was put in temple arrest in the Shōtai-ji on Iejima for 500 days, and Onga was banished to Kumejima for 6 years.

Onga died in prison in March 1860. Makishi was bailed out by the Satsuma-han in order to work for them as an English teacher. En route to Kagoshima, however, it is said he threw himself to death offshore Iheya Island.

But maybe that is just a lie.

© 2012 – 2018, Andreas Quast. All rights reserved.